Zora Neale Hurston, Cudjo Lewis, and Franz Boas

How Zora Neale Hurston developed her unique writing style through interviewing Cudjo Lewis, survivor of the last slave ship, and black communities in the South

With the recent release of The Woman King, I decided to revive my essay on Zora Neale Hurston’s experience with interviewing Cudjo Lewis, who was on the final slave ship that landed in the USA in 1860. The Woman King is about an all-female military unit of the Dahomey Kingdom in the eighteen-twenties that realize their participation in the salve trade is evil and should replace it with palm oil.

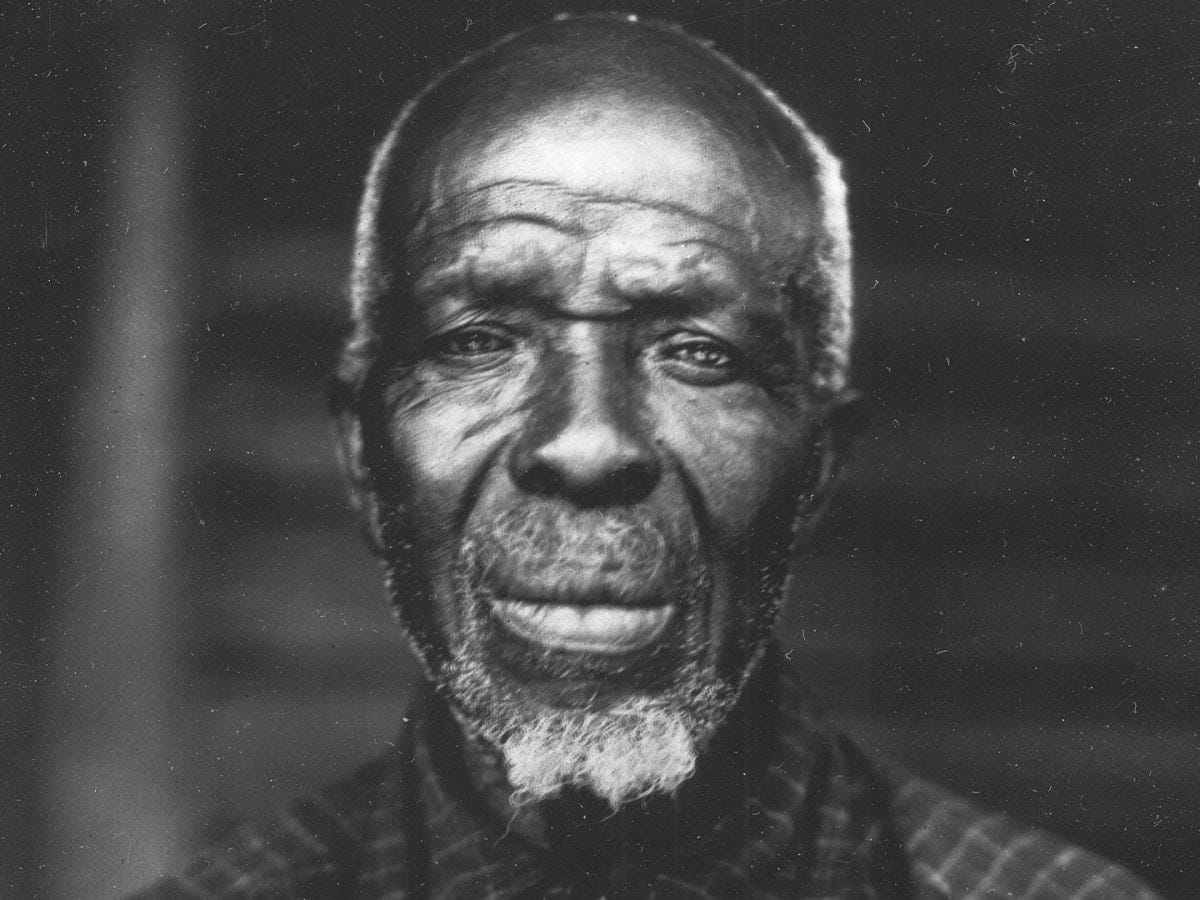

Contrary to the forgivable historical sleight-of-hand the film employs, Cudjo Lewis recounts his story, in two interviews with Hurston in 1927, about an all-female unit of the Dahomey Kingdom that slaughtered his entire village and sold its stronger members into slavery. This happened three decades after the events portrayed in The Woman King.

