News of the Week: this will be the final 2022 film roundup installment…until, maybe, I watch the fifteen Oscar nominated short films. Next up is a 2022 State of the Film Union, then back to normal programming.

Watch Now

No Bears (2022, Jafar Panahi, Iran) is Panahi’s fifth film since receiving his twenty-year ban on filmmaking in 2010. He was also sentenced to six years in prison in the same verdict, which the Islamic Revolutionary Court decided to enforce last July after Panahi inquired with the prosecutors' office about fellow Persian filmmakers Mohammad Rasoulof and Mostafa Aleahmad, who were imprisoned three days earlier. Panahi and Rasoulof were arrested together in 2010 on charges of “propaganda against the system.” But in reality, the delayed enforcement was likely a response to the Biennale's announcement that his latest film, No Bears, was in competition. The film won the Special Jury Prize while Panahi was two months into his six-year prison sentence. (Panahi was released a week ago after announcing his intention to start a hunger strike.)

Although he was officially under house arrest from 2010 to 2022, he was allowed to leave his home but couldn't travel outside of Iran. During this time, he clandestinely made docu-fictions that elaborated on the themes of his previous films, which became even more appropriately subversive under the circumstances. In No Bears, Panahi plays himself, a country-bound filmmaker staying in a small Iranian village on the border with Turkey. Across the line, his crew is shooting a feature film that he's directing via shotty online video connections.

His own struggle with this distance is complicated when he becomes involved in a village dispute after taking a photo of a young couple together, one of whom has been promised to another man in the village. As in a Farhadi film, the dispute gradually escalates until the entire male population is shouting at each other and religious ceremonies are needed to settle things. Panahi, at the center, claims not to have the photograph, which forces him to take part in the eccentric village rituals. Not dissimilar to his own life as a modern filmmaker under the strict guidelines of an Islamic state, he's always on the border of escape, which becomes literal and physical in No Bears as he contemplates crossing the border under threat of imprisonment—which he prophetically received irl two months after filming ended and two months before its Venice premiere.

While he’s dealing with this village dispute, he’s also struggling to direct a film about an Iranian couple in Turkey attempting to get forged, or at least belonging to real people, passports. There are so many intersecting lines between reality and fiction that it’s hard to believe the cast and crew in the Turkish city are a group of professional filmmakers rather than a scrappy underground film unit that Panahi is endangering. The female lead in the film, Mina Kavani, who has an excellent monologue during the climax, was exiled to France, a country she acquired citizenship in 2010, after starring in a film (Red Rose, 2014) with nudity. (Kavani read a statement from Panahi at the New York Film Festival premiere of No Bears.) Kavani and Panahi emphasize the reality of artistic freedoms in both filmmaking and public statements, which heightens the docu-reality of a supposedly fictional film like No Bears.

The film, like Panahi’s first film under house arrest, This Is Not a Film, is excellent in its command of what filmmaking, and by extension art in general, means to an individual, a viewer, a country, an international community… like no other film or filmmaker working today can do.

No Bears is still in its minuscule theatrical release in the USA. Hopefully it will be available to stream soon.

Save for Later

White Noise (2022, Noah Baumbach, USA/UK) is Baumbach’s unusual adaptation of a novel that also, unusually, isn't set in NY or is co-written by Greta Gerwig, who stars in the film alongside Adam Driver. Gerwig and Driver seem to be the only links between Baumbach's contemporary comedies and Don DeLillo's postmodernist winner of the 1985 National Book Award winner. The two leading stars form the Gladneys, a married couple with four children from three different nuptial unions—Babette (Gerwig) is Jack's (Driver) fourth wife. Jack, a professor of Hitler studies, the best in the country, and Babette, a housewife with a pill problem, have a mutually reinforcing fear of death that is exacerbated by an "Airborne Toxic Event" that forces the entire suburban community to evacuate.

While small details are liberally changed from the source, it's mostly faithful. It begins with a Reagan-era community and academic satire. Then a toxic airborne incident forces the family to evacuate, which is the comedic high point of the film. Jack unknowingly stands in the toxic air for over a minute, so he must confront death directly and intimately, rather than through classroom Hitler slides. During this time, Jack becomes aware of Babette's drug use, which he confronts in the second half of the film.

