Hemingway’s Iceberg Theory (feat. 'Indian Camp')

What is the Iceberg Theory and how did Ernest Hemingway use it for his fiction?

What is the Iceberg Theory?

Ernest Hemingway only made passing references to his version of the iceberg theory in the first decades of his writing. In 1932, he made his first reference to the theory:

If a writer of prose knows enough about what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of the movement of an ice-berg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.

-Death in the Afternoon

By the 1950s this theory became a formulaic system that provided a sort of theory for the short fiction medium itself. In an interview for The Paris Review, Hemingway states his principle of the iceberg: in terms of conscious knowledge and its utility in the story, Hemingway places “seven-eighths of it underwater for every part that shows.” He argues that the iceberg will be strengthened by the elimination of “anything you know.” Hemingway writes in this rigorous manner to provide an “experience to the reader so that after he or she has read something it will become part of his or her experience and seem to actually have happened."

Several months after the publication of this interview, Hemingway wrote in his memoir, A Moveable Feast, that he omitted the real ending of his short story “Out of Season” on account of his new 'omission theory' whereby “you could omit anything if you knew that you omitted and the omitted part would strengthen the story and make people feel something more than they understood." And finally, Hemingway wrote this theory 'into law' with “The Art of the Short Story,” published posthumously in 1981. In a similar description, he “found to be true [that] if you leave out important things or events that you know about, the story is strengthened…The test of any story is how very good the stuff is that you, not your editors, omit." Because of Hemingway’s reluctance to discuss writing, these descriptions make up his only explicit mentions of the iceberg theory. Appropriately enough, he kept seven-eighths of the theory’s description and implications underwater, which I will illuminate.

According to both Hemingway’s iceberg theory and Suzanne Ferguson’s elliptical-metaphorical plot analysis, short fiction in particular thrives on vital plot details being 'submerged underwater.' That by doing so, meaning needs to be constructed by the reader to make sense of the story, which is not only typical of modernist literature but expands to our general sense-making of the world; the unorganized and non-linear surface events of our lives are only made meaningful if we find connections between those events with deeper level (or subconscious) content. The dignity in the one-eighth of the iceberg above water comes from within the reader.

Hemingway argues that “if a writer stops observing he is finished. But he does not have to observe consciously nor think of how it will be useful. Perhaps that would be true at the beginning. But later everything he sees goes into the great reserve of things he knows or has seen." Is he not here indirectly talking about the subconscious? We observe in order to retain knowledge at a deeper level in the ‘great reserve of things,’ which Hemingway then alludes to when he omits important information in the text. In this way, he is writing in a style that communicates to readers on a deeper level in which they subconsciously fill in the gaps to have an experience that is personal to them but universal in reach. Giger argues that “it is this common ground of universal, archetypal emotions, emotions evoked through symbols requiring no special literary or cultural equipment, that the iceberg – in theory and in practice – has been erected."

Iceberg Theory Case Study: “Indian Camp"

