Trouble in Censoring: Lubitsch v. Hollywood?

The Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) was founded in 1922 as a trade association by the Hollywood studios in order to protect their interests. Because of the increasing concern over government control by government regulation and influential religious leaders organizing mass boycotts, the MPPDA published the Motion Picture Production Code in 1930, which was a loose, self-regulating guideline of what content was allowed to be depicted in films. Because of its relative ineffectiveness in stopping external pressures from threatening the industry after the Code’s publication, the MPPDA then established the Production Code Administration (PCA) in 1934 to rigidly enforce the Code. Although only a list of things not allowed so as not to offend the audience or lower their moral standards (e.g. murder presented in an uninspiring way, upholding sanctity of marriage, etc.), it had further implications in terms of social control, representation of content, and knowledge of the audience.

Of importance here is the Code’s ability in determining what content is appropriate or not, and who exactly has that arbitrary authority. In Richard Maltby's chapter on the Code from Grand Design, he explains the importance introduction of "textual indeterminacy," which granted permission by the Code in swimming the gray waters of explicit content portrayed implicitly. That rather than limiting Ernst Lubitsch’s career and artistic expressions, known in the pre-Code industry as having greater use of sexual humor via film, the Code created a necessity of change that advanced and refined his distinct style through the execution and collusion of textual indeterminacy.

Textual Indeterminacy

Taking a short litero-theoretical direction in explaining textual indeterminacy, it has two camps in which it plants its roots. The first, which is applied in literary studies, is the “element of text that requires readers to decide on its meaning.” The second is connected to the deconstructionism of Jacques Derrida, which is the “uncertainty invoked to deny final meaning…that there is no final arbiter of deciding the meaning.” The literary definition is useful in discussing the relationship between the text, in this case the film, with the audience: because of a film’s use of audio and video, a multiplicity of actions are produced at the same time, which creates manifold meanings when combined. The audience then takes in the scene and constructs meanings from what is given, which in a dual-sensory medium like film can have conflicting and mutually exclusive outcomes.

The deconstructionist definition is useful in illustrating the relationship between Lubitsch and those in control of his film’s production/distribution (in this case studio heads and the PCA). Although not as useful as the literary definition, to deny final meaning and an arbiter’s ability therewith places Lubitsch in a more privileged position of control over his films’ meanings, in theory, compared to his studio bosses and heads of the PCA. In other words, Lubitsch as filmmaker produced the multiplicity of meanings in his films and those with final control of how that film will be distributed and exhibited, according to deconstructionist-indeterminacy, don’t have the ability to truly decide on its meaning. Instead that authority lies with the audience (the eye of the beholder...).

Indeterminacy became a more discussed literary term after the famous Polish phenomenologist, Roman Ingarden, published The Literary Work of Art (1931) and was translated into English. In this influential early text on literary theory, he writes that “it is always as if a beam of light were illuminating a part of a region, the remainder of which disappears in an indeterminate cloud but is still there in its indeterminacy.” By “part of a region” Ingarden is talking about objects contained within a text grouped together, which produce many meanings but without sharply drawn borders. And without noticeable borders, the existence of the “indeterminate cloud” makes the finality of meaning difficult to locate. Literary theorists since then have used Ingarden’s initial investigation in indeterminacy to connect it to the reader’s role in producing meaning.

Maltby finds that the implementation of the Code and its insistence requiring films to present proper moral values was, in fact, assisting rather than inhibiting the ability for the viewer to construct meaning. The viewer is therefore peering into Ingarden’s ‘indeterminate cloud’ each time the ‘beam of light’ is unambiguously showing only moral values. And because of this, as Maltby argues that “textual indeterminacy became a feature of Hollywood’s representation of sexuality, emerging in complex and oblique codes that resembled neurotic symptoms or fetishes.” Although just one of many censored topics, sexuality was a particularly taboo subject in conservative 1930s America. Therefore, the PCA was forced to censor amoral sexuality. Subsequently there began a form of representation in which the audience was forced to find meanings through “a game of double entendre.”

