Bill Burr & Comedic License

What role do stand-up comics play in contemporary society?

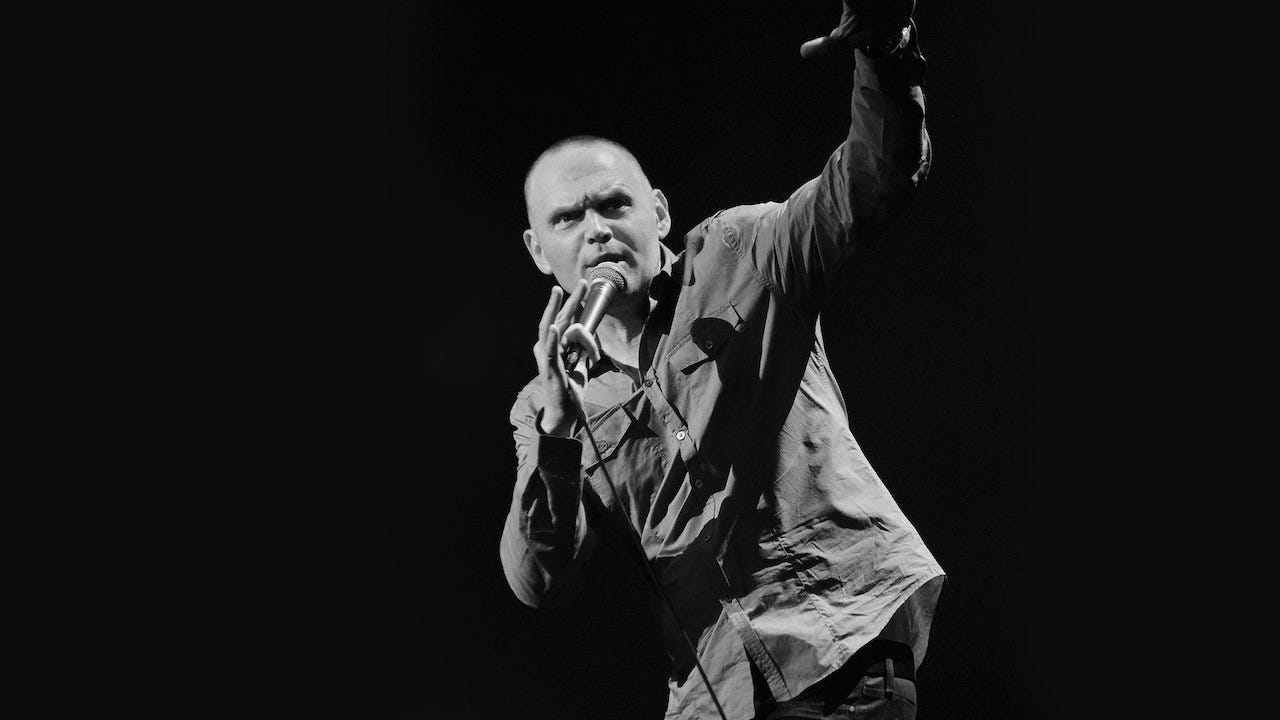

Unlike artistic license and its popular sub-categories, poetic and dramatic license, comedic license remains little explored in academic texts, online articles, or reference books, and only discussed implicity among stand-up fans. Therefore, I wish to explore the function of comedic license and apply it to stand-up comedy. To use a specific example, I examine Bill Burr’s bits from three of his stand-up specials.

The Fool’s Comedic License

Artistic license is defined as the freedom to act and specifically the act of “breaking rules or principles” for the creation of art. Whether its poets writing poetry, filmmakers shooting films, or comedians performing jokes, this loosely defined license is the figurative guarantor of the former achieving the latter. Poetic license is further defined as the right given to poets to go beyond standard conventions for their writing. Comedic license is also a right, not a privilege, meaning the freedom afforded to the stand-up comedian is inherent rather than conditionally granted, or privileged, by the State or culture in general.

To reach a fuller definition of comedic license, a short history of the fool is needed to find where that license first proliferated in any Anglophone medium.

The medieval court jester, or fool, was popularized in Shakespeare’s plays: for example, Touchstone in As You Like It and Feste in Twelfth Night. Feste, Olivia’s fool or ‘clown’ as named in the text is perhaps the most intelligent character in the play; he keeps his distance from the diegetic action because of his unique social position, thus enabling him to create a dialogue with the reader by providing witticisms about the play’s actions and characters as a fellow detached observer. Feste walks in and out of conversations with relative immunity regarding social customs while being paid to perform songs and provide wit on command. The license afforded to the fool gives them a unique position outside the socio-cultural norms to comment upon them but close enough to still be included.