The problem many have with the film is its inability to fully translate the satire of a then-contemporary novel into a period-piece film (as well as adapting a postmodern story, which comes across visually as silly and insincere). Since arriving at Netflix, Baumbach's films have expanded beyond the usual confines of NY studio apartments. His attention to detail is greater here than anywhere else, but the tone is hampered by a strict adherence to DeLillo's original. Baumbach is at his best when his distinctive voice is heard, as in The Meyerowitz Stories or Marriage Story. Though he may have been one of the best choices for this film, he dilutes his style too much to allow DeLillo's to emerge.

The biggest problem is the multi-climaxes in the last act, which repeats the theme once too often, and once too literally. (I suggest not translating the German nun, so that we experience the situation closer to that of Babette and Jack.) It also has too many themes (consumerism, death, violence, ecological disaster, religion, academia), which a postmodern novel can handle better than a film. Nevertheless, it tackles these themes better than any other film with a $100 million budget and will be even more prophetic than it was in 1985 as the problems get worse.

White Noise is streaming on Netflix.

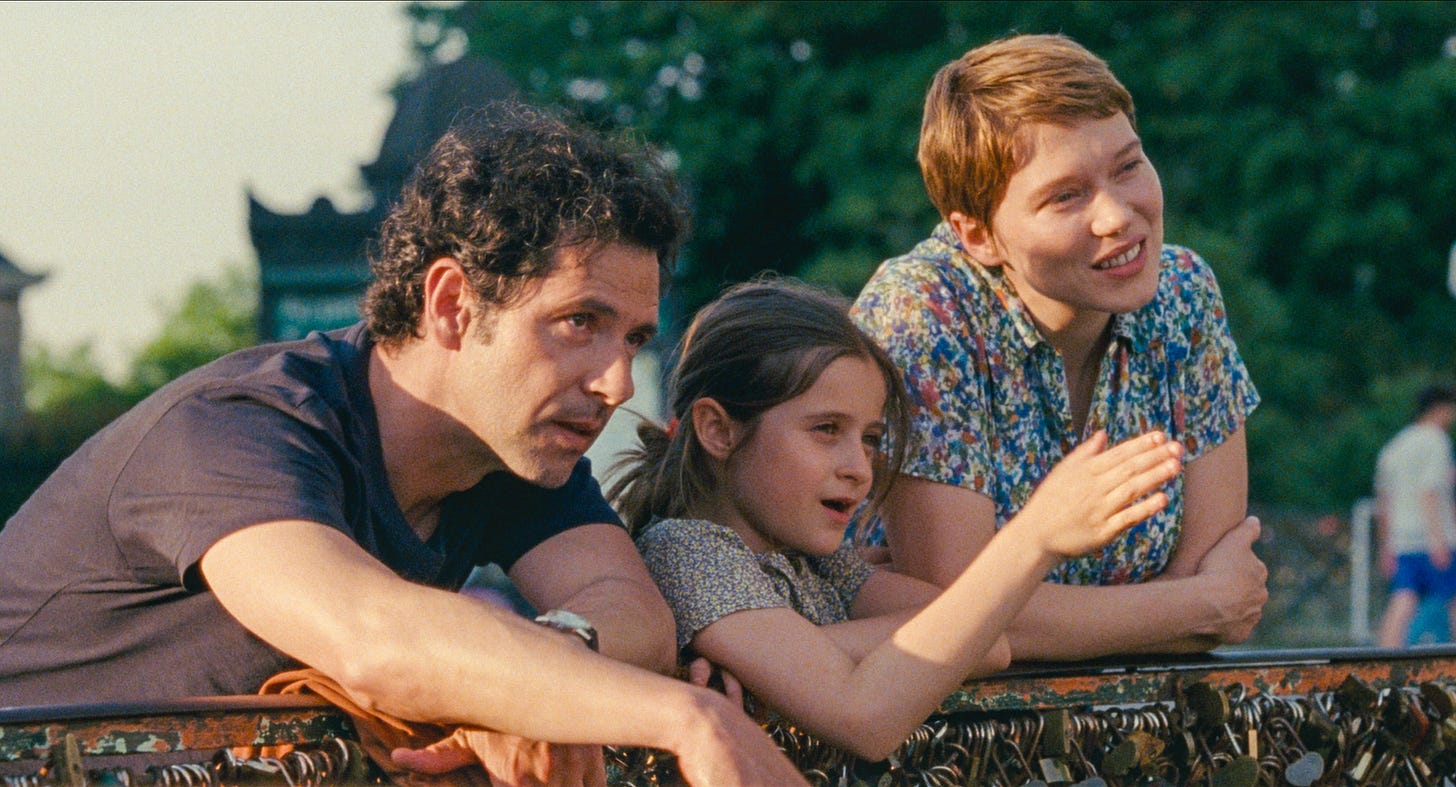

One Fine Morning (2022, Mia Hansen-Løve, France/Germany) is Hansen-Løve’s follow-up to my favorite film of 2021, Bergman Island. It stars a short-haired Léa Seydoux as Sandra, a single mother working as a freelance translator (German and English). Her father Georg (Rohmer regular Pascal Greggory), a famous academic, is deteriorating from a neurodegenerative disease and requires more assistance because of his impaired vision and rapid memory loss. Sandra’s daily malaise advances as steadily as her father’s disease until an infatuation with Clément (Melvil Poupaud), a married man in a stalled marriage, begins.

These two threads continue to converge until the third act, where we get the thesis of what “one fine morning,” translated into French from German (an einem schönen Morgen), which forms the original title, Un beau matin, is. Georg’s regimented and highly mental-dependent life failed to operate as it once did, leaving him in a state of constant confusion and panic attacks. Sandra’s similarly postponed romantic life has been inactive for five years and would’ve continued indefinitely. Instead of being the problem of a single mother in Paris, we’re all stuck in a loop of daily tasks that builds into weeks, months, and years. The promise of a beautiful morning is a living daydream people can use to escape from the black hole of passing time. One Fine Morning suggests this comes almost entirely to chance, whether by old-age disease or crossing paths with old friends. But they happen inversely: Georg’s life of order turns to chaos when it's impeded while Sandra’s life of order is prevented from turning into chaos through an impediment. On one fine morning is where they intersect.

