Munich Filmfest (2023) Reviews Part Two, Weekly Reel #56

Monster, Brother, Salty Water, When you Finish Saving the World, Dalíland, The Edge of the Blade, Dead Girls Dancing, A Respectable Woman, The Kombinant, and Boyz

News of the Week: like part one, I can’t recommend anything for Watch Now, but have provided a two-level Save for Later section to parse out those worth watching right when they come out versus saving for a little bit later. The list of films is in descending order based on my ratings.

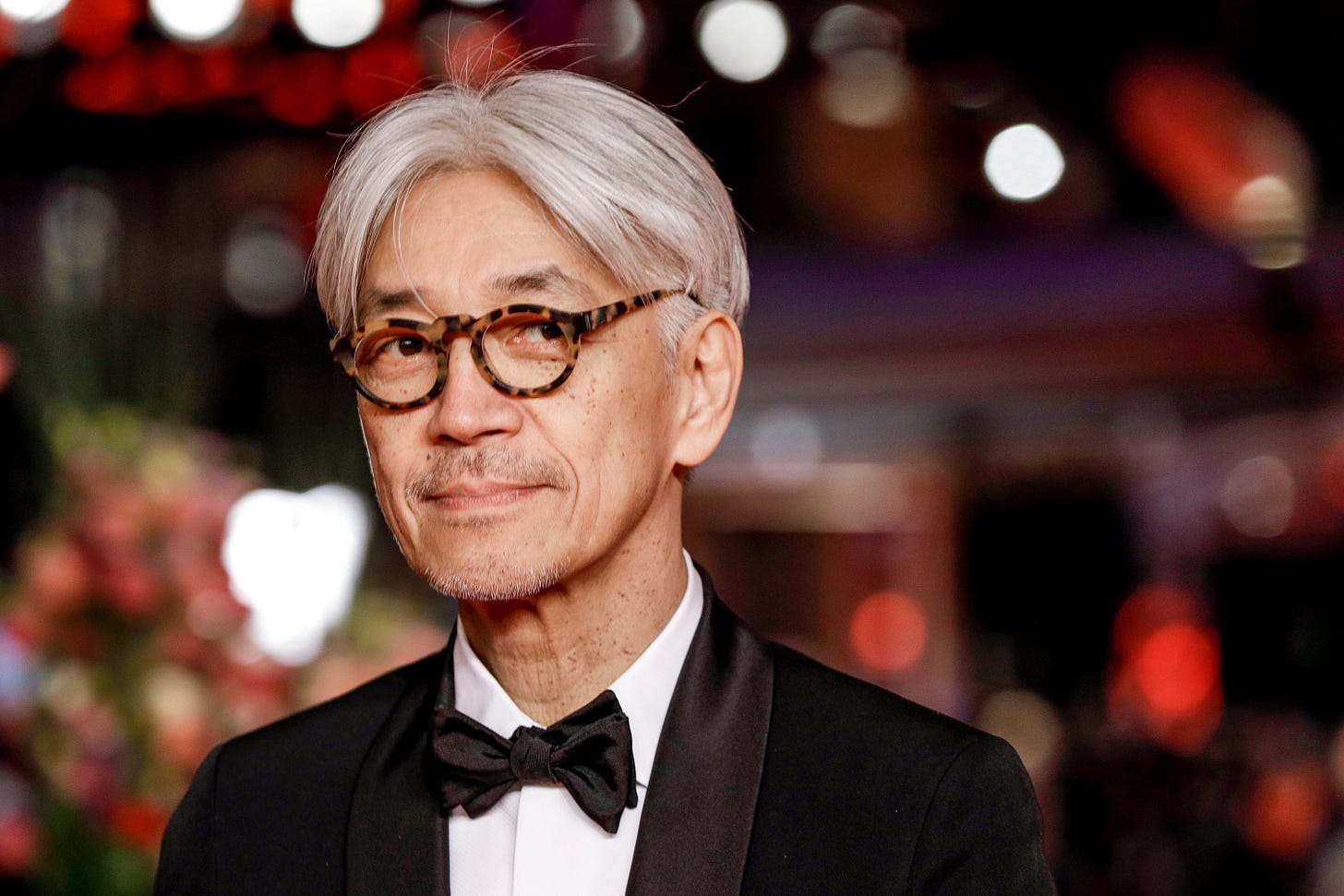

Late but relevant to this WR, big RIP to Ryuichi Sakamoto, a Mount Rushmore film score composer.

