Musical Bio-Pics, the Devils in Disguise and George Lazenby as Bond

Baz Luhrmann proves the musical bio-pic to be an empty exercise in flamboyance. Plus, a James Bond Retro-Review of "On Her Majesty's Secret Service"

Elvis (2022, Baz Luhrmann, USA/Australia)

There comes a time in every popular musician’s posthumous life when they’re awarded a Hollywood bio-pic. The staple of the awards season, most of the lauded bio-pics cover historical figures in fields unrelated to the arts. (Last year we had Princess Di, Richard Williams, Tammy Faye, and the Gucci mafia.) The musical bio-pic is quickly turning into the obnoxiously loud—turned up to eleven—stylized floomps of the genre. They demand attention, straighten the naughtiness, and re-package a hyper-meta product that takes on the myth, rather than the artist.

The NC-17 lifestyles of musical artists make adaptations difficult for a wide audience, and not only because of the drugs confusing reality and hyperbole inherent in their own recollections. But in recent years, without the same restrictions from the Production Code that had made them chaste and tame half a century ago, musical bio-pics are becoming hollow shells of PR junk designed to increase the artists’ streaming numbers and sell fan-packed anthologies and merch.

In terms of their plots, they always depict the young, struggling artist crafting their magnus opus under the hindrance of a greedy, outdated, fat manager or record label. Nothing but a dumb, troped-up battle of good v. evil, which unfortunately comes at the expense of the real complexities in the musician’s life. The better stories would be artists v. their art, since that’s the struggle that produced the piece of work that resonated with people. For instance, the writers of Bohemian Rhapsody sanded down the rough edges of Freddie Mercury and Queen into a PG-13 story, when it should’ve been the X-rated cousin of Deep Throat. Instead, we watch a lame (and inaccurate) conflict between Queen and the record label. The producers of the R-rated Rocketman were threatening to pull the same stunt after Rhapsody’s financial whoopty-doo.

At one point in time, films like Walk the Line, I’m Not There, La Vie en Rose could engage with the life of an artist in a serious, artistic manner—without the glammy makeup and blinding lights. Was it Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story that ended this strong outing, or the decade-long shift from independent to corporate filmmaking, the former gasping for air by 2007?

By the time Straight Outta Compton rolled into theaters the following decade, gangsta rappers became all the rage for white affluent liberals. Another instance of legitimate black expression co-opted and mishandled.

A few years later, Mercury’s epic rompings were sanitized for hetero families and Marvelized asexuals. And now this Summer, we’re watching Elvis Presley in his West German barracks fall in love with Priscilla, who was only fourteen years old at the time—but the film doesn’t tell us that of course. An odd detail to leave out, but hey, he couldn’t help falling in love with her.

Baz Luhrmann tells the Baz Luhrmann story of Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis through the oblique fever dream of Elvis Presley’s (played by Austin Butler) manager, Colonel Tom Parker (another Tom, Tom Hanks). The cameras are flapping around at every conceivable angle, the lighting reminds one of those fireworks shows that accidentally light all the fireworks at once, and edits too fast for the audience to understand anything in The King of Rock ‘n’ Roll’s long, yet short-lived life.

Elvis is a classic example of the artist as good v. manager as evil plot, which sidelines the more interesting conflicts in Presley’s life so that we can experience post-Covid Tom Hanks in various continuity error plastic noses and non-comprehensible accents. For as talented as Luhrmann is in commanding a film’s—or just his own—vision, he can’t fix a sub-genre that is creatively dead. In a way, Luhrmann butchered Elvis the same way Parker butchered Elvis.

The plot suffered most from having to stuff the different eras together, from the Hillbilly Cat to Elvis the Pelvis to “the next James Dean.” Although tragically brief, Luhrmann further cuts his life story short by framing the narrative through Parker’s Vegas-tipsy memories. It’s unclear what is true biography and what’s hindsight—made more confusing through the audiovisual editing orgasm that doesn’t allow for rest. Presley’s life has always been a mystery in need of genuine revelations, but Luhrmann opts for keeping him in the obscure, mythical status of mega-celebrity.

(One part worth noting for its wtf-ness: while Col. Parker was with his road troupe, they listened to a young Elvis on the radio who had recently been brewing a storm on local stations. The sound is familiar to their ears as southern, Black music. And then comes the record scratch, followed by the reality that they were, in fact, listening to a white person!!!! **camera zooms and zips, eyes bulge—mine roll—Elvis echoes and intensifies. It’s the type of cringe scene that was already a filmic parody in 1967’s In the Heat of the Night. Mind you, we get this scene, but nothing about his peanut butter and banana sandwich recipe or latrina mortem.)