But far from being a complete form of revisionism, The Woman King directly confronts the issue of West African involvement in the slave trade, which black writers and artists in the USA during the Harlem Renaissance deliberately suppressed. The best example of this is Barracoon, the book Hurston wrote based on her interviews with Lewis, which publishers refused to publish because of its violent recounting of a West African kingdom enslaving other West Africans.

Barracoon was finally published in 2018, which importantly solidified both Hurston and Lewis’s contribution to American and West African history. Below is an essay I wrote after Barracoon’s publication, which tells the story of how Zora Neale Hurston, who was always sidelined during her career as a black female writer, had developed her unique writing style from her times as an anthropologist interviewing black communities in the South.

Zora Neale Hurston and Franz Boas

Zora Neale Hurston’s life before entering university in 1918 at the age of twenty-seven is story unto itself. Born in Alabama, her family moved to Eatonville, Florida—one of the first all-black incorporated towns and setting of her magnus opus, Their Eyes Were Watching God, a text so canonical that it inspired part of Beyoncé’s Lemonade—in 1894. A few years later, her father became mayor. The town offered the unique advantage as an escape from white society in the Jim Crow South. Her literary education began after northern schoolteachers visited their town and handed out books. But then she moved to Jacksonville.

In her 1928 essay, “How it Feels to be Colored Me,” she explains how this transition felt: “I was not Zora of [Eatonville] any more, I was now a little colored girl. I found it out in certain ways. In my heart as well as in the mirror, I became a fast brown—warranted not to rub nor run.” This disturbance of moving from an all-black town to a multi-ethnic city had a profound effect on her conception of race and culture, the effect of which may be why she wanted to study anthropology and African folklore, which could also enhance her growing interest in literature.

This experience and others like it showed her that racial judgments are emotionally irrational, that culture is something geographically relative because she only experienced herself as “colored” when moving to a racially mixed city. In Eatonville she could freely express herself as an individual but not in Jacksonville. Hurston thus turned to the solitary act of writing not only to accurately represent the real ‘Zora’ rather than the ‘colored girl,’ but also to understand the fundamental differences between the two.

By the time she was old enough to attend high school and college, her education consisted of ethnic cultures (as anthropology) first, literature second, and manual labor third. She was savvy enough to finesse a free high school education at Morgan State University, an all-black Maryland college. Then she attended Howard College, another historically black university, where she earned her associate degree. At Howard she began writing stories, which ingratiated herself with Alain Locke, the “Dean” or “Father” of the Harlem Renaissance. Then, which would be her most crucial move, she received a scholarship to Barnard College of Columbia University, a women’s college where she was the only black student.

Alain Locke urged Hurston to study anthropology while she was attending Howard university. Attracted to the nineteen-twenties literary scene taking place in Harlem, Hurston attended Barnard College because it was connected to the anthropology department at Columbia University led by Franz Boas, the German-born innovator, some say “Father,” of cultural anthropology. By 1925, Boas had been teaching his own culture-based anthropology and instructing his students in ethnographic collection, which, among other things, stressed the study of cultures detached from race to better understand groups of people. By conceptualizing cultural groups as distinct entities divorced from race, scientists were able to examine each according to their own rules without comparing their disparities. Boas incorporated this idea of cultural relativism, though not new, into the field of anthropology while scientific racism was a standard academic and popular consensus on explaining group difference. He first developed the concept while living amongst the Baffin Island Eskimos in the 1880s; his conclusion from the trip was that “the Eskimo is a man as we are. His feelings, his virtues and his shortcomings are based in human nature, like ours.” Turning this thesis into a scientific discipline, his intention in starting and spreading cultural anthropology “was to deny hierarchy, and to minimize the difference between the binaries of barbarism and civilization.”