Save for Later

Monster (2023, Kore-eda Hirokazu, Japan) is the latest festival-favorite Kore-eda release, following last year’s Broker at Cannes (where its lead, the immortal Korean GOAT, Song Kang-ho, picked up Best Actor) and 2019’s Palme d’Or winner Shoplifters. Though not associated with his films like Godard and Tarantino, a band of outsiders is the unifying theme of Kore-eda films. But in Monster, he veers off course, behind Yûji Sakamoto’s Cannes-winning screenplay, Kore-eda’s first time using another writer’s script in twenty-eight years, to create a social drama that for the first ninety-minutes makes you forget that the film also won the Queer Palm. (Okay that’s all the Cannes references.) The narrative peripeteia after act two hits so hard that the audience forgets who the monster may be, or if there was one at all.

The plot follows a Rashomonesque perspective shift of the same events told from three perspectives. Each anagnorisis compounds until we’re left holding a beautiful flower of filmmaking that puts the usual conventions of blame and finger-pointing to shame. The first two cynosures, Saori Mugino (Sakura Andō), a single mother, and Michitoshi Hori (Eita Nagayama), the homeroom teacher, tell their side of the story about what happened with Minato, Saori’s son, who behaves stranger than usual. Saori thinks that Michitoshi has been physically and emotionally abusive to her son, which is backed up by Yori, Minato’s classmate. For part one, we watch Saori try to find the underlying cause of the issue, especially after the bureaucratic malfeasance of the school’s overly polite, PR-led school administration. For the second part, we rewind and start again from Michitoshi’s position, showing the missing half to the story, which, in any other film, would’ve created a pleasing film after a non-botched climax. But not Kore-eda.

Kore-eda wanted Ryuichi Sakamoto for the soundtrack, but he was too sick to complete the entire setlist. Sakamoto submitted two piano scores, which were stitched together with his previous music, to create another one of his greatest soundtracks of all time and cement his legacy. Sakamoto died less than two months before Monster’s Cannes premiere.

The two children in the film, Minato and Yori, are (*spoilers*) the real protagonists of the film. Their perspective in the third act not only negates almost everything we’ve seen up until that point, but also argues the age-old “adults don’t understand anything.” For all their chinwag and earnestness, they forget who the real victims are—a nice metaphor for all of us, now, today. Their selfless maneuvers are ugly systems of narcissism. But once we break free of that, which Kore-eda directs brilliantly, the pearl of truth reveals itself and will, whenever released, lead to better perspectives on what it means when we’re hiding behind the cover of “protecting our children.”

Monster is a theatrical must-watch, no current release information though.

Brother (2022, Clement Virgo, Canada) begins and ends with brothers Francis (Aaron Pierre) and Michael (Lamar Johnson) climbing a giant electrical tower Metaphor in the Scarborough district of Toronto. Although the story revolves around this moment in time by plus/minus ten years, we watch the two trying to navigate high-school in 1991, where hip-hop is becoming a mainstay and neighborhood violence sends stray bullets into children’s bedrooms. Francis and Michael have a Jamaican-born single-mother (Marsha Stephanie Blake) with an absent father (potentially still around the city). Virgo crafts a beautifully melancholy story about loss and family connected to ethnic strife, which one can’t help but compare to the gentle heartbreak of a Barry Jenkins film.

In an ensemble of excellent actors, Aaron Pierre as Francis so easily shines above the rest that you can’t even tell when his English accent seeps into his Canadian dialect. He plays the older brother, scarred by the place he’s in but unable to leave. He wants to be the next Dr. Dre, but his circumstances—familial, socioeconomic, sexual—conspires against his ascent. He’s tall, broad, imposing, unlike his younger brother, who’s meek. Michael lacks the same charisma, and even when Francis is out of the picture, the loss of character isn’t picked up by the Michael of later years. Their journey on screen began ten years before the main high-school era, which shows their mother as a strong-willed immigrant intent on securing a place for her two sons in the intimidating atmosphere imposed by “if it bleeds it leads” news stories. But ten years later, she begins deteriorating mentally. Then some years after that, she’s a shell that Michael is unable to protect, especially without Francis.

