Aftersun, the Best Film of the Year, Weekly Reel #40

International cinema strikes again with Aftersun by Charlotte Wells, Armageddon Time by James Gray is good but not great, and, of course, a French film from the sixties

News of the Week: with Netflix launching their ad-tier last week, Disney next month, and Apple TV+ next year, advertisers are accomplishing the hostile takeover they’ve been dreaming of since cord-cutting entered the lexicon. And with these tiers, regular no-ad tiers are going up in price for the sake of “inflation.” This won’t augur well…

Watch Now

Aftersun (2022, Charlotte Wells, UK/USA) is the brilliant debut feature of Charlotte Wells, a young Scotswoman etching her entry into the autobiographical filmmaking of Millennials. It takes place in the late-nineties on the Turkish coast where a thirty-two year old, Calum (The Lost Daughter’s Paul Mescal), is staying at a British-themed resort with his eleven year old daughter, Sophie (Frankie Corio). It begins with MiniDV footage of the trip, where we learn their birthdays are a couple of days apart, which is the reason for the trip. The confused distance between nineties’ tape quality and the box television reflection creates a mood that sustains the theme of the film. Before entering their vacation, we watch strobe-light rave footage with Calum dancing. At the resort, the pair swim, apply sunblock on one another, and get confused for brother-sister. We quickly perceive that this is one of the only times they get alone, and that Calum is using his Tai Chi to work through issues while keeping a straight face in front of his daughter. The POV is clearly Sophie’s, who’s trying to decipher her father while observing the PDA of other vacationers using her pre-teen faculties.

Although distant from one another on a deeper emotional level, the two get along good enough to have a pleasant time. There’s a time later in the film where their tensions reach a breaking point, which reveals the extent to which his personal problems (I’m guessing a history of depression and/or substance abuse) and her introduction to intimacy have been present under the surface, thinly, the entire trip. But this all works as a reverie. Then comes the hammer to the gut in the final moments, which—I’ll only spoil a tiny bit—features the amazing vocals-isolated track of “Under Pressure.” If that doesn’t move you, then you’re denser than a black hole. (That’s about two quadrillion grams per cubic cm; and for you lazy Americans, that’s about 72,254,335,000,000 pounds per cubic inch.)

Charlotte Wells, in her first feature outing, already mastered the trite “show don’t tell” rule of respectable filmmaking. It’s something few directors and writers perform with ease, preferring to spoon-feed exposition for fear of losing the audience. When a filmmaker can show all the relevant details, like Wells does with Calum’s problems and Sophie’s expressive POV, it shows a director authoring a work of art—or as close as possible to being a painter or author as the film medium distancing can allow. Wells took a couple of years of sitting on the script to find the core of the film, that of Wells projecting an understanding of herself (as Sophie) onto her father (as Calum). Through the memories of the trip, aided by old tapes, Sophie, in present-day feeling a melancholy reminiscent of how she saw her father’s, reaches an empathy difficult to depict on screen. And by showing all without telling us what’s going on internally, Wells magnificently portrays how memories are hazy images projected from the standard-definition tapes onto a giant high-definition flatscreen.

The best part is that Wells makes a distinct period piece that doesn’t go too far into nineties nostalgia. The nineties-kids will still get their KiX, the tucked-shirts and og-unironic “Macarena,” but Wells leaves behind the aesthetic artifacts of that age in return for its memories and the media used for its recollected storage. The film is distributed by A24 in the USA (Mubi worldwide), which also distributed Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight in 2016. Similar in ways that one’s history reflects through projections from the past without reverting to nostalgia, Moonlight and Aftersun also share a producer, Adele Romanski, who was the motivating factor for both Jenkins and Wells to film their stories. (Jenkins had co-written Moonlight’s script with a childhood friend whom he saw as a reflection of himself.)

You can catch Aftersun in theaters for a limited time. Its American distribution isn’t guaranteed a soon streaming release, but A24’s close relations with Apple TV+ may come into play. But why waste the chance of crying in public at a movie theater?