In the 1962 study, Heroes, Villains, and Fools, Orrin E. Klapp begins his chapter on fools by stating that the “ridicule and wit make plain to us the folly, humbug, and incompetence of the social structure. For this kind of truth (consensus) the fool is institutionalized” across most cultures. This universal need for the fool’s ability is predicated upon the “sublimation of aggression, relief from routine and discipline, control by ridicule (less severe and disruptive than vilification), affirming standards of propriety (paradoxically by flouting followed by comic punishment),and unification through…the communion of laughter.” Klapp goes on to characterize fool types, the jester being the closest to what Feste and stand-up comedians embody: fool-makers whose duty is to make fun of others via social critique. To do so the fool “may assume a pose of rusticity or ignorance.” This is why Malvolio tells Feste, “infirmity, that decays the wise, doth ever make the better fool.”

There are numerous paradoxes as to what comedic license permits the fool figure as opposed to other members of society: societal inclusion with an outsider status, ridicule of self and others, intelligence and foolishness, freedom and property of the court, and finally, deviant and ceremonial priest. These binaries are sealed by the license, one reverberating off the other in harmonious unison. How can these paradoxes then be applied to stand-up comics?

Lawrence E. Mintz, in his socio-cultural analysis of stand-up comedy, finds “the key to understanding the role of standup comedy in the…recognition of the comedian’s traditional license for deviate behavior and expression.” The stand-up comedian as marginal or defective is granted permission to travel beyond social conventions, that the audience laughs at the comic because of their, the audiences, superiority in not sharing the same weaknesses as the comic, using laughter as a “mild punishment.” And though the audience may laugh at the comic, the audience also identifies with the deviant behavior and “[recognizes] it as reflecting natural tendencies in human activity” whereby the comedian then becomes “comic spokesperson.” The connection between the fool, or stand-up comedian, and the audience therefore takes in a further paradoxical binary of audiences laughing at and with stand-up comedians.

Bill Burr is known for his particular type of rage-humor, which is characterized by frequent shouting and perceived anger at the material he is delivering, perhaps because of a bad temper. He addresses this in Let It Go when he jokingly dismisses these outbursts as him being “passionate.” In his following special, You People Are All the Same, he has a bit, a short joke or anecdote, about his temper in the context of fixing objects around the house (all transcriptions done myself):

So I'm learning how to fix shit, right? My girlfriend doesn't like it 'cause she says I have a temper, you know? She's like, “you know, it’s just not that you're trying to fix things, it’s that you get frustrated, you punch the wall, the dog starts shaking. I just don't think it’s a good idea…you know, you're a comedian, you should tell jokes, he's a plumber, he should plumb, right?”...I'm trying to explain to her that losing your shit is part of the process of fixing something. Right? Everybody does that. You buy, right? Yeah…you buy something at Ikea, you get halfway through putting it together, your like, dude, where the fuck is the fucking!—, oh, there it is, there it is, there it is.

This bit not only shows Burr’s willingness to use his temper as a device for self-reflective humor, but also to show what Burr’s deviate and marginal characteristic is: a bad temper that leads to shouting that upsets his significant other and peevish dog. He’s given the ability to perform this bit and have it succeed, as Mintz might argue, because the audience either enjoys feeling superior by not having a temper, laughing at him, or recognizes in Burr something within them that they are not permitted to expose themselves, laughing with him. Burr is therefore granted the comedic license, rooted in the fools and clowns of the past, precisely because he performs a public action for the audience, which is the taking out of anger through yelling and swearing for those who are seeking out relief from societal pressures. Unconscious or not, Burr located a hidden impulse common enough in societal excess that it needed a fool figure to articulate it in a comedic, relieving method.

To conclude the section, Shakespeare via Olivia regarding the fool, Feste, said:

This fellow is wise enough to play the fool;

And to do that well craves a kind of wit:

He must observe their mood on whom he jests,

The quality of persons, and the time,

And, like the haggard, cheque at every feather

That comes before his eye. This is a practise

As full of labour as a wise man's art

For folly that he wisely shows is fit;

But wise men, folly-fall'n, quite taint their wit.

Audience-Comic Intimacy

The audience, besides the physical stage and microphone, is the most important physical tool used by the comic to achieve their goal of laughter. Although comedic license grants a comic the ability to transcend the embarrassment and ridicule of exposure, it doesn’t guarantee it. Another paradox of the license then emerges, which is that during a stand-up performance, there is a negotiation happening between controlling the audience and being controlled by the audience, where the comedian must be able to constitute a solid identity and identification with the audience concurrently.

Hecklers play an important function that gauge the audience’s position vis-à-vis the stand-up comic by shouting out during the performance if they feel offended, don’t like the jokes, or are too drunk. If the comedian responds, they usually verbally ridicule the heckler to varying degrees of severity. In Burr’s You People Are All the Same, an unknown female shouted out during an offensive bit about women and Burr dismissed the heckler with mild verbal scorn while getting a positive response from the audience. While that lone heckler was certainly in the minority, the audience at large displayed an antagonism towards the heckler rather than the comic, as can be witnessed by the laughter and clapping after Burr’s scorn, which further built the audience-comic relationship.