The multiplicity of viewings inherent in an audience made it particularly difficult for the PCA’s ability to control content. Therefore, the Code enabled this multiplicity to exist by finding “ways of appealing to both ‘innocent’ and ‘sophisticated’ sensibilities” only “once the limits of explicit ‘sophistication’ had been established.” This way the industry was able to maintain a level of plausible deniability while maximizing the multiplicity of viewings, thus appealing to a larger market of viewers. On the surface of the film’s content, the PCA was able to appeal to the “innocent” audiences and retain their commitment to those values, but still allow the “sophisticated” viewers to look into the ‘indeterminate cloud’ that the PCA could deny existed. This relates back to the literary theorists’ arguments of the prime importance for the audience in actualizing the meaning of the text, which the PCA seemed to recognized. Rather than just censoring and hindering films, “it operated, however perversely, as an enabling mechanism at the same time that it was a repressive one.”

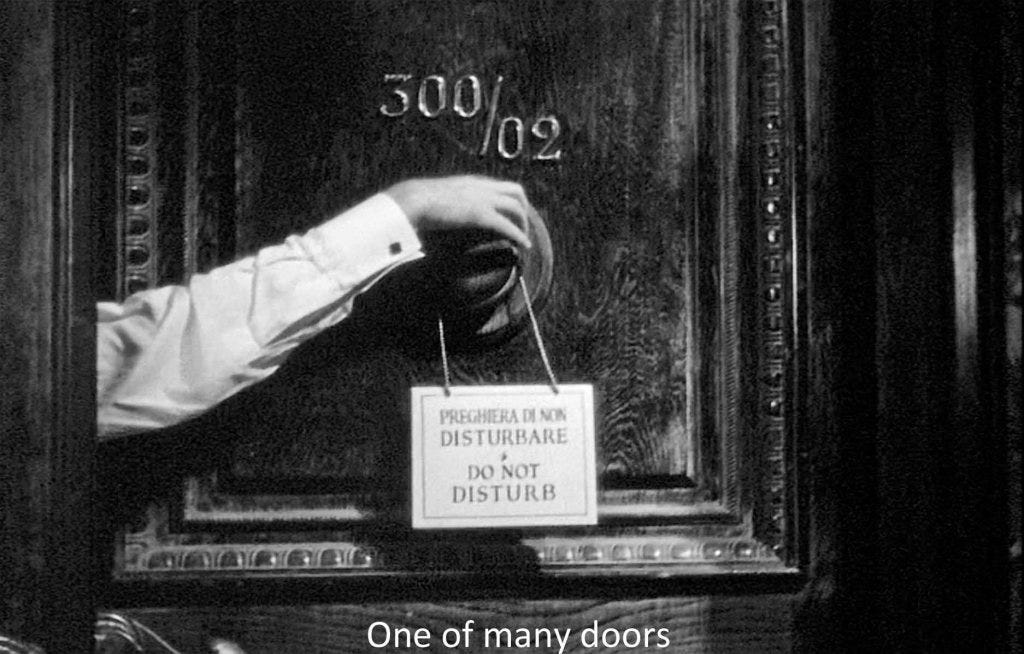

Ernst Lubitsch and Erotic Doors

Ernst Lubitsch was born in Berlin and moved to Hollywood when he was 30 years old in 1922, the same year the MPPDA was established. Early in his Hollywood career, the ‘Lubitsch Touch’ became a popular term in the industry and among critics describing his unique style, which can be summarized as a mix between salutary mockery, anti-sentimentalism, and use of visual comments for “condensing into one swift, deft moment the crystallization of a scene or even the entire theme.” Lubitsch would noticeably utilize a certain camera movement or set piece as a metaphor to mock a particular sentimental issue, which for him was sexuality much of the time. This topic was important to both Lubitsch, in his representation of it on screen, and the PCA, which attempted to control it. According to Herman G. Weinberg’s monograph on Lubitsch, because Americans had taboos of and publicly repressed the subject of sex, Lubitsch “became facetious on the subject and decided to make American audiences laugh at something they took so seriously.” Therefore, it appears that the topic Lubitsch liked to represent in his films with his unique style was also one of the most regulated subjects by the PCA. But as Weinberg explains, even though sex was the obsession for most of Lubitsch’s characters, he never had a problem with the censors during his career. This is only half true; many of Lubitsch’s characters certainly obsessed about sex in one form or another, but it did lead to censorship by the PCA in due course.