In typical French film fashion, the affair is nonjudgmental and going in the direction of morally correct. Seydoux does an excellent job not reducing the role into a melodramatic mess and Greggory can make any hardened edge quiver with sympathy. Although the plot drags on in the second act and moments feel repetitive, it continues to enchant through the slow burn. The drama is felt through mundane drudgery that is rarely lifted, but when it does, we get a show-stopping Christmas scene.

One Fine Morning is playing in a couple Laemmle theaters in Los Angeles. Otherwise, you’ll have to put this on your watchlist and wait.

Broker (2022, Hirokazu Kore-eda, South Korea) is a Korean film written and directed by Japanese director, Hirokazu Kore-eda, who won the Palme d’Or in 2018 for Shoplifters. Kore-eda chose to do the story in South Korea because of his interest in working with three Korean actors: Bae Doona, Gang Dong-won, and Song Kang-ho (Bong Joon-ho’s number one guy). It also plays well as a Korean film because of the baby box plot, which is an anonymous place where babies can be given up akin to the American firehouse drop-off. Lee Ji-eun, a famous Korean singer-songwriter, plays a young woman who drops off her baby at one of these baby boxes. Although located at a church, two men (Gang and Song), proprietors of a struggling laundromat and occasional orphan brokers (the latter being highly illegal and I’m sure they’re cutting corners at the laundromat), retrieve the baby to sell off for a profit. The young mother regrets her abandonment and comes back, but the brokers already have clients lined up. She decides to follow the brokers on various road trips to potential buyers while a female detective pair (Bae and Lee Joo-young) is following them.

The plot requires sometimes large suspensions of disbelief for the familial conceit to work. Why don’t they just give the young woman her baby back? Why is the mother willingly going along? Answer: the journey is more important than the destination. Especially since one can see the ending around every beat. The viewer knows they will come together as a make-shift family, but how? This is where Kore-eda’s cinema excels. The pain of loss and coming together is felt through the relative loneliness of each character. They’re the scraps at the end of a meal that form a delicious coda, no matter their incongruity. The film is beautiful in winning over the judgment easily associated with one side or the other. The mess of underground adoption and parents outside the normal boundaries of nuclear life is messy for the opposite reasons. The fact of their existence, and the measures they take, show a broken social contract self-adjusting, which Kore-eda explores in his previous films as well.

Broker is playing in theaters with a limited release.

Pass

Nothing this week.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t already done so.