The best (and only good) part of the film is Austin Butler’s tight-rope performance between replica and essence. He captures the spirit of Elvis Presley, maintains the image, but twists both towards his own characterization. With a different director or script or production, a film like this could’ve easily sent Butler into stardom. But he’ll have to wait for that. There isn’t much to say about Tom Hanks as Tom Parker. They should’ve re-cast the role with someone less famous and de-emphasize his narrative perspective. But when a production is employing the “nicest man in Hollywood,” who is both bankable and recognizable in an industry reliant on those two traits, the film films itself at that point.

Another irksome quality of any bio-pic running through the late sixties is the benign use of the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy (usually not Malcolm X), Altamont, Sharon Tate—Luhrmann squishes the latter two together in the same scene—and others, to provide a way for the protagonist to shed anachronistic crocodile tears, whether true or not. Will Sloan and Luke Savage aren’t incorrect in comparing this farcical use of raw historical moments to the magazine rack at the supermarket checkout line; somehow, it’s always the 50-year anniversary of the moon landing, or The Beatles playing the Ed Sullivan show, or Elvis dying via constipation.

Elvis is currently in theaters. Warner Bros. released the film on June 24th.

(Note: The following is a preview of an upcoming Bond essay, which will cover all twenty-five Bond films, which I recently watched in order.)

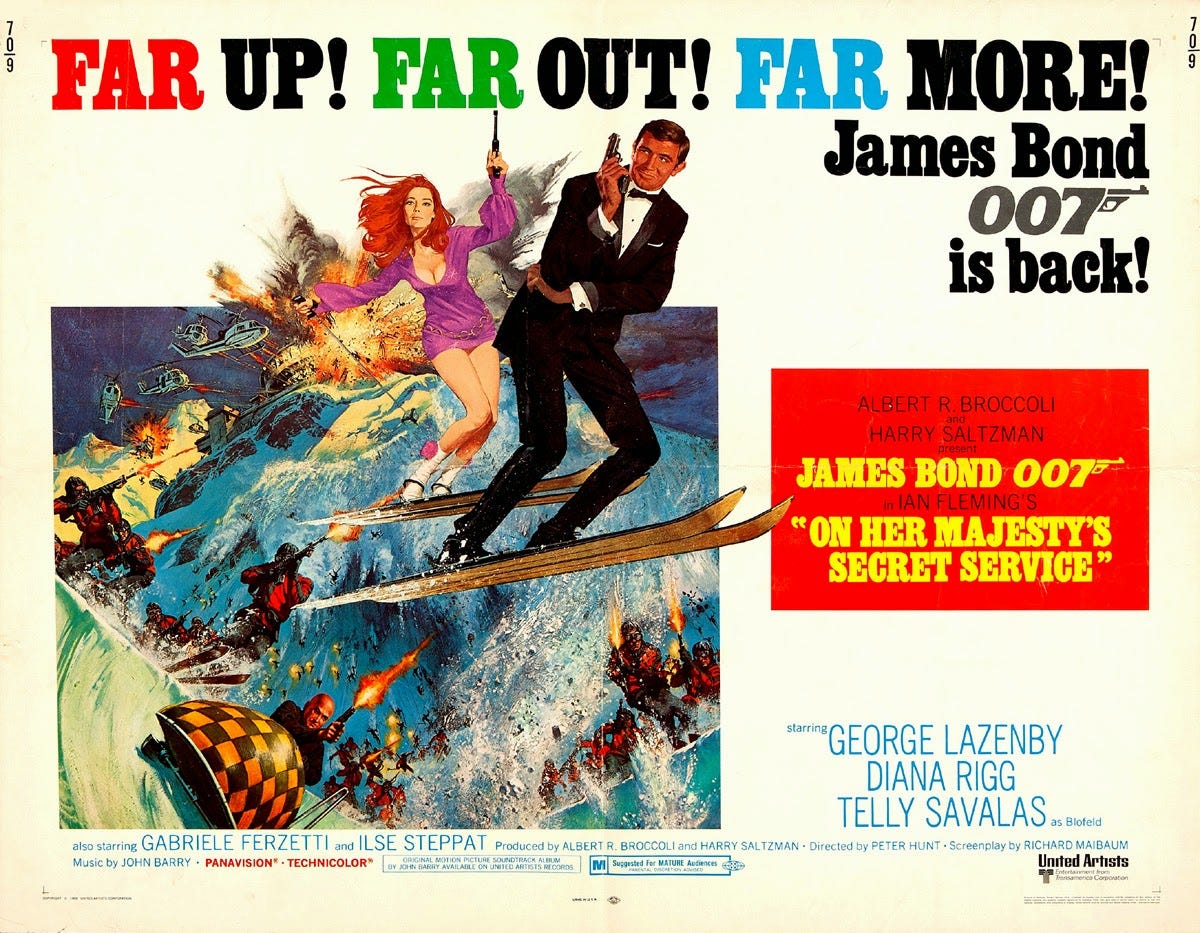

Retro-Review: On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969, Peter R. Hunt, UK/USA)

In heated competition with Skyfall, 1969’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service is the strangest James Bond film. Majesty features Bond at his most vulnerable with a romantic pathos that only came close again in the most recent No Time to Die, but the Majesty had the weightier aspect of being the first non-Sean Connery 007 and become a pivotal re-focusing of the franchise.

