2022 Films: Curtis, Spielberg, Guadagnino, and Schrader, Weekly Reel #42

The first Weekly Reel to cover recent (English-language) releases, from TraumaZone to The Fabelmans, and from Bones and All to She Said.

News of the Week: I will be taking off two or three weeks in December, through New Year’s Day, to recharge my batteries. In that time, I’ll have standalone posts edited and ready to go early next year.

Watch Now

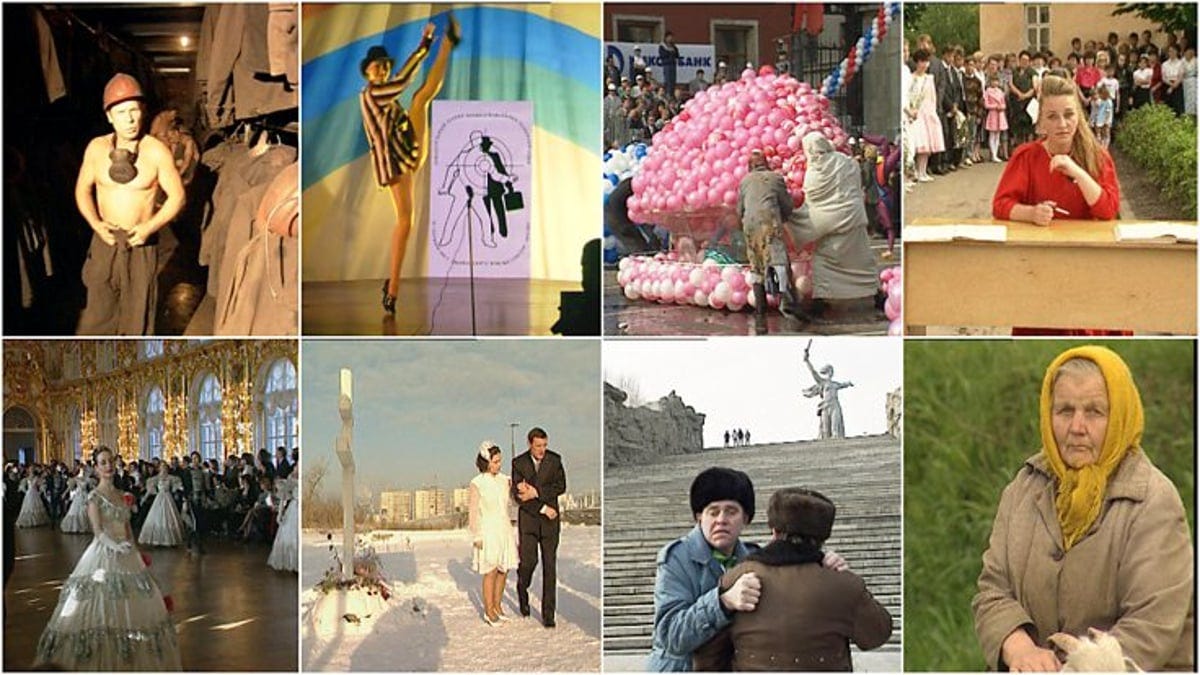

Russia 1985–1999: TraumaZone (2022, Adam Curtis, UK) is the newest Adam Curtis doc, this time digging into the fall of the Soviet Union and rise of authoritarian/nationalist Russia. He uses thousands of hours of BBC footage from the era to document the transitional collapse from the ground up. We watch a charismatic seven year old begging in long lines of traffic; a Togliatti car plant falling prey to gangsters after Soviet price controls were lifted via perestroika; a female juvenile detention center in Moscow; street vendors selling their household items to make up for the loss in financial value; an oil pipeline that exploded in Siberia; villagers all over frozen landscapes wondering how they’ll make money; and hundreds of other videos from the streets in Moscow to the small villages to the miners of Ukraine and military conflicts in the steppes. They provide a montage of despair, a pastiche of pain and empathy that makes one feel the Russian people haven’t had their voices heard in a very long time.