Though at many times the film is heart-breaking, and the characters are beaten down, there remains a ray of hope that increases just like the level at which Francis and Michael climb the electrical tower. Though their ascent and eventual triumph goes a long way in creating a timeless, undying relationship, there remains a melancholic aspect to life that is hard to separate from all the best moments. It’s best that we remember the good with (not and) the bad.

Brother will most likely (hopefully) be released in the Fall.

Salty Water (2023, Henrika Kull, Germany) is writer-editor-director Henrika Kull’s third feature film. Swapping out her two previous Berlin filming locations for the mountains between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, the story is constantly shifting between linguistic, geographical, and sexual binaries. Anne (Liliane Amuat) and Nuri (Dor Aloni), who barely know each other, vacation at Nuri’s parents’ house in Israel, which has the persistent presence of military sounds in the distance. They spend the next two days sun-bathing, swimming, and getting to know each other. In a kind of lockdown-era Before Sunset vibe, the pair—though we watch mostly through Anne’s perspective—slowly become attracted to one another as they talk about Germany (Nuri is an Israeli Germanophile) and nationalities in general, a bit of politics, acting and media theory, relationships, etc. (I would’ve liked extended conversations about the politics of their situation—a German woman and Jewish man in present-day Israel…but that wouldn’t have worked with the film’s chill summer vibes.)

The day-to-day, sometimes minute-to-minute, conversations are light-hearted and innocent, which is in direct contrast to both their increasingly buzzing physical connection and increasingly intrusive military rumble in the distance. Although those distant (metaphorical) sounds remains at bay, in contrast to something like Afire, which engulfs everyone in the end, it nicely reminds everyone about the “things left unsaid” in gentle nudges. Aloni’s Munich Filmfest award-winning performance as Nuri is captivating and draws us in, just as it does with Anne. And Amuat as Anne delivers a stunning amount of tension almost purely through looks and body language, which culminates in a brilliant second-act turn when Nuri’s female friend visits and completely changes the sexual dynamic. In one of the moments thereafter, during the second night, the two actors deliver a bone-rattling physical dance with their arms (one of the best two-arm acting performances I’ve seen).

In one of the harder film sub-genres (two-person romantic talkies) to pull off because of its simplicity and over-abundance, Kull found the necessary relationship between the cinematic aspects and interpersonal conflicts.

Salty Water will (maybe) be released in the Fall or Winter.

Save for (a bit) Later

When You Finish Saving the World (2022, Jesse Eisenberg, USA) is Jesse “Mark Zuckerberg” Eisenberg’s debut feature, starring acting friends Julianne Moore and Finn “one of the Stranger Things kids” Wolfhard. In short, Eisenberg made the kind of small family comedy reminiscent in tone and vibe to Noah Baumbach’s The Squid and the Whale, an early acting breakthrough for Eisenberg; Wolfhard plays a similar type of neurotically head-strong teen perfectly suited for a young Eisenberg. The flow of the screenplay also shows his early acting influences, which, again, resembles something Baumbach and Wes Anderson would’ve written in the early aughts: clever language play, fun little observation humor, and double incongruous plotlines that spin out of control in the end.

The story is about how mother (Moore) and son (Wolfhard) veer away from one another as time goes by. Moore is working as a social housing worker for wives/mothers escaping abusive households while Wolfhard is a small-time online music influencer with a predominantly foreign viewership. One day, a mother and son move into Moore’s shelter, and she finds the son to be a perfect representation of how a son should behave: putting his mother’s needs above his, willing to help around with fixing broken things, and other areas where Moore’s lacking the same responsiveness from her own son. Meanwhile, Wolfhard is infatuated with a Leftist classmate, so he then tries to win her over through joining the radical political group and turning her protest poem into a song.

The strength of the story comes from the lengths mother and son will go to pursue the things they think they need the most, oftentimes to cringe-inducing (in a fun way) levels. But in fact, they simply needed each other, with all their imperfections and quirks, all along, which was an obvious ending but nonetheless worked for the lowkey production. Eisenberg’s follow-up will be the test to see if the acting wunderkind can smoothly transition into directorship.