Lubitsch’s style had a special resonance with the audience and their ability in constructing meaning from the content. In a news article from 1937 describing a scene from his film Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife (1938), in which a couple angrily enters a bedroom and cuts via dissolve to them dancing romantically, Lubitsch said that he has “confidence in the intelligence of audiences…I’ll let the audience figure out for themselves what happened behind the closed door, and only show the result.” The door is used many times in Lubitsch’s films as a way of showing without directly telling. James Harvey finds that Lubitsch and co-screenwriter Samson Raphaelson “set out to test the expressive limits of indirection—to make those closed Lubitsch doors achieve a kind of maximum eloquence. As a result…our own responses become the subject of the film.” Because of the closed doors blocking the audiences’ direct participation with the action of the characters, the audience is forced to construct meanings as suggested from the mood of the characters and tone of the scene before and after the door is closed. Scott Eyman refers to this style as a process of omission and commission in his Lubitsch biography: “what is unsaid, what is unshown.” Indirection or omission was a form in which Lubitsch allowed the audience a freedom to interpret and concretize meaning from the content, which was appealing in its application as proven by his popularity.

Nora Henry in her book on German directors claims that Lubitsch “chose comedy as primary means of his artistic expression because he was a moralist…he appealed to the viewers’ intelligence, allowing them to draw their own conclusions” by showing them complex characters. Henry also indicates this indirection and elliptical style was best for Lubitsch in specifically communicating humor and wit to the viewer. In Joseph McBride's excellent Lubitsch biography, he concurrently argues that Lubitsch respected the audience’s intelligence by allowing them to participate in the closing of ellipses. The problem that then arises is when the PCA arbitrates the ‘beam of light’ and indeterminacy that is so important to Lubitsch’s style and subsequent popularity. So how did Lubitsch get away with representing and suggesting sexuality in his popular films?

Weinberg, although not accurate in his research on Lubitsch’s censored films, writes that he “was too sly for the censors and outwitted them at their own game.” One reason for this slyness was because of his Touch, which in its mockery of taboo subjects still maintained an important level of confidence and satire. According to Harvey, this ability to outwit the censors by getting away with “really dirty jokes” was appreciated by many in the industry under the same constraints. McBride thinks that Lubitsch didn’t necessarily outwit the censors, but rather that the censors “knew what Lubitsch was saying, but they couldn’t figure out how he was saying it, so they usually had to leave his scenes uncut.” For this reason Lubitsch was able to flourish despite censorship and hide “in plain sight but always with a sly, self-protective deniability.” In David Kalat’s counter-history on classical Hollywood comedy, he writes that Lubitsch “spat in the faces of self-appointed censors trying to impose their Puritan preoccupations on the nation’s popular culture.” Like McBride’s line of argument, Kalat agrees that the censors had a difficult time finding what exactly to censor, but argues further that Lubitsch avoided censorship because of economics. That because Lubitsch’s films made money (but not all of them), and that his use of indirection always made sure the targets were barely missed, censors threw up their hands in defeat. This is an important point that relates back to the PCA’s ability in invoking plausible deniability when it came to representations for different sensibilities: the PCA wasn’t blind when it came to indeterminacy, that they actually used it for economic gain by maximizing audience size. After all, the PCA was a subsidiary of the MPPDA, the latter being an in-house, self-regulating trade organization that cared mostly about protecting their interests rather than what really happens behind Lubitsch’s closed doors.

By way of illustrating Lubitsch's style vis-à-vis textual indeterminacy, his two big films from the early 1930s provide clues.

Pre-Code Lubitsch

Trouble in Paradise was released only a few years after the market crash in 1929, in which the nation was in the midst of the Great Depression following the ‘Roaring Twenties.’ In the 1930s, American society experienced a “turning-in-on-itself, a self-absorption to replace the extreme self-criticism of the twenties.” And because of this change, films of the 1930s in general tended to emphasize American rather than European culture. Also important was the introduction of the Code in 1930, which wasn’t rigidly enforced when Trouble was produced and released, but still reflected a changing society moving in a certain moral direction.