Boas found race to be an imperfect cultural descriptor and “scientific dead-end.” As racial superiority theory manifests in one’s attitude towards ‘inferior’ cultures, it isn’t “based on scientific insight but on simple emotional reactions and social conditions. Our aversions and judgements are not, by any means, primarily rational in character.” Although this seems obvious today, Boas was organizing and disseminating a heterodox position in the social sciences that was directly attacking the scientific racism at the core of eugenic policymaking in the Jim Crow South. Boas, for instance, argued that because Africans had a developed culture in Africa but not in the Americas, white people “in the United States were responsible for holding back black achievement.” Hurston was attracted to Boas because of his racial and cultural openness towards Africans and African Americans that was absent during her schooling.

Hurston would later write that Papa Franz was “the king of kings” because of his dedication to work and getting the best out of his students and colleagues. The reason he was the “greatest anthropologist alive” was because of “his insatiable hunger for knowledge” and “genius for pure objectivity,” even correcting his own theories if he found evidence against them. Once under the participant-observation fieldwork training of Boas (the method he developed on Baffin Island), Hurston received the tools and guidance needed to examine her past, specifically that which relates to the folk history and stories of Eatonville. Anthropology was unique in being able to scientifically conceptualize her experiences because it created models of subjects that white racism consistently distorted into stereotypes. In other words, cultural anthropology allowed her to dignify black folklore and re-evaluate black expression for the better.

For Hurston’s first collection of folktales, Mules and Men, she returned to the South to collect black folklore, this time as an anthropologist. Involvement was easier for Hurston than other fieldworkers, who were usually white males, especially when studying Eatonville. It also gave her the opportunity to confront racist stereotypes about rural, southern black life, which was the dominant theme of minstrel shows, the biggest form of entertainment at that time. At the core of Hurston’s career was this question of authentic representation of identity, which is why she moved to nineteen-twenties New York to take part in the Alain Locke-led “New Negro” movement of the Harlem Renaissance. Although Hurston had a boisterous personality, which stood out from the rest of her friends, especially Locke and Langston Hughes, she approached the literary scene from a uniquely scientific perspective. Hurston was therefore an anthropological outcast in the Harlem Renaissance and a literary outcast in Barnard’s rigorously scientific approach.

While involvement was easier for Hurston because of her Eatonville background and likeable personality, the detachment was difficult for her to reconcile because of the conflict between representing subjects in a scientific versus literary manner. Unlike most students of Boas, Hurston was primarily an artist with literary sensibilities, which had its limits when applying scientific conventions to objectively representing a subject. The tension was between the subjective folk experience and the abstract knowledge of that experience. Hurston’s aesthetic sensibility was at odds with the standardization created by the scientific method of analysis and representation; Hemenway called this Hurston’s “vocational ambivalence.” By taking a scientific approach, she risked destabilizing her implicit connection to the culture, but choosing a literary approach risked decoupling community from culture as the individual is privileged.

Mules and Men was popular with the public but not with scholars because of its style and questionable authenticity—Hurston had lied to the community to gain admittance and fictionalized some stories to better fit literary conventions. But Boas commended the text in the foreword. This, along with other author’s articulations, showed that while academia in general had standards of objectivity and representation for their monographs that Hurston was breaking, Boas and his closest colleagues, as the radicals they were, sought to shape the field of anthropology to something more resembling Mules in its approach to representing the inner truth and life of their subjects. Therefore, Hurston’s writing became the radical embodiment of Boasian cultural anthropology.

The writing style that resulted from this period of scientific training in Hurston’s life was a blend between literary conventions and anthropology. This kind of “post-modern ethnography” became popular half a century later, which Hurston had originally used as a bridge between readers as far apart as her mentor and his colleagues, and the general reading public. Ruth Benedict, another student of Boas and highly influential anthropologist, offered a similar approach from her poetry background. One of her most profound theses was that to better understand cultures, anthropologists need to include humanistic studies regarding the minds of men; to better understand the inner truth of man, one should combine scientific analysis with a humanistic, social science analysis. Susan Hegeman calls this sub-genre that Boas and his pupils developed the “aesthetics of cultural relativism.” Their objective was “to deploy intercultural comparisons to critique modern society and free the individual from the social constraints imposed on them through the combined effects of ignorance, fear, and maintenance of social power.”