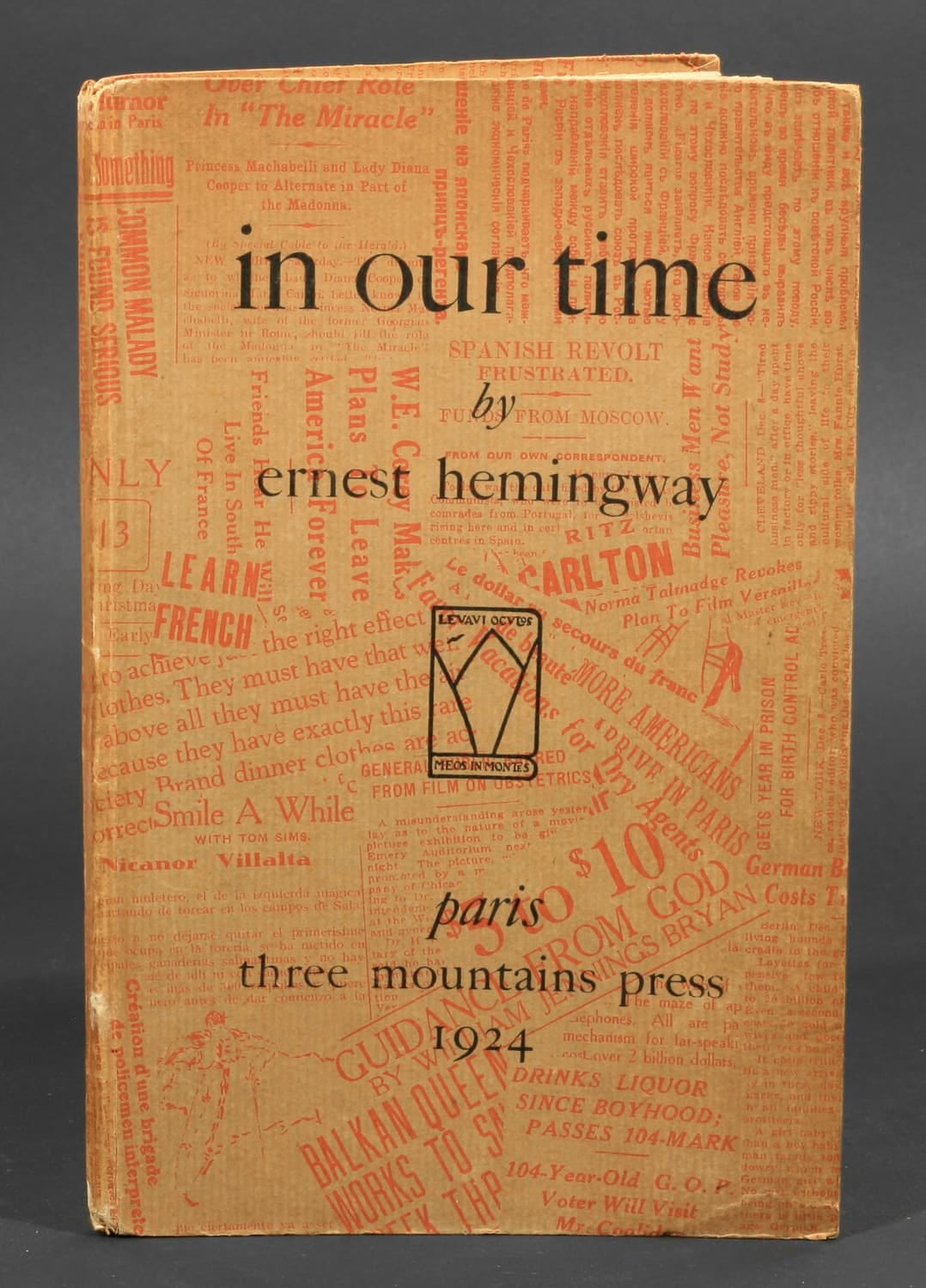

In a letter to F. Scott Fitzgerald after the publication of the short story collection In our Time, Hemingway rated “Indian Camp” as one of the two best stories in it because it “alludes to something left out." Hemingway deleted nearly the first half of the original story, which was later published as a separate story. In the subsequently shorter, published plot of “Indian Camp,” a young Nick goes to an Indian camp with his father and uncle so that his father, a doctor, can deliver the baby of an Indian woman. Once completed, they leave the camp. This arrival to birth to departure amounts to the entire plot arc, which then becomes elliptical when Hemingway omits the first half of the story about days leading up to the birth, any context about the Indians, the birthing procedure, the unexpected death of the Indian father, and Nick’s reaction to much of the events.

Two omitted moments within “Indian Camp” are specifically important to mention, first the birth itself and then the death of the Indian father. Both happen away from the narration and are the moments in which the debate among commentators reach their most disparate. The birth is the main driving force of the plot, it’s what necessitates the Adams presence and once ‘completed’ sends them back across the lake to their own camp. Little detail is revealed in the narration dramatizing the birth; the procedure itself includes a single paragraph in which the mother bites the Uncle, whom then calls her a “squaw bitch,” then only, “Nick held the basin for his father. It all took a long time." “It” is used to describe the entirety of a dangerous and highly dramatic caesarian-section done with only “a jackknife and sewing it up with nine-foot, tapered gut leaders." So why does the narration fail to explicitly play out the main plot point? This elliptical plot leaves the reader speculating not just on the procedure, but also young Nick’s reaction to assisting in a violent medical act and the mother’s health.