Laughter as a prescription for social corrective was popularized by the oft-cited Henri Bergson essay “Laughter,” in which he argues that “in laughter we always find an unavowed intention to humiliate, and consequently to correct our neighbour, if not in his will, at least in his deed." Thus, the stand-up comedian is having a dialogue with the audience in a privileged position, where that privilege is granted by their ability to commit to an exchange of ideas that deliberately provokes the re-affirmation or subversion of status quo beliefs held by the recipient. That privilege turns into a right when that provocation leads to necessary social correction.

To recall a bit that is socially subversive and improves the intimacy of the audience-comic relationship from Bill Burr’s 2014, I’m Sorry You Feel That Way, it centers on the growing cultural phenomenon of transgenderism, a relatively new and taboo topic of discussion. Burr specifically focuses on sports:

I'll get in trouble later on in my life, transgender athletes? I don't fucking understand that, you know? I understand it, if, you know, you want to switch around I don't give a shit, but I'm a sports fan…that's a really new concept to me, that you could be a dude, right? Ranked 80th in the fucking world, then you have your dick cut off, you put on a sports bra, and now you're the number one tennis player in the world just coming out there with your man shoulders. [Performs tennis movements with manly groans.] That doesn't seem fair, I might be wrong. I might just be an old guy, I have no idea. But I'm hearing rumors like some of them are getting into that MMA. You can't have that shit. Am I nuts? That is a dickless dude beating the shit out of a woman…Jesus Christ, he might as well hit her with his discarded dick like a flashlight. [Performs hitting motions with the imaginary object.] “Hold still. Her ground and pound is incredible”…yeah. I'm not saying these people are right, and I'm not saying that I'm right. I know I'm a fucking moron, ya know…

This bit has multiple interesting elements. First is the appeal to ignorance, as marginalization, in the final line that disarms his critical statement as the ramblings of a curmudgeon not to be taken seriously. Next is his reflexive and (probably) unconscious use of ‘ya know?’ and its variants, which, along with direct eye-contact, continually re-establishes and confirms the intimacy between Burr and his audience. It acts like a metaphorical pulse-check on the audience to make sure they’re following the line of thought, which could be wildly misconstrued.

Lastly, there’s the destabilizing pronouncement of questioning a socially taboo subject matter. Although offensive humor is covered in the following section, Brodie’s small-talk framework is appropriate in analyzing the situation; Burr produces an ambiguity in his speech on the role of transgender people in sports by stating, “I might be wrong” and “I have no idea,” which confuses the joke narrative from the belief statement, what he essentially thinks to be true. Comedic license permits him this kind of tightrope walk, with harmful consequences if the paradoxes aren’t balanced correctly.

The three methods of ignorance, intimacy, and ambiguity combine in order to form the basis of Burr’s joke, which is then legitimized through the audience’s laughter and participation.

The License to Offend?

Freud divides innocent jokes from tendentious jokes, the latter having an aggressive or exposing purpose that makes it offensive and directed at someone not present. The court fool can perform their caricatures and satires of authority, according to tendentious theory, because these kinds of hostile jokes represent a rebellion against authority and a “liberation from its pressure.” Freud argues that civilization represses pleasure and censors enjoyment; tendentious jokes provide a means of undoing that renunciation and retrieve what was repressed and censored, which effectively has no analogue in society and therefore makes it invaluable. This helps explain why fools and clowns are ubiquitous across cultures and time. While Freud looks at offensive jokes as a necessary steam valve to relieve pressure in a civilized society, Bergson claims that “by laughter, society avenges itself for the liberties taken with it.” Laughter as a social corrective is “intended to humiliate” the person it is directed against and “would fail in its object if it bore the stamp of sympathy or kindness." Generally, although not pleasurable for some, laughter and offensive jokes have an inherent privilege and uniqueness in society for the majority, which comics exploit through use of their license.

Bad taste is the basic criticism of offensive stand-up comedy today, mostly coming from the opinion pages of periodicals. Whether referred to as the politically correct or woke culture, the current zeitgeist of public American discourse is in flux, with many of the woke proponents reminding stand-up comics of their privilege and the consequences of making offensive jokes. Political correctness, though not new in American culture, is defined as the curbing of expressions and actions deemed offensive; woke or wokeness is generally defined as an awareness of socio-political issues. While the latter is modern slang for the former, both have to do with the perceived punching-down, tendentious jokes aimed at the less privileged in society, of stand-up comedians.