Film summary: a pair of jewel thieves (Gaston and Lilly, played by Herbert Marshall and Miriam Hopkins, respectively) fall in love because of their mutual satisfaction in their partners’ ability in theft. In one of their bigger ploys, they plan on scamming a wealthy owner (Madame Mariette Colet played by Kay Francis) of a perfume company. Gaston is able to influence his way into being the trusted secretary and suggested lover of Madame Colet, who also has multiple other suitors, but is found out when one of her suitors recognizes Gaston. In the climax, Madame Colet finds out the truth of Gaston and Lily but lets them go. And in the final scene, Gaston and Lily embrace after finding out they both stole the necklace that Lily wanted, Gaston from Madame Colet and Lily from Gaston, and ride off happily together.

Immediately from the summary of the plot, multiple topics that censors commonly regulated were prominently used: adultery, criminal theft, identity fraud, and promiscuity. In this way, and because it came out prior to the creation of the PCA, Trouble is a pre-Code film for its use of amoral subject matter. In section I, subsection 1 of the Code, it states that “Methods of Crime should not be explicitly presented,” which includes “theft, robbery, safe-cracking…should not be detailed in method.” In general the Code wanted to make sure the representation of crime was treated without sympathy so that it wouldn’t inspire the audience to commit the same acts. Although it appears after the fact that such a restriction shows a certain ignorance from the censors in how the audience will respond to depictions of crime, it actually shows a deeper understanding the censors had about the connection between cinema and the public. In the preamble to the Code, they indicate that producers are responsible to a trusting public and recognizes that films, as primarily entertainment, still have a level of propaganda in influencing the viewer towards different meanings. Here the Code is indirectly acknowledging Ingarden’s ‘beam of light,’ which are the moral standards that should be upheld on screen, and ‘indeterminate cloud,’ which is the potential for audience’s to interpret amoral standards.

In the final scene of Trouble, Gaston and Lily succeed in stealing Madame Colet’s money from her safe and necklace, then ride off together happily in love. As Maltby interprets the Code and PCA president Joseph Breen’s understanding of it, he finds that the “compensating moral values” stipulation created “a calculus of retribution or coincidence [that] would invariably be deployed to punish the guilty or declare sympathetic characters innocent.” Between the publication of the Code in 1930 and actualized enforcement of the PCA in 1934, the final scene of Trouble presents an interesting case in showing the influence of the PCA because when the film was being reviewed by censors in 1935 for a theatrical reissue, it was denied a release certificate and wasn’t officially released again until 1968 when the Code was repealed. As Eyman indicates, because Trouble was released soon before the Code’s enforcement, it was able to get away with a “story centering on sexual swapping and resolutely unpunished crime.” And because the entire plot revolves around Gaston and Lily’s thieving deception of Madame Colet, no single shot or scene could be censored to promote the values of the Code. Instead, the whole film would need to be banned. In William Paul’s biography, he writes that from 1932 to 1933 more “salacious subject matter” was used to attract audiences in the midst of the Great Depression. Therefore, a tentative conclusion can be drawn to confirm the MPPDA’s self-regulating as mostly economic rather than censorious of content, and also Lubitsch as money-maker being able to get away with risqué content (at least until 1934).

Trouble and the early 1930s was the beginning of a turning point in Lubitsch’s style and career. The Great Depression lowered the filmgoing audience and box office receipts of studios, which along with expensive films that didn’t recoup costs led to Paramount, Lubitsch’s studio, to decline into receivership in 1935. For this reason, as both McBride and Paul argue, Lubitsch was able to present a crime story with a socio-cultural dimension as opposed to the fantastical musicals that preceded it. Although the protagonists of Trouble are playing upper class Europeans, American audiences desperate for jobs/pay could understand the function of stealing from the rich, even though no Robin Hood ending transferred the riches to the needy. In this way, audiences would certainly sympathize with criminal activity, which in 1932 was not allowed under the then un-enforced Code. But as mentioned just above, that would soon come under pressure only a few years later.

