Don’t Worry Darling, I’ve Got Other Viewing Recs, Weekly Reel #34

I go high on The Dirty Dozen, medium-high on Pearl, Beirut, and Moonage Daydream, and low-low on Don’t Worry Darling. Like Pugh, I wouldn’t want to promote the film either

News of the Week: My recently released article on Zora Neale Hurston won’t be for all of you, but maybe you know someone into literature or anthropology or American history, so please pass it on! Also, I’ll be posting another supplementary text this week on two recently released films that deserve more thoughts and words. Cheers. Thank you and I love you.

Watch Now

The Dirty Dozen (1967, Robert Aldrich, USA/UK) was a familiar first-watch for me because of my love of Inglourious Basterds. Tarantino stated that when he sat down to write the script, it was his Dirty Dozen. It’s the classic men-on-a-mission story, Tarantino replaced Lee Marvin with Brad Pitt and a dozen U.S. military convicts on death row or with twenty year sentences with a group of American Jews. Lee Marvin plays Major John Reisman, a rebellious officer given his final mission to redeem his standing. But the mission is suicidal at best. He’s given a dozen of the most mal-adjusted military men to train and drop behind enemy lines to raid a Nazi officer chateau ahead of D-Day—one must suspend their disbelief early in the film. The esprit de corps comes from the commitment and sincerity Reisman has with these men to get their sentences lifted. But that doesn’t not come with tough discipline and below-board methods of community building.

There are two scenes that Tarantino lifted. First is the lining up of the prisoners while Reisman gives them the introductory what-to-expect talk. Then, in the climax, with the burning of the Nazis and their collaborators in the chateau basement. The first instance is a spiritual lift while the second is a thesis on the power of film. It wasn’t lost on Tarantino that burning the Nazis in the basement—doors locked, gasoline poured in, and grenades launched—was an oven revanche. An Abrechnung der Konten. Tarantino took notes, traded out random Americans for Jewish Americans, and placed the Nazis in a cinema, the same tool they used en masse to mobilize a mass-genocide. Aldrich’s The Dirty Dozen revealed the power of cinema and then Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds unleashed the power of cinema.

The best parts of the film are in the long second act, which converts a group of misfits into combat-ready soldiers. There’s a gloom that surrounds the film, one being because most of these actors fought in the same war they were depicting—PTSD was at play with many of those veterans but seldom remarked upon—and the other because the film was released in 1967, the year Americans knew that Vietnam was a gross failure. Commanding officers, especially in the military, became suspects rather than liberators. And it’s that disrespect for authority that drives the group to embrace Reisman and do the mission together. The cast is stacked, but the best players are Lee Marvin, perennial film baddie turned leader of the rebels, and John Cassavetes, soon-to-be one of the most influential independent directors in U.S. film history, as the wildest bronco to tame.

In 1978, Italian director Enzo G. Castellari remade The Dirty Dozen and called it Quel maledetto treno blindato, literally “That damned armored train,” but was called “Inglorious Bastards” in the English-language market. Tarantino would later add “u” to the first word and change the second “a” for an “e” in the second. (On why he did that: “that’s just the way you say it.” Another reason is that Pitt’s character is illiterate, who engraves his rifle with the misspelling. Knowing Tarantino, there’s a chapter-long backstory to this we may never know.)

The Dirty Dozen is on Netflix, somehow, for now, so stream it there before they disappear it into un-licensed streaming territory.

Save for Later

Pearl (2022, Ti West, USA/Canada) is a prequel to Ti West’s X, which was released back in March. But you don’t need to have seen one for the other. While on production for X in location, West and Mia Goth, the main actor of both films, decided to start production on another story, about a young farm-girl who wants to become a movie star, immediately after wrapping on X. They re-worked the plot into an origin story of the main villain in X, who is an old lady on the farm that murders a low-budget porn crew shooting on the property. In Pearl, Goth plays Pearl, a young woman with a husband fighting in WW1 who is stuck on a farm taking care of her infirmed father and helping her German mother with household tasks. Pearl loves going into town to escape the farm for a couple of hours, but mostly because she gets to attend the theater. She dreams of becoming a major star one day, which comes along when her sister-in-law tells her about an audition. But since this is a horror film, it’s safe to say that she doesn’t nail the audition and become famous.