Save for Later

Armageddon Time (2022, James Gray, USA) is another life writing story. This story was inspired by James Gray’s upbringing in an eighties NY, Jewish-Ukrainian household. Like Gray’s eleven year old stand-in Paul Graff (Banks Repeta), the family name was shortened to fit into American society. Paul lives with his parents (Anne Hathaway and Jeremy Strong), but his closest friend is his grandfather (Anthony Hopkins), who provides Paul with lessons in ethics and integrity. In public school, Paul befriends Johnny (Jaylin Webb), another classroom disruptor from day one who was (most likely) held back a grade because he is black. The pair grows their friendship through detention together and being, as many kids are, outcasts.

If it weren’t for their family backgrounds, the two would proceed down their life-routes in an ideal forward line. Paul wants to be an artist; Johnny wants to be an astronaut. But Paul lives in a middle-class house surrounded by family while Johnny lives in another borough with his invalid grandmother. One day, Johnny brings a small joint and the two smoke it in a bathroom stall while they were supposed to be cleaning the class paint brushes. Their teacher catches them, and they receive punishments entirely discriminatory based on their privilege levels. Paul changes to a private school that his older brother is attending—one where Fred Trump and his daughter Maryanne (DJ’s brother, played by Jessica Chastain) provide library funding and give the occasional talk—and Johnny drops out of school. Child Services is looking for Johnny because his grandmother can’t support him, so he hides out in Paul’s backyard wood hut. Although Jewish and not far removed from ancestral immigration, Paul’s upward punishment relative to Johnny shows the groups benefiting most from (white) societal integration. And it gets worse from there.

Whereas Aftersun is intensely personal, fragmented, and surrealistic, Armageddon Time is social realism. It sketches a sociological question: what happens to two kids of divergent backgrounds in the same trouble? The results are unfortunately standard and predictable. And that’s what holds Gray back from crafting something revelatory and cinematic. The story is held together by the performances, especially from Hopkins and Webb, who are sixty-eight years apart in age. Nonetheless, the film is extremely solid and is still in theaters.