Dalíland (2022, Mary Harron, USA/France/UK) is a hat-trick of film veterans: Mary “American Pyscho” Harron, Ben “Oscar winner” Kingsley, and Barbara “Fassbinder regular” Sukowa. The story is about the 1973 trip of the Dalís, Salvador (Kingsley) and Gala (Sukowa), to New York, told through the perspective of pretty boy Christopher Briney, who just landed a job working at a gallery that is managing the Dalís exhibits. He quickly gets sucked into the Dalíland lifestyle of extravagant parties with Dalí in control of everything, except the Jesus Christ Superstar lead that his wife is sleeping with. The story mainly deals with the relationship between Salvador and Gala, which is an exercise in acting par excellence.

The Edge of the Blade (2023, Vincent Perez, France) is actor-cum-director Vincent Perez’s baguette-and-sword period-piece about Clément Lacaze (Roschdy Zem), one of France’s finest swordsmen in 1887, and Marie-Rose Astié (Doria Tillier), feminist journalist, who takes on the bigoted establishment through dueling. When one man kills Clément’s nephew in a sanctioned duel, Clément duels him in return, which leads to a surface wound, then another man challenges Clément, who offers Marie-Rose in his stead (because Clément’s skills are so far superior, and this is, after all, an honorable affair), who wins the duel before the police break it up, and finally ends with the final boss duel between Clément and the og guy who killed his nephew. While duels are and will always be cinematically awesome, putting four of them, in full, in a feature film is excessive and makes it seem like there’s nothing else in the story.

The main plotlines with Clément and Marie-Rose, which is heavier with the former but should be reversed (in terms of story weight and emphasis), collide towards the second act, but mostly with a whimper that unfortunately casts the two in a needlessly clichéd romance. The dialogue scenes in general, especially with the always anguished and brooding Clément, slow to a crawl between the four duels, which, again, could’ve been livened up with more scenes with Marie-Rose and her band of progressive bohemians.

Dead Girls Dancing (2023, Anna Roller, Germany/France) is another entry into the non-Italians-going-on-vacation-in-Italy-and-then-something-revelatory-happens film genre. In this case, it’s a trio of German girls celebrating their final exams. They drive south and immediately experience problems in the Italian mountains, first with failing to find sleeping accommodation, then with a flat tire, and then with a mysteriously abandoned town, which they think will solve the first two problems. Along the way they pick up Zoe, an Italian girl who doesn’t tell them much about herself—a good sign—and they quickly make the town their own personal palazzo.

Most of the film takes places on a sensual/experiential level, where dialogue slinks along lazily like an Italian pranzo. The locations themselves serve as easy templates for the cinematography to capture, which hovers around and becomes the surrogate Geist haunting the girls. The film played its Metaphor hand a little too thick with the costumed figures. There’s a suspenseful scene involving furniture thieves that plays out excellently cinematically but is immediately undercut in the following scene with a contrived gun plot that seemed entirely unnecessary in the Chekhovian way. The four main actors are good, sometimes great, but the writing doesn’t establish the necessary relationships to make the ending matter, when we finally figure out what’s up with the Italian girl. The final scene was quite nice and a fun Rossellini-type throwback.

Pass

The Kombinant (2023, Moritz Springer, Germany) is a multi-year documentary feature about a cooperative farming group outside of Munich. It shows their struggles from renters to buyers, working long hours on their plot of land, to expanding and finding out how exactly to structure the leadership of a workers’ collective. While the tension of these moments over the years are somewhat intriguing, the production itself was lazy and sub-standard. You wouldn’t have noticed if this were done by the local high-school film club if the filming hadn’t taken place over half a decade. It was also unclear what the filmmaker’s motives were, who seemed more friendly and biased towards the subjects than one ought to get for such a seemingly ideological product.

Boyz (2023, Sylvain Cruiziat, Germany) is an amateur film product that isn’t bad, but still has both legs firmly settled in the non-professional, student-film world. Cruiziat follows around his brother (Maxime) and expat British friends to document their daily lives and social gatherings, who are alarmingly chaste, as nineteen year-olds in university. Most of the energy comes from Maxime leaving for Asia. But that’s not enough to save the seventy-minute film from answering the question, “why are we watching this?”

A Respectable Woman (2023, Bernard Émond, Canada) is a boring French-language drama.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t already done so.