While X takes place in the nineteen-seventies and has a Texas Chainsaw, 16mm vibe, Pearl is brightly Technicolored in the nineteen-tens, looking strikingly like The Wizard of Oz. Mia Goth is our present Queen of Horror, who can play either subdued porn-star or electric farm-girl in the same year. And West has an endless supply of directorial vision that can call back the moods of different film eras better than anyone. When covid hit, West and his main creative friends were already quarantined on location, so they decided to just film another movie. The best part is that because they were in New Zealand, which was close to the production of Avatar: The Way of Water, West was able to use some of the already isolated crew members from Avatar to film Pearl.

This is horror month, and while I recommended Barbarian last week as the best possible choice for a theatrical fright, I think a double-feature of X and Pearl would be more net-enjoyable.

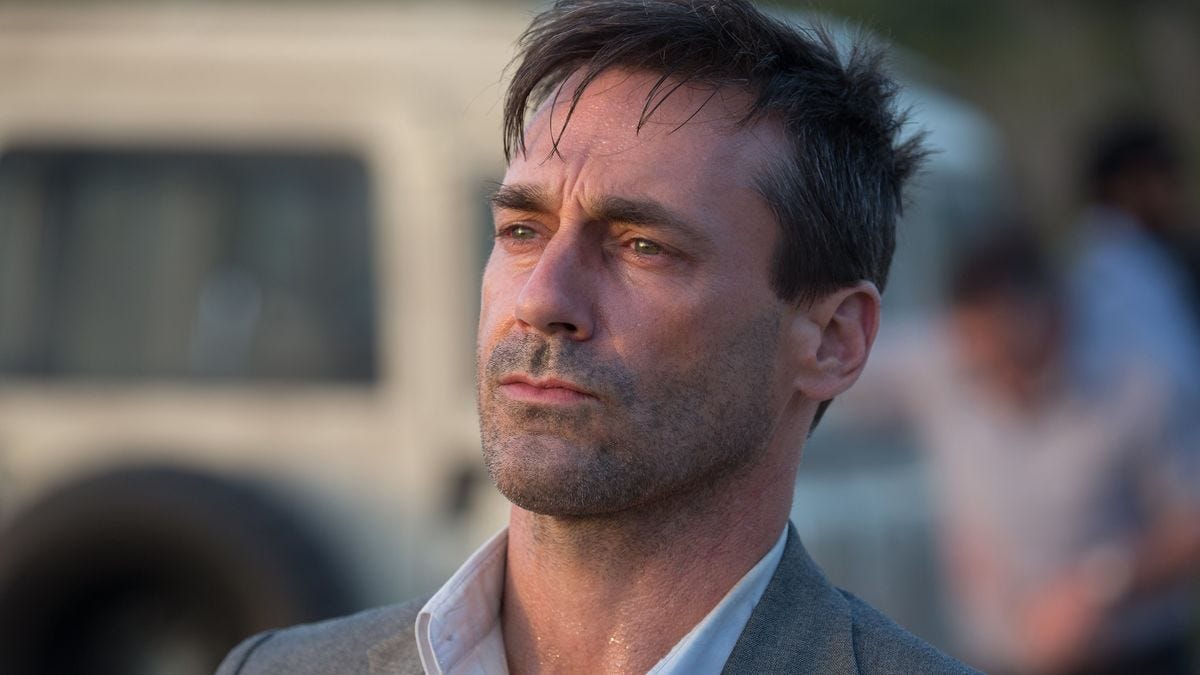

Beirut (2018, Brad Anderson, USA) is a political thriller starring Don Draper—who are we kidding, Jon Hamm doesn’t exist—who plays Mason Skiles, a gifted, multi-lingual, international relations negotiator. He’s living a happy life in Beirut with his wife and almost-adopted Palestinian butler-son working as a U.S. diplomat. It starts at a diplomatic party at his house; Skiles’ best friend, CIA agent Cal Riley (Mark Pellegrino), warns him that his Palestinian butler-son Karim (Yoav Sadian Rosenberg) has a terrorist brother who participated in the Munich hostage crisis, and that he’s wanted for questioning. Skiles refuses, knowing the thirteen-year-old to be a good kid, but then a small group of hooded dudes breaks in, extracts Karim, and kills Skiles’s wife in the crossfire. It’s revealed that Karim’s brother, Rafid, planned it. Skiles, now without son and wife, exits the diplomatic corps and works as a private entity negotiation settler.

But one day, a decade later, he’s brought back to Beirut, which had gone through a bloody civil war in that time, because a terrorist group took his friend Riley hostage, who has a wealth of diplomatic information that can’t spill, and the captivators ask for Skiles to negotiate with them for his release. Skiles is in the impossible position of helping his old bff in the city that took away everything from him. And of course, you can probably guess who chose Skiles, a washed up drunkard, to negotiate.