Cudjo Lewis and Barracoon

It’s my thesis that Hurston arrived at this ‘aesthetic of cultural relativism’ precisely between the two times she interviewed Cudjo Lewis. Tasked with interviewing him in July 1927 for Carter G. Woodson’s Journal of Negro History under the guidance of Boas, Hurston drafted an article titled, “Cudjo's Own Story of the Last African Slaver.” One linguist argued that Hurston plagiarized seventy-five percent of it from Emma Langdon’s Historic Sketches of the South. The text is in a third-person, non-participation observatory style with no author-intrusions like in Mules and Men; most of the descriptions are matter of fact and, most importantly, the dialogue was sanitized of any vernacular authenticity.

This first interview took place during Hurston’s first fieldwork mission. Hurston went back to Boas and “cried salty tears” because of the embarrassing failure of not collecting original folklore material during the trip. It’s here, with Boas’s advice upon returning, where Hurston had an “epiphany.” She wrote to Langston Hughes on her second fieldwork trip that she was finally “getting inside of Negro art and lore [and] beginning to see really.” Hurston found that she couldn’t properly transcribe this art and lore with existing methods; therefore, she needed new literary strategies to appropriate this vision. Hurston’s epiphany came from finding the problem of representing the folk-subject and their inner realities through using the written word. The rigid scientific method of collecting and presenting data was inauthentic to her, which may be why she plagiarized.

In giving Hurston advice to collect original material on her next trip, Boas stressed manner and style rather than matter and substance; to pay attention to “the form of diction, movements, and so on.” Any white fieldworker could observe and report, but Hurston had a unique insider position that could find the un-sanitized folk style. Boas wanted the collecting to focus primarily on manner, style, diction, and movements because that is what reveals the inner truths and identity of a cultural group. With this new piece of insight and bitter experience from her first trip, Hurston traveled back to Florida to interview Lewis again to right her previous errors, which resulted in a wealth of material used to write the manuscripts for Barracoon and Mules and Men.

Although unpublished until 2018, Barracoon presents the earliest story of Hurston’s writing as developed from Boasian anthropology. In the preface, Hurston writes, “this is the life story of Cudjo Lewis, as told by himself. It makes no attempt to be a scientific document, but on the whole he is rather accurate.” Contrary to Hurston’s first essay on Lewis, this book follows Hurston’s attempts to contact Lewis at his home in a first-person, direct-participation narrative style. Hurston tells the story of Lewis’s life using his own words, dialectically verbatim, from beginning to end. The narrator’s only function is to describe the manner, style, diction, and movements of Lewis. For example, in the first chapter Hurston wants to hear about Lewis’s life rather than his family, but Lewis

gave [her] a look full of scornful pity and asked, “Where is de house where de mouse is de leader? In de Affica soil I cain tellee you ‘bout de son before I tellee you ‘bout de father; and derefore, you unnerstand me, I cain talk about de man who is father (et te) till I tellee you bout de man who he father to him, (et, te, te, grandfather) now, dass right ain’ it?” (20-1)

And rather than countering or judging Lewis directly in their discussion or through narration, Hurston allows Lewis to tell his whole story. And by letting Lewis speak for himself, Hurston converted Lewis into a subjective character rather than an objective informant. Hurston’s solved her original problem of authentic representation of objectivity through subjective self-representation.