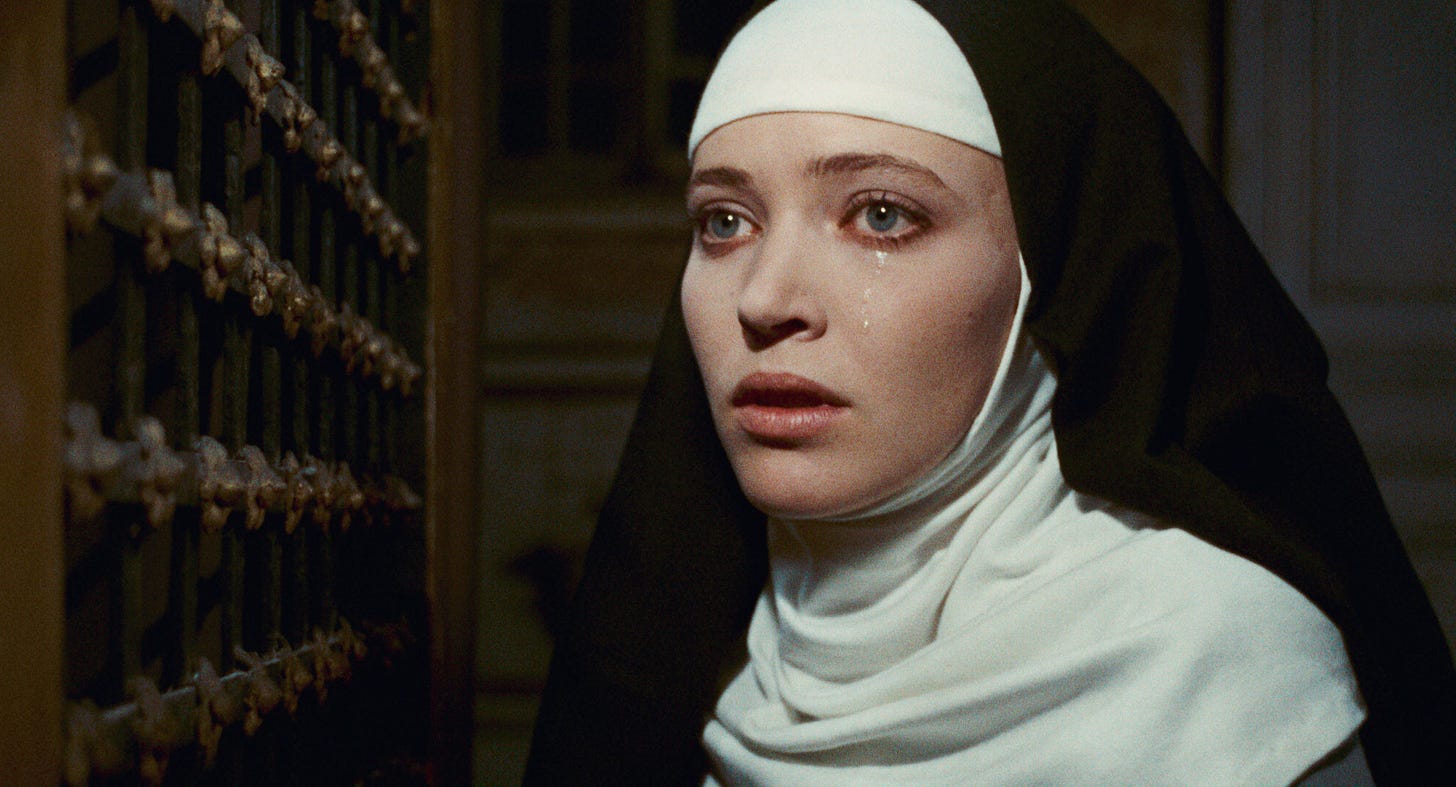

La Religieuse (eng. The Nun, 1966, Jacques Rivette, France) is a New Wave film based on the book of the same title by Denis Diderot. It’s about a nun, Suzanne Simonin (Anna Karina), who is forced against her will to pledge herself to God and the nunnery. She’s open about her hostility being there, which Mother Superior tries to quell through long conversations and motherly surrogation. But then that MS dies, along with Suzanne’s actual mother, and the new MS isn’t sympathetic with Suzanne’s frustrations. She sees her as transgressing against God and their convent in a satany manner. Suzanne begins litigation against her conditions, which leads to MS taking away her linens and other little freedoms. The nuns suspect the Devil is at play the closer the lawsuit gets to trial, which forces MS and Suzanne in front of another Man of God for questioning.

At this point, Suzanne is in full rebellion rags while the nuns are planning a dank exorcism. Then like an angel, someone supports her dowery to move into another convent. Suzanne is excited, but the new convent is an extremely liberal version—they take off their wimples in public! The MS there takes Suzanne closer than just under her wings, which repels Suzanne. She escapes with the help of a lusty monk, whom she also escapes from. She does odd jobs and begs until a women allows her to work a chic brothel. When Suzanne realizes what’s going on, she throws herself out the window after asking for God’s forgiveness. (I don’t normally spoil an entire film’s plot, but I know none of you are going to watch a 135-minute, sixties French movie about nuns lol.)

Anna Karina, my favorite French—and top three regardless of nationality—actor is perfect for the role of a nun with her massive eyes and mouth being able to express better through that headwrap than anyone else. I’m still in mourning over her Dec. 2019 death as well as the fresher expiration of her first husband, JLG, in Sep. 2022. The story of Diderot’s writing of the novel in the 1770’s is fun: he began writing correspondence to a friend, Marquis de Croismare, posing as a young nun sent to a convent against her will. The Marquis, a decade before, participated in a similar case with a young nun wanting to live a free life. (She was confined her entire life.) Although Diderot was writing the letters as a joke against his companion, he became passionate about crafting the story into a novel about the corruption of the Catholic Church and nunnery hierarchy. Diderot had to take a break from being the co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the original Encyclopédie. The novel wouldn’t reach publication until 1792 along with the establishment of the anti-clerical First French Republic and Culte de la Raison.

Anyway, if any of that appeals to you, then you can find La Religieuse streaming on Kanopy.

Pass

Sisters (1972, Brian De Palma, USA) was De Palma’s first horror/thriller in a long line of classics that would make his name synonymous with neo-Hitchcock and solidify his place in New Hollywood. Sisters, which Tarantino’s devotes an entire chapter to in his new book, is about a woman experiencing psychological problems from having been separated from her Siamese twin. The split screens and tracking shots show De Palma’s mastery of cinematic art, which would make his seventies and eighties films classics, but for this film feels like an exercise devoid of an appealing story. I’m not a fan of horror, so that certainly colors my view of the film. Maybe Tarantino can prove me wrong…

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t already done so.