The film is a decently made middle-east political thriller that doesn’t delve too deep, wantoningly, into the politics until the end where it may have over-stepped the delicate balance it was holding. It’s no Munich in creating a sappy, accessible product for politics the filmmaker doesn’t care about but also doesn’t go into Zero Dark Thirty’s kill-‘em-all fuck politics. The film’s story tracts the psychology of Skiles and Karim, obviously the synecdoches of their nationalities, and doesn’t stray too far from that. Everyone is in a shitty situation. This is a scenario that the writer, Tony Gilroy (writer of the Bourne trilogy and writer/director of Michael Clayton), excels in: complicating traditional black-white characterizations. Mix that with a hidden conspiracy of people supposedly with your interests makes this film more enjoyable than the other political thrillers of goodies and baddies. If you feel so included, you can stream it on Netflix.

Moonage Daydream (2022, Brett Morgen, USA/Germany) is a kaleidoscopic, impressionistic documentary about the art and times of David Bowie. It starts and ends from his birth to death, but somehow told both out of order and chronologically. At one-hundred and forty minutes, it combines the officially sanctioned footage of Bowie’s life, from home reels/tapes/videos to interviews to experimental films to concert videos to behind the scenes featurettes to music videos to general archival pop-historical footage. Although this film won’t be for everyone, everyone was nonetheless affected by Bowie’s influence on pop-culture and can find something inside worth preserving. The film strikes the Bowie-as-persona bubble, but that isn’t new. His life was a wave of uncomfortable reckonings of who we are and what we’re doing here and how music is at its center. It’s hard to even write about a film so broad and focused, in but always out. The film is truly as close to a dream as one can imagine.

If you’re a Bowie fan, this film is a must-see as soon as possible. But for others, you can wait for its Spring 2023 release on HBO Max.

Pass

Don’t Worry Darling (2022, Olivia Wilde, USA) is a fitting example of a sophomore slump. Olivia Wilde’s first film Booksmart was smart, funny, and interesting but Don’t Worry Darling tries to be smart, is unfunny, and interesting for five minutes when one adds all the bits together. It stars a brilliant Florence Pugh married to Harry Styles, whose performance holds up like tower 7. Styles had several moments to flex—no doubt Shia LaBeouf would have been amazing—but ends up regressing to a lesser expressiveness than we saw in Dunkirk five years ago.

The script and direction is so repetitive and anticlimactic that Wilde tries to gaslight the audience into thinking her film about gaslighting is good. The slobbering reviews call this a smart, thinking-person flick; I’m sorry, are you high on glue? Intelligent scripts may have inspired it—Wilde gave the cast Inception and The Truman Show as homework—but don’t let it’s pristine nineteen-fifties (or is it the early sixties?) façade trick you into thinking you aren’t laying down in your shitty apartment hypnotizing yourself. I liked Nick Kroll’s performance.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t already done so.