This authentic representation confirms Boas’s impact on Hurston’s writing, especially his main thesis of cultural relativism. Hurston and other Boasians developed a form of aesthetics that stressed the representation of a foreign culture absent of either positive or negative judgment. For example, in Barracoon, Lewis narrated the day a neighboring West African kingdom, the Dahomey, attacked his village and killed or enslaved everybody. In the book’s foreword by Alice Walker, who raised Hurston’s writing out of obscurity in the nineteen-seventies, she claimed that these African inflicted atrocities on fellow Africans was a “problem that many black people, years ago, especially black intellectuals and political leaders, had with” the content of Barracoon; “we are being shown the wound.” After Lewis finished telling the story of his village’s destruction, Hurston, without speaking, watched while “his face was twitching in abysmal pain” as he stopped talking. This is a particularly powerful passage; rather than hold malice against those who enslaved him, whether West African or European or American, Lewis internalized the suffering and still sees the ‘wonders of life.’

The main tenet of cultural relativism is in the limitation of claiming superiority when comparing one culture to another. In Barracoon, Hurston doesn’t claim that Lewis’s rural life is a more authentic or worse form of living. To do that, one must overcome one’s own cultural biases. Authentic representation is not only a process of letting the subject speak for themselves, but also for the author/collector to successfully adapt themselves to a foreign culture. Although this is the main theme of Mules and Men, Barracoon conversely presents a successful role of the involvement step of the participant-observation method that others claimed was impossible. For instance, Hurston skips town at the end of Mules and Men because of her failure to embed herself within the community, while in at the end of Barracoon, Hurston recalls that they became “warm friends” and had a sad goodbye.

Hurston was able to arrive at a successful conclusion with Lewis precisely because of her understanding that, as Benedict would argue later, the humanities’ quest for understanding the minds of men needed to be present when analyzing a subject. To gain Lewis’s trust, Hurston would bring him food, help him work, and respect his work schedule. Furthermore, a narrative trajectory takes place that confirms Hurston’s epiphany. In the first several pages, Hurston was anxious to get answers, which hindered Lewis’s own process of telling his life story. For instance, only minutes after approaching Lewis, Hurston asks, “but didn’t you have a God back in Africa?” Lewis, without answering, cries because he hasn’t seen Africa since he left, then responds, “how come you astee me ain’ we had no God back dere in Afficky?” (18-19). Hurston then adapted herself to Lewis, noticing that he’s happy to tell his story without her interruptions—and when food was available. By the end, Hurston’s only comment on the collection process was in writing, “I had spent two months with [Lewis]…trying to find the answers to my questions.”

Thus, with Barracoon, Hurston not only reconciled her previous failure in writing about Lewis, but in the process discovered and perfected a writing style that is evident in her best works: vernacular speech, individual authenticity, cultural relativity, etc. The importance of Barracoon is both in its portrayal of Lewis as a subject rather than scientific object, and how Hurston adapted herself to properly capture him as a subject. This process was a direct embodiment of the participant-observation method that Boas taught. In this way, one can present the inner truth of a subject, which was important for the stipulation that all cultures, being relative, have their own realities detached from broader descriptor categories like race. Hurston’s specific interest in this process was in allowing her to present a culture as it is without judging it against another culture or used as a racist stereotype. And by doing so, she solved her own problem in “how it feels to be colored me,” which is the title of an essay she wrote a year after coming back from interviewing Lewis. I’ll conclude with the final paragraph of the short essay, which I highly encourage all of you to read:

But in the main, I feel like a brown bag of miscellany propped against a wall. Against a wall in company with other bags, white, red and yellow. Pour out the contents, and there is discovered a jumble of small, things priceless and worthless. A first-water diamond, an empty spool, bits of broken glass, lengths of string, a key to a door long since crumbled away, a rusty knife-blade, old shoes saved for a road that never was and never will be, a nail bent under the weight of things too heavy for any nail, a dried flower or two still a little fragrant. In your hand is the brown bag. On the ground before you is the jumble it held--so much like the jumble in the bags, could they be emptied, that all might be dumped in a single heap and the bags refilled without altering the content of any greatly. A bit of colored glass more or less would not matter. Perhaps that is how the Great Stuffer of Bags filled them in the first place--who knows?

Miraculously, Hurston’s footage of Lewis and her Southern travels survived. She even narrated and sang through it:

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t already done so.