After the operation, Nick’s father is ecstatic from his perceived success while Nick “was looking away” and “didn’t look at” something his father removed from the mother and put into the basin because “his curiosity had been gone for a long time." Clearly a change in Nick’s behavior happened during the operation; in contrast during pre-operation, Nick was concerned about the mother screaming and “watched his father’s hands scrubbing each other with the soap." The mother, besides screaming in the beginning and then biting Uncle George during the procedure, remains a passive subject in the narration. Even Nick’s father explains that “her screams are not important. I don’t hear them because they are not important." While Nick’s father is celebrating post-operation, the only narration about the mother describes her as being “quiet,” with “her eyes…closed,” looking “very pale” and “not [knowing] what had become of the baby or anything." Though taken out of their original context, these narrative moments are all that’s given about Nick and the mother immediately before and after the procedure.

The operation was likely left out because, according to Hemingway’s theory, all irrelevant information towards conveying the experience needs to be omitted to enhance the iceberg. Left to the imagination, giving birth is something violently ‘known’ within the subconscious of most people, and by leaving it to the reader, it then makes them consciously formulate the experience in order to make sense of the changes in not just the mother and Nick, but also Nick’s father. This conscious rendering forces the reader to experience the suffering of the two, an implicit empathizing, that the reader then must use to make sense of the disconnected pre- and post-operation plot points. In a seemingly strange formulation, omitting conscious information helps connect reader and writer closer together, which in a short story is vital to conveying an affective experience with brevity.

The second moment of the story likewise happens away from the narration, but this time revealed unexpectedly and beyond the control of Nick’s father. While still exalted from the operation, Nick’s father wants to check on the new father, whom was confined to the upper bunk in the bed because “he had cut his foot very badly with an ax three days before." The only other instance where the Indian father is mentioned is when he “rolled over against the wall” during pre-operation. Then comes the shock when Nick’s father “pulled back the blanket from the Indian’s head. His hand came away wet…His throat had been cut from ear to ear. The blood had flowed down into a pool where his body sagged the bunk…The open razor lay, edge up, in the blankets.” Before his father could take him away, Nick “had a good view." And in only three short paragraphs this information is delivered before switching scenes to their walk back to the boats. Between the pre- and immediate post-operation, it is assumed that the Indian father slit his own throat with the razor blade, and again, the reader is left curious as to why the father may have commit suicide.

The omission of the death scene and shock of the reveal, to both the reader and the Adams, led to interpretations of the connection to the violent birth by way of hypothetical plot construction. But instead of the hypothetical plot connecting the elliptical plot points, commentators have relied on explaining the death as metaphorical. This is partly because the death has no clear narrative preparation, but also because its explanation is traced back to the omitted process of the birth. The narration reveals to the audience that the mother requires a special birth while the cause of the death remains open-ended, hence the shock of its reveal. The biggest difference with the revealed death being is that the analyses are metaphorical: the doctor’s blindness symbolically killed the father. And because so little of the death of the Indian is revealed in the narration, the iceberg is strengthened in forcing the readers to endow meaning and empathize with the Indian father’s probable suffering as strange and foreign men operate on his screaming wife.

Though I’ve been examining the iceberg theory as it relates to short fiction, it can nonetheless apply to novels. For instance, in the Hemingway interview mentioned previously, he uses The Old Man and the Sea as an example of a text that would have been “over a thousand pages long” if not for his theory. But the iceberg theory is more important for short fiction because of the limitations imposed on its length. In a condensed amount of space, a short story needs to convey an experience without the use of development. The iceberg theory isn’t only important because of its applicability to writing an affective short story. Its significance relates to a deeper understanding of empathy, meaning, and art’s facilitation in that process.

For Hemingway, the iceberg is a philosophy disguised as a literary theory. For the reader, Hemingway presented a story that mirrors the process in which we make sense of a disconnected reality. The importance in learning and then applying this process is then a liberating tool that the individual can utilize to improve their life; one which helps us better empathize, communicate, and live more openly and compassionately. The dignity of the iceberg is the dignity of finding meaning in one’s life.

"Indian Camp" was originally published in Transatlantic Review in 1924.

Edited: 19 March 2021, 2 July 2022.