The biggest difference with other Curtis docs is his suppression of voiceover and non-diegetic music, which were his strengths. His reason being that “the material was so strong that I didn’t want to intrude pointlessly, but rather let viewers simply experience what was happening, because it is was out of this – the anger, violence, desperation and overwhelming corruption – that Vladimir Putin emerged.” (Curtis wrote this short companion piece for the Guardian that acts as a decent TL;DR for this seven hour doc.) The images reveal the faces of those living through the times, which often shows them grimaced, empty, and/or anxious. These are set in high contrast to the images at the Kremlin and other elite institutions hoarding the money. We watch a lavish ball in a pre-Soviet Russian Empire restored villa as well as the new oligarchs gaming the system and bending communist officials, and “capitalist” ones, to their financial will. And while I miss the Curtis voiceover and electronic/industrial soundtracks, the images and words speak for themselves.

After watching the seven hours of footage with text on screen explaining where they are and what’s happening, one feels deflated. It’s obvious the Russians and Ukrainians and others had no chance at determining their own destinies. That was made up by those who exploited the collapsing Soviet system for financial and political gain (as well as the American economists backed publicly by Bush 1 and Clinton who gave the oligarchs a blueprint), which made a bad situation worse. When Putin finally showed up in the last few minutes of the final episode, his anonymous rise appeared inevitable because of the previous fifteen-year downward trajectory.

If you live in the UK or have a VPN, you can stream the doc on the BBC iPlayer. Or you can watch the episodes on YouTube, in shittier quality, along with all of Curtis’s docs.

Save for Later

The Fabelmans (2022, Steven Spielberg, USA) is the long-awaited Spielberg flick that everybody and nobody wanted. In the film, he retreats into the unexplored frontier of life writing, the cinematic genre currently in vogue, to commercialize his life of figuring out how to make commercial films. In the film, there are many references to other films (The Greatest Show on Earth, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Blow-Up, and even a nod towards The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station). Starting in 1952, his childhood fascination with film began and gripped him for seventy years. He grows up in a Jewish household with a scientist father (Paul Dano) and musician mother (Michelle Williams), the latter encouraging Sam (Mateo Zoryon Francis-DeFord) to pursue his interest. In a spoon-fed dialogue to stick the point further into your mushy brain, which Spielberg thinks is off for most of the audience, Sam’s uncle (Judd Hirsch) tells him that he’ll have to pick between filmmaking and his family: “Family, art. It will tear you in two.”

Spielberg hasn’t had much difficulty mining his parent’s divorce for resonant source material to make his millions. The story is framed between his artistic mother and rational father, implying that he chose the former for his career. Not so fast. In an elliptical take on one’s upbringing, Spielberg reveals more in what he omits (massive amounts of time watching fifties and sixties television, which provided his commercial understanding of video) than reveals (how clever and natural his early mind was in the method of filmmaking). But if anything, the story he tells, and what bears out in his career, shows that he followed his father’s path rather than his mother’s. Spielberg’s history in Hollywood is one of financial successes married to ingenious filmmaking techniques, much like his father’s success as a creative computer engineer. In both, resourcefulness in the science of their apparatus led to financial gain. Can anyone say, with a straight face, that Spielberg has made anything more artistic than commercial?

The final scene with David Lynch, the most well-known American artistic filmmaker, is a kind of self-deprecating joke, which is rare for SS. I’m ultimately not sure what this film is about—his parent’s divorce, high school melodrama, making films, celebrating films—other than being the final statement in a career built on fictionalizing suburban families and parental disputes. And the more obvious references to his own work—E.T. and Catch Me If You Can are the most notable of many—turn out to be lesser versions of their fictionalized re-enactments in The Fabelmans, which can always fall back on being a “fictional portrayal.” Is this film better for those familiar with film history and Spielberg’s filmography than those who aren’t? I’m not sure and don’t really care.