Writing in an opinion piece for the Sunday Times, Siphiwe Mpye claims that in the age of “patriarchy, racism, homophobia, misogyny, transphobia, [and] gender-based violence… reckless commentary, from columnists, artists and comedians cannot be allowed to thrive, no matter how ‘funny’ it is to those who are not the butt of the joke.” As defined by Freud and Bergson, effective jokes and laughter would have to be curbed since offense is built into their operational structure. Mpye says as much by concluding that the comic’s license to offend has been revoked. In a similar proponent’s opinion piece for The Guardian, Brian Logan evokes the same argument that jokes are frequently meant to offend and that reckless speech has its negative effects and harmful consequences in the real world. And like Mpye, Logan provides only vague references to what these harmful effects are, only that offensive jokes should not be tolerated.

Writing a month after Logan, also in The Guardian, Siyanda Mohutsiwa defines her own laughter at misogynist jokes as being silently complicit in the tragedies of life, making her feel like the tormentor and not the victim for a change and cites a Burr bit as an example. This controversial bit went as follows (for context, Burr is talking about getting into fights with his girlfriend when watching reality TV):

We have these huge battles. You know the maddest she ever got at me was? One time she was watching this show, it was like a poor excuse for The View and they start talking about domestic violence, you know, for like the nine-millionth time this year, their talking about domestic violence…..So at the end of the hour they come to logical conclusion, they're like, “there's no reason to hit a woman. There is no reason to hit a woman.” And I was just like, really?!, I could give you like 17 right off the top of my head…you could wake me from a drunken stupor, I could still give you like nine…dude, there's plenty of reasons to hit a woman, you just don't do it. But to sit there and suggest that there's no reason…dude, the level of ego behind that statement. What are you levitating above the rest of us? You're never annoying? Women, how many times have you thought about slapping your fucking guy in the head this week? [woman yelling from the audience: “everyday!”]…there you go, every day. You didn't do it, right? Oh dude, it drives me nuts, “there's no reason, there's no reason,” really? There's no reason? How ‘bout this, you marry a girl, you fall in love, you buy her a house, you go to work every day, paying off the house. You come home one day, she’s banging the next-door neighbor, hands you divorce papers, you gotta move out, sleep on a futon, and still pay for that house that she's gonna stay in. No reason?...I'm not saying you should do it, but there's plenty of fucking reasons in that arc of a story.

Burr continues the bit stressing that he isn’t condoning the physical abuse of women, only that the discussion of it shouldn’t be censored: "

I said you shouldn't hit a woman, I'm just saying, how come you can’t ask questions? You can only ask questions about what the guy did, you can never ask about the woman, why is that?

Writing for The New Yorker, Ian Crouch claims that social media is to blame for making audiences more sensitive and prone to feeling offended by stand-up comedians. Applying the small-talk intimacy theory, social media fails to simulate the original intimate performance vis-à-vis. Although commenting on an emotional subject, Burr’s speech grapples with the excesses of a societally taboo subject matter, and when the comedic license that normally grants an ambiguity between his jokes and declarative sentences is revoked, his small talk with the audience breaks down and leads to possible conflating and misapprehension.

So then what accounts for Mpye and Logan’s criticism? Are they merely making Freudian and Bergsonian arguments about jokes being offensive and humiliating, or trying to go further with declarations of censorship? The necessary question to then ask is who gets to determine what is offensive and what will be the consequences of offense? If it’s to eliminate all offensive jokes, then wouldn’t all jokes, according to Bergson, be eliminated?

What is killed by woke criticism is not the comedy, which will always survive because of its historico-cultural necessity, nor the inherent offensiveness of jokes, but the traditional comedic license. Criticism of jokes will be inevitable in perpetuum. The difference for contemporary audiences is the medium of consumption used to watch stand-up. With the proliferation of stand-up on YouTube and streaming services like HBO and Netflix, the new type of viewing pattern is distressing the form like it never experienced previously; more people are viewing specials, more social scrutiny is then placed on each joke, and because of social media, more people are taking jokes out of its original context and spread instantaneously. This then reduces the necessary comic-audience small-talk intimacy that makes subversion of social excesses a comic virtue.

Comedic license is a right, not a privilege, giving the stand-up comic the freedom to make jokes through public speech. That freedom comes with the license to offend through the necessary challenging of held assumptions, utilized by most societies through time to correct and be relieved of socio-cultural extremes. It allows for the ambiguity of control of relations to prevent any group from achieving full control of thought and expression. When one of those groups is granted power over the other, rights and freedoms will be leveraged against feelings, which will lead down the road of thought control. It is therefore our duty to protect those rights. As the liberal intellectual Noam Chomsky said, “If you believe in freedom of speech, you believe in freedom of speech for views you don’t like…If you’re in favor of freedom of speech, that means you’re in favor of freedom of speech precisely for views you despise. Otherwise you’re not in favor of freedom of speech.” Therefore it is our duty to protect comedic license.

All three Bill Burr stand-up specials can be found on Netflix.