Picnic at the Berlin Philharmonic, Weekly Reel #38

Todd Field shows who the real maestro is, a Franco-Czechoslovak animated classic, more Peter Weir, and a Spanish-Mexican surrealist Marxist film on prostitution

News of the Week: I’m not so interested in horror, so you won’t be getting any of those recommendations.

Watch Now

Tár (2022, Todd Field, USA/Germany) is the first Todd Field, the actor who played the jazz pianist in Eyes Wide Shut, film in sixteen years, which shows in the film’s exploding message of unsilence. He couldn’t hold the sneeze any longer. It stars Cate Blanchett as Lydia Tár (who learned piano and orchestral conduction for this film), a NY-born conductor now leading the Berlin Philharmonic, considered one of the best. It begins with a long interview with the New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik, where they talk about women as conductors (Tár sees progress rather than repression), conductors like Mahler and Bernstein (the latter being a mentor), and her upcoming live recording performance of Mahler’s 5th Symphony. From here we get the scaly sheen toughness of what Tár’s made of, which is a maestro leading at her own time.

She lives in a German Expressionist Berlin flat with Sharon (Nina Hoss), her wife and concertmaster, and their adopted Syrian daughter. Tár’s daily affairs are kept in check by her assistant, Francesca (Noémie Merlant of Portrait of a Lady on Fire fame), who is next up to replace Tár’s assistant composer at the Berlin Philharmonic. Bad news arrives that a former conductor, Krista Taylor, who most definitely had a sexual fling with Tár, killed herself after suffering from depression after being blacklisted by the industry. We then watch Tár scramble to erase all her emails to other organizations that Taylor is a sick person and shouldn’t be hired.

That incident, as well as a spliced video of an interaction at Julliard where she ridicules a BIPOC student for not wanting to play white composers, leads to a downward spiral of a public figure that’s familiar to everyone who’s paid attention to the (American) zeitgeist in recent years. The film is, but not entirely or strictly, about “cancel culture.” Accusations are made, reputations are hit, some shit sticks.

The strength of the film doesn’t come in exposing the indiscretions becoming known, but rather what it looks like from the ground-up on the accused side. Blanchett plays the role so well that one almost forgets about the accusations and just wants to watch her conduct Mahler’s 5th with an accompanying piece by a young Russian cellist, Olga Metkina, who is receiving early Tár grooming. That unfairly then puts into question the rise of her assistant, Taylor’s sudden expulsion, and the relationship with her first-chair wife. That’s the messiness: the accused isn’t the only one fingered. Shit splatters to those closest to you, no matter what merit you wield.

Todd Field’s epic isn’t interested in righting wrongs or settling scores or getting even. He wanted to make a film about the current era that took the vibes and left the baggage. It’s the film of our time more than anything else in a long time by taking the universal and making it discrete. It’ll give Cate Blanchett the Oscar nod and probable win—she snagged Best Actress at Venice for Tár. Hildur Guðnadóttir, the film’s composer and winner of the original score Oscar for Joker, crafted an atmospheric soundtrack that was equal parts Mahler, Guðnadóttir, and silence. Throw in directing and writing noms for Field, cinematography nom for Florian Hoffmeister, supporting actress noms for either (or both) Noémie Merlant and Nina Hoss, and you can see the outlines of the 95th Academy Awards.

I highly recommend watching the film while it’s still in theaters. How else will Mahler’s Symphony No. 5, I. Trauermarsch movement blast your skull?