It's playing in a theater near you.

Bones and All (2022, Luca Guadagnino, USA/UK/Italy) is the delicious midnight Aglio e Olio to Guadagnino’s last film with Timothée Chalamet and Michael Stuhlbarg. It stars Taylor Russell as Maren Yearly, a teen-ager who has the uncontrollable urge to eat human flesh, which forces her and her single father (André Holland) to constantly move. When Maren turns eighteen, her father leaves her with some cash, a tape recording of his experiences with her cannibal past, and her birth certificate. On the record, it shows the town where her mother was born, so she ventures there to find out more about herself, her past, and her mother—who we’re guessing is also a cannibal.

At one of the Greyhound bus stops, Mark Rylance, as final boss cannibal drifter, sniffs out Maren from half a mile and invites her to “his” place. She finds out that he’s squatting at a dying woman’s home, which he had found through his heightened ability for smells. After feasting together on the woman when she finally dies, Maren leaves without saying goodbye after he teaches her the fundamentals of cannibalism sniffs. On another stop in Indiana, she meets Lee (Chalamet), who’s also an eater, but a cute one. Lee takes his eating to another level by killing someone who was drinking a beer and making a nuisance at a grocery store. Maren is still full from the fat old lady, but she decides to ride with him to find out more about who she is (while also getting a ride to her mother’s town). Through the trials of their growth together, including a great cameo by Michael Stuhlbarg in his best The Texas Chainsaw Massacre outfit, Maren and Lee learn how to live together as eaters even though their outsider status (and flesh eating hunger) prevents a full union.

The tone of the film switches, dramatically, between romance (Call Me by Your Name) and body horror (Suspiria). But like in Cronenberg’s recent Crimes of the Future, the violence of pierced flesh is treated like a quotidian activity. It’s something they all do, naturally, but are discouraged by our era of cannibalism no-no. At first the Big Metaphor appears to be sexuality. There’s even a homosexual scene to further that theory. But that mostly falls apart with its emphasis on the generational trauma inflicted on both Maren and Lee. It’s more of a post-vampiric (post-industrial) rust-belt story about two lonely hearts hunting together. Nature triumphs over nurture and they’re trying to correct that wrong.

Bones and All will be playing in theaters for a little while longer.

She Said (2022, Maria Schrader, USA) is another tepid journalism procedural that shows that as we get further away from All the President’s Men, these types of films are less effective. I’m guessing this is because the job itself has been reset to its rightful place as a less prestigious career path rather than a maverick profession for the moral guardians of the USA, exposers of all the ills and injustices behind the scenes. Woodward and Bernstein, along with Pakula’s film, changed the image of American journalism into a lofty elitism that’s had its paint chipping off ever since. After the repeal of the fairness doctrine and rise in television news, the American psyche never had a chance.

But that isn’t to say all journalism is corrupt or biased. In She Said, we follow the story of two NYT journalists covering the Weinstein abuses, trying to rush it out before Farrow’s New Yorker piece on the same topic. (Both Farrow’s Catch and Kill and Kantor and Twohey’s She Said are excellent books detailing how difficult it was publishing the Weinstein stories, but I think Farrow’s would’ve been the better cinematic adaptation. Also, a couple of the victims said that they trusted Farrow more because the NYT previously suppressed a story on Weinstein’s sexual assault.) She Said revolves around Kantor and Twohey’s attempts at getting Weinstein’s victims, some under NDAs, to go on the record so that the story could have the legitimacy of journalist ethics. But that’s as far as the tension goes. The New Yorker review of the film likened the two journalist to therapists compared to the spycraft of Deep Throat. We know the outcome and there are relatively few hiccups (especially compared to Farrow’s journey).

The weight of the story and its implications in beginning the #metoo era is impossible to understate, but that still isn’t enough to push this film into something great. I would recommend reading the two books and then waiting for this film’s release on a streaming service.

Pass

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t already done so.