Mid-Code Lubitsch

On July 1, 1934 the PCA officially began enforcing the Code after further external pressures from religious groups and government agencies complained that the Code was failing to be implemented by the MPPDA (as is obvious with Trouble being released without, may I use the word?, trouble). Although The Merry Widow was released in October of this year, Lubitsch was in the middle of production when the PCA began its work. The new president of the PCA, Joseph Breen, warned against some risqué shots in the script, then along with every State censorship board approved the completed film. At the premiere of the film, MPPDA president Will Hays and influential magazine editor Martin Quigley (co-author of the Code and facilitator of catholic influence on it) were enraged that Breen gave it a seal of approval. After Breen was summoned to New York from Los Angeles and had a lengthy negotiation with Hays and religious leaders, they agreed on censoring material before the imminent theatrical release. Although Breen didn’t see the film as amoral, the experience hardened his position as new head-censor.

Film summary: the plot of Merry revolves around a philanderer, Captain Danilo (played by Maurice Chevalier), and a rich widow, Madame Sonia (played by Jeanette MacDonald). After Madame Sonia leaves the fictional kingdom of Marshovia for Paris, the King is worried that the country will go bankrupt because of her vast fortune being carted away. Therefore, the King and Queen devise a plan to send Danilo to Paris to marry Madame Sonia, then have them return to Marshovia. Danilo, a frequent patron of Maxim’s gentleman club, meets Madame Sonia in disguise and falls for her because she’s the only woman who doesn’t respond to him with affection. After games of shifting identities and sexuality, Danilo fails to marry her and is jailed back in Marshovia. But in the end Madame Sonia visits him in his cell and they spontaneously marry.

Hays and Quigley in particular objected to Maxim’s being represented too explicitly a whorehouse and Danilo’s portrayal as a philandering playboy. They didn’t directly object to Danilo’s preoccupation with sex, but rather his care-free attitude towards it not being explicitly immoral. Before with Trouble, Lubitsch was able to get away with a triangular, adulterous relationship revolving around criminal acts, but now with a strong censorship campaign in place, every level of production from the script to the negative film print would be combed over for Code misdemeanors. Merry therefore presents an interesting case because the script was changed only to a minor degree by suggestions from Breen, thanks to producer Irving Thalberg’s support for the script. But by the time theatrical prints were made months later, the pre-Code film was caught up in the beginnings of a decades long campaign to control the production and audience reception of films.

Post-Code Lubitsch

Far from being having no troubles with censors, as Weinberg alleges, Lubitsch’s experiences with the PCA and their censorship campaign had a major impact on his career and filmmaking style. The Catholic Legion of Decency (CLD), founded in 1933 and worked alongside the PCA in issuing seals of approval for films and also helped install Breen as PCA head, first targeted Lubitsch’s Design For Living (1933) and Merry as containing examples of lewd, amoral representations on screen. Then years later the PCA and CLD failed to give seals for several theatrical reissues of pre-Code Lubitsch films, like Trouble. This seemed to have an existential impact on Lubitsch’s career as a filmmaker, as he indicated in an interview in 1934 where he spoke out against the censorship campaign in hindering creative expression and freedom (which no doubt was partially born out of taking tabs of what was happening back in his home country at the time). Lubitsch said that “this present campaign, I must admit, has caused me to worry about the future…If I were to film my old picture, The Patriot, today, it would be impossible for me to make it true to life as I see it. I would be in trouble at once.”

Another factor for the change in Lubitsch’s career was the changing attitude of filmgoers, which in the early-to-mid 1930s was moving in a conservative direction and were more interested in middle-class American representations and the “common-man” style of, for example, Frank Capra comedies. The upper-class ‘comedy of manners’ from Lubitsch primarily set in Europe were less interesting, as the box office failure of Merry and others indicates. When Lubitsch made the unexpected shift to the head of production of Paramount in 1935, he was then able to re-evaluate his position in the filmmaking industry regarding both the external threats of censorship and changing market of taste from the audience. Kalat calls this transition from being censored to the head of production at a major studio as Lubitsch ‘conquering’ Hollywood. So instead of being the decline of his career and filmmaking style, Lubitsch continued making films thereafter according to the new rules.