Sean Connery played the MI6 agent five times in six years, beginning in 1962’s Dr. No. By the time EON productions released You Only Live Twice in 1967, 007 and James Bond became household names, box office revenues regularly returned over ten times the budget, and a cinematic franchise was born. But all good things must come to an end. Connery had announced his retirement from the role during the production of Twice, which sent the producers scrambling for a replacement. Albert R. Broccoli, the Kevin Feige of the franchise, and Connery were not on speaking terms for the eight-month production.

For Majesty Broccoli and co-producer Harry Saltzman considered over four-hundred actors before settling on an Australian model, George Lazenby, who had only acted in commercials and completely finessed his way into the star role (check out Becoming Bond, streaming on Hulu). The production also turned to a new director, Peter R. Hunt, who had been the editor on all the Bond films. His editing style—adrenalized, smartly paced—would prove extremely useful in re-booting the franchise, which by then was relying more on grander set-pieces with static group fights. Also important was the addition of John Glen, a future Bond director, as editor and second-unit director, who adhered to Hunt’s editing style.

Majesty opens with an audio-visually heightened, surreal at the time, beach sequence where Bond saves Tracy (Diana Rigg) from drowning. Rigg was the first Shakespearean-trained actor to play a Bond girl, who were usually just models, and today is known for playing Olenna Tyrell in Game of Thrones. They picked an experienced actor because in Majesty, her part had a much larger character arc than any other female in the Bond universe, which remained unsurpassed until Léa Seydoux. After saving her, Bond stumbles across a European crime syndicate whose leader is Tracy’s father. He’s concerned for his daughter, so he offers Bond a million pounds to marry her. Being a gentleman-agent, Bond declines but will continue to court her if he helps Bond find Blofeld (played expertly by Telly Savalas), leader of SPECTRE.

To go after Blofeld, Bond attempts to resign from MI6 because M relieved him from the assignment. Bond finds Blofeld through a genealogist that Blofeld hired, which allows Bond the chance to wear a disguise and infiltrate Blofeld’s lair. Hiding out on the top of an alpine peak, Blofeld is running an allergy research clinic that doubles as a disease incubator that hypnotizes young women and uses them to spread biological diseases. Bond blows his cover and has an epic downhill ski chase. While trying to escape through a small ski-town, Bond hits reaches a dead-end. He hangs his head in despair, one of the few moments we’ve seen Bond defeated and vulnerable. But when he lifts his head, he sees Tracy. She helps him escape to an abandoned barn outside of the city where he then proposes to her.

The next day, they’re forced outside, and an avalanche buries Bond allowing Blofeld to capture Tracy. M is prepared to accept Blofeld’s ransom, but Bond mounts a rescue mission assisted by Tracy’s father. In another epic downhill snow chase, this time with bobsleigh, Blofeld crashes out, and his facility is destroyed. The films ends with Bond and Tracy’s wedding with them driving off into oblivion. The end.

Just kidding. During their drive, Blofeld and his henchwoman pull up and spray the Aston Martin DBS with a machine gun, which hits Tracy in the forehead. Holding her in shock, Bond tells a passerby:

It’s all right. It’s quite all right really, she’s having a rest. We’ll be going on soon. There’s no hurry, you see, we have all the time in the world.

The haunting dialogue is identical to the original text in the Ian Fleming book—the only Fleming book I’ve read. I was struck by the book’s sincerity in Bond as the weak romantic rather than the strong philanderer, which wouldn’t have worked with Connery.

George Lazenby, in his first feature film performance, took the Bond role, which was thoroughly embodied by Connery’s spirit and charisma, and made it his own. Reviews in 1969 dismissed Lazenby for his TV commercial background, especially the British press, which for most of the decade had been praising their Scotsman and were unimpressed by the boyish Aussie. Reviews now have retrospectively revived Majesty as a great Bond film—one which you can add to your list of Christmas movies.

In the historical context of the Bond franchise, Majesty and Lazenby performed the vitally important task of re-booting a series stuck with a single actor and increasingly bizarre action gimmicks. Each time Bond becomes a complacent charmer reliant on bigloud scenes, which happens with Roger Moore and Pierce Brosnan, it’s necessary to introduce the palette cleansers of a Timothy Dalton and Daniel Craig, the gloomier, rebellious Bonds that pull the cinematic hero down to our humble level.

Thank you for once again checking out my Substack. Please like it and use the share button to share it. And don’t forget to subscribe to it.