Save for Later

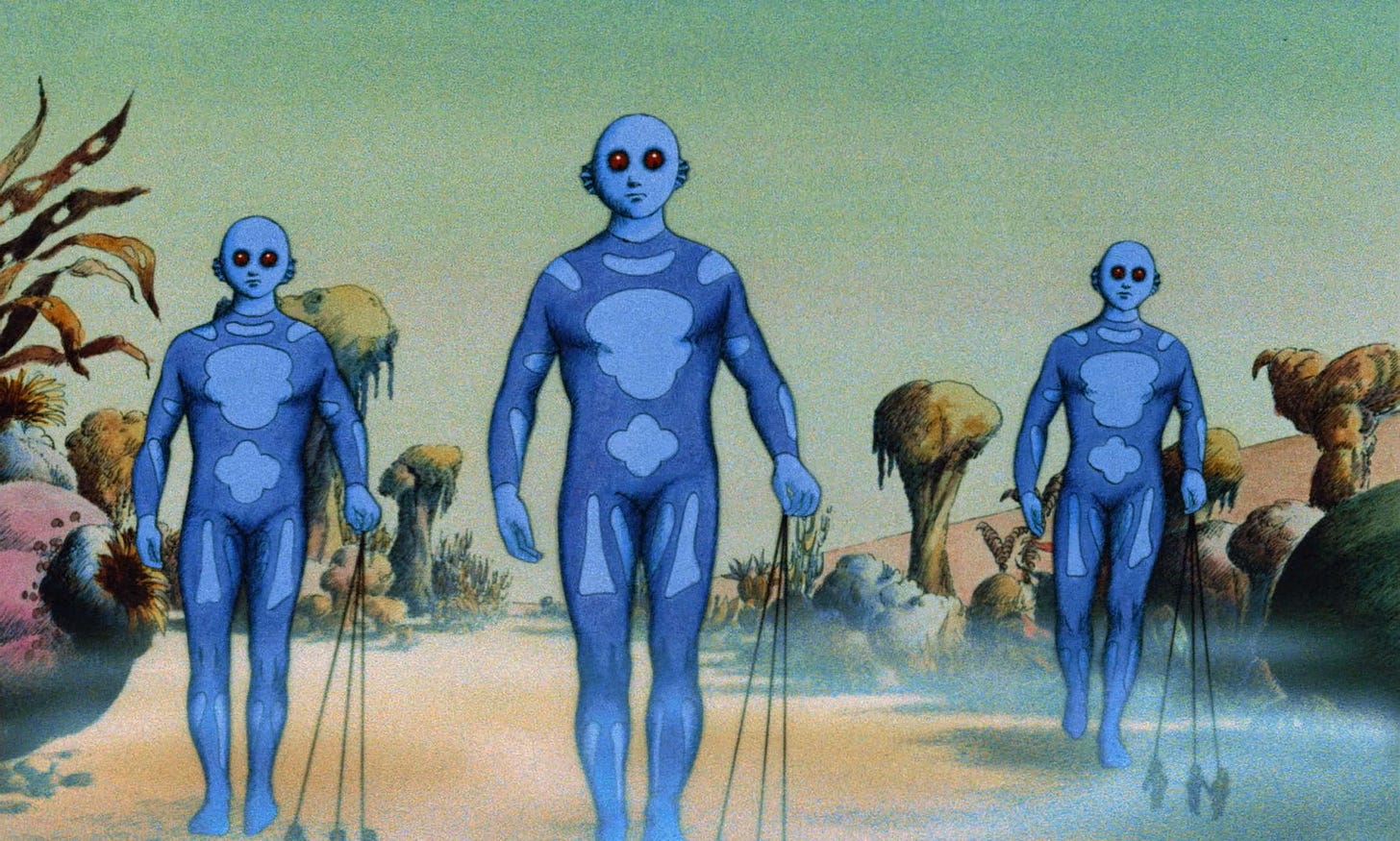

Fantastic Planet (1973, René Laloux, France/Czechoslovakia) is a French-led animated film crated in Prague (while it still stood behind the iron curtain). Based on a French science-fiction novel (Oms en série by Stefan Wul), it’s about a planet where humans, called Oms, are the size of ants in the shadow of giant humanoids called Traags. The Traags play with the Oms like they’re pets, which every few generations have a small uprising that leads to a de-oms program of species purgatio. We follow what happens when a house-trained Om, Terr, is orphaned and raised by a young Traag. He learns their language, history, culture, and dress. One day, Terr escapes after his Traag grows old of him, who steals her knowledge tiara that transmits knowledge directly into one’s mind. On the run, Terr runs into a wild tribe of Oms that are planning an uprising against the Traags.