In writing about the two changes in Lubitsch’s style, Henry credits Chaplin’s A Woman of Paris (1923) as helping Lubitsch appeal to an American audience and the Code, which further refined his Touch even before it was formally adopted in 1930. Moreover, Henry finds that the Code and prevailing taste of the audience were impediments that actually “advanced the development of his style.” McBride likewise agrees that Lubitsch’s films flourished under the Code because it forced obliqueness, which was the style Lubitsch already perfected throughout his German and early American filmmaking career. Although direct censorship was a problem for creative expression, in turn it also presented an opportunity to force more creativity from writers and directors by making them find ways of representing taboo subjects that speaks indirectly to the audience as guided by the Code and censor’s allowance for indeterminacy. McBride’s final point on the matter is that “the Code, ironically, was a leavening, humanizing influence because it forced filmmakers to point their stories toward happy endings. Even if those sometimes seem forced…the strictures under which Lubitsch operated offered a form of checks and balances, an anchoring in traditionalism that he brilliantly counterbalanced with this satire of social conventions.” For example, the ‘happy ending’ of Merry in which Danilo and Madame Sonia get married is anything but middle-class, traditionally happy: the couple are locked in a jail cell by the King, whereby they’re tricked into falling for each other through trap doors begetting alcohol and an engagement ring. Although Danilo leaves his playboy life and settles down, a middle-class ideal, he does so reluctantly and with a touch of insincerity.

Reverent Lubitsch-fan Slavoj Žižek makes an interesting argument about Lubitsch and the Code by arguing, “isn’t Lubitsch’s indirectness also conditioned by the Hays Code censorship?” The Code forced an elliptical way in representing sexual activities, which, for example, in classical Hollywood films was done through fades or dissolves showing a couple going into then out of a bedroom as discussed before. This construction creates two mutually explicit meanings through using certain codified signals (e.g., change of mood, smoking a cigarette, lounging on the bed, etc.), which indicates either the couple did or didn’t have sex. The audience can therefore interpret either one according to their own sensibility, and also it allows the censors and producers to invoke plausible deniability. As Žižek claims, this is the ideology of classical Hollywood, in which “nothing is totally repressed, everything can be unambiguously signaled in a codified way.” In other words, there always exists an ‘indeterminate cloud’ alongside the ‘beam of light.’ Regarding Lubitsch, Žižek argues that his indirection doesn’t give precise codes signaling actions behind the door, which makes the classic Lubitsch Touch avoid the excess of directly confronting codified signals that suggests obscene sexual activity. This then gives Lubitsch a further distancing from the censors ability in locating exactly where the lewd or risqué action is because it isn’t directly signaled. Therefore, the real Lubitsch Touch emerged after maturing in the post-Code era because of the Code’s expulsion of previously codified obscenities from his pre-Code films. The censors failed to know how to censor post-Code Lubitsch movies precisely because the ‘indeterminate cloud’ was never explicitly presented; that was the job of the audience.

Although Trouble is regarded by most, and Lubitsch himself, as his finest film, most of his critically acclaimed films would be released in the post-Code era: Ninotchka in 1939 (familiar to many Žižek readers), To Be or Not Be in 1942, and Heaven Can Wait in 1943, which tentatively shows that the Code more than not benefited Lubitsch’s legacy.

Further Reading on Lubitsch, Hollywood, etc.

Grand Design: Hollywood as a Modern Business Enterprise, 1930-1939, edited by Charles Harpole

Hollywood Censored: Morality Codes, Catholics, and the Movies, by Gregory Black

Ernst Lubitsch: Laughter in Paradise, by Scott Eyman

Romantic Comedy in Hollywood: From Lubitsch to Sturges, by James Harvey

Ethics and Social Criticism in the Hollywood Films of Erich von Stroheim, Ernst Lubitsch, and Billy Wilder, by Nora Henry

The Literary Work of Art, by Roman Ingarden

The Rise of The American Film: A Critical History, by Lewis Jacobs

Too Funny for Words: A Contrarian History of American Screen Comedy from Silent Slapstick to Screwball, by David Kalat

How Did Lubitsch Do It? by Joseph McBride

Ernst Lubitsch’s American Comedy, by William Paul

The Lubitsch Touch: A Critical Study, by Herman G. Weinberg

Like a Thief in Broad Daylight: Power in the Era of Post-Humanity, by Slavoj Žižek