Even though this film is animated and science-fiction, it’s French, therefore, it has nudity. Also French is the film’s ability to make a more adult version of a naïve American classic, the Disney animated film. Disney films, always being the most toned-down version of allegories designed to scare children rather than get them to buy stuffed animals and amusement park tickets, never go so far in their fables and parables. Fantastic Planet’s allegory is harder to place because it describes the story of an entire generation of ethnic and national rage finding a voice in the sixties and early seventies. For the Franco-Czechoslovak filmmakers, the Algerian War, the Prague Spring, and the apparatus of their ideological separation by a concrete wall in Berlin. And Hitler’s invasion of both countries was only a generation before that…

But the film isn’t a 1:1 allegory/fable like Animal Farm. It tells its own self-contained story within a strange and fantastic planet that flips the table of humanity’s godliness. You should check it out yourself and see the fine and now extinct craftsmanship of artists painting images onto frames; it’s available to subscribers of HBO Max and streaming free, with ads, on Plex and the Roku Channel.

Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975, Peter Weir, Australia) is a mystery based on a 1967 novel of the same name by Joan Lindsay. It takes place on St. Valentine’s Day in 1900 at a private girls’ school in Victoria, Australia. The girls are allowed to visit the base of hanging rock, a mamelon reaching 718 meters above sea level. Four of the girls ask for permission to roam around the rocks and they slowly make their way up the formation. Nearing the top, the four girls are whisped by supernatural forces into a short sleep. When they wake up, three of the girls take off their shoes and stockings and disappear behind one of the rocks. The fourth girl fails to understand what they’re doing and eventually runs down the mountain screaming in horror. Unseen to us, the teacher chaperoning the girls also climbs the formation and passes the screaming girl, who noted that her teacher didn’t have pants on. Two young men watched the four girls when they began their ascent, who later become interested in their re-appearance when the town starts a womanhunt for the three girls and their teacher.

If you recall from last week’s review of Master and Commander, I’ve been going through Peter Weir’s films, this time watching one of his earlier classics. This was during the Australian New Wave (early seventies to late eighties, which spawned the careers of Nicole Kidman, Sam Neill, George Miller, and Mel Gibson) that picked up where New Hollywood left off, but with an Aussie twist. For Picnic at Hanging Rock, this meant a reverence for and repulsion of the outback—they weren’t technically in “the outback” for this film, but I won’t tell if you won’t. The Hanging Rocks have a mysterious pull to them, which relates to the magnetic pull of lust. It’s St. Valentine’s Day, the girls are constantly reciting love poetry, and there are multiple forms of (both male and female) homosexual relationships bubbling underneath. All the girls and teachers are specifically drawn to Miranda, who the French teacher refers to as a Botticellian Angel after just looking at “The Birth of Venus.”

The mystery works well for an American audience because they’re addicted to young (and blonde) missing girls’ stories. Even though the film is based on a book, it was reported that American audiences, after the film ended, were obsessed with the details of the case and in particular the haunted ending. It isn’t a typical procedural, so don’t expect the same “case closed, done deal” plotline. It’s ethereal, haunting, tender, never un-intriguing, and viewable on HBO Max.

Belle de Jour (1967, Luis Buñuel, France/Italy) is one of the great films of one of the greatest filmmakers of all time. It stars Catherine Deneuve, a young housewife that decides to be a prostitute during the day (the name “belle de jour” comes from a play-on words for prostitute, “belle de nuit,” meaning beauty of the night) between the time she finishes chores and when her doctor husband comes home. She takes this path after having intimacy problems with her husband, whom she loves a lot, but who can’t fulfill her sadomasochist, bdsm fantasies—c’est dommage. She spends the film dealing with this tension, especially after one of her dangereux clients becomes obsessed with her.

Deneuve plays the classic “hooker with a heart of gold” character, but never makes it a caricature nor does Buñuel drop into exploitative sludge. It resembles Catholic guilt more than sexual ethics (if we’re going with the morals is sex and money is ethics prostitution binary). Buñuel was highly religious in his youth and had a great many films dealing with similar tensions when they weren’t harpooning class hypocrisy. Deneuve undoubtably loves her husband but needs to get off. These are dilemmas that modern society, at least in 1967, had failed to settle. ENM wasn’t in the lexicon. Deneuve punishes herself for these thoughts and intimacies but doesn’t let it stop her from working at Madame Séverine’s maison.

Anyone interested in this amazingly sensitive film can watch it on HBO Max.

Pass

Again nothing.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t already done so.