State of the Film Union 2023

Every year, as usual, is an important year for film. The stakes were raised more recently because of #metoo, streaming services, and pandemic shut-downs. We’re now seeing the returns.

In this overview, I discuss the macro-issues of the film industry over the last year. It’s neither an exhaustive analysis nor one judging the good and bad. I divided it into two sections: Theaters and Streamers; and Films. If you want longer reviews of the films I mention, you can find all of them in Weekly Reels.

Theaters and Streamers

The two biggest developments is the increased number of theatrical visits, relative to last year, and stagnation of streaming services. In 2020, the number of tickets sold domestically (USA and Canada) dropped to 223 million, a 1 billion ticket decrease from 2019. In 2021 it grew to almost half a billion and in 2022 it reached 813 million. While theaters aren’t fully “back,” they’re showing an increase that disproves many people who claimed covid killed theaters. (The bankruptcy of Regal theaters and clown CEO of AMC, as well as studios failing to provide enough content to program, are doing a better job than covid.)

The long bet on theatrical attendance is a slowly descending line from its peak in the nineteen-fifties. Raising ticket prices and using variable price gimmicks like 3-D and Imax are delaying the inevitable. But that only accounts for the big budget tentpoles. Cinephiles who want to watch foreign and independent films will always be able to enjoy them at smaller cinemas, which are small enough to get by on celluloid sniffers alone (but only in bigger cities).

Studios have foregone the mid-budget films in favor of the $250 million existing IP, which will hurt them in the long-term when the cash cow dies. While that isn’t new, it’s now beginning to hurt their ability to provide enough content for their streaming services, which requires a massive amount to keep users engaged and subscribed. Services like Paramount+ and Peacock will feel the worst of it as their meager content libraries fail to justify continuously losing quarters without a profitable horizon. Disney, for instance, can afford the massive operating losses because of their parks, merchandise, and ESPN revenue.

Wall Street decided, arbitrarily, that streaming subscription numbers would be the sole measure for a studio’s value. Everyone decided to immediately shift their content online, exclusively to their services, and compete against Netflix. Only Disney and Warner Bros. Discovery have any realistic competitive edge and everyone else will have to merge or sell.

This was made worse last year when, for the first time ever, Netflix reported a quarterly loss in subscription numbers. This sent stocks down across the board and made everyone pause. Was 220-230 million worldwide subscribers the limit? Netflix’s response: time to crack down on password sharing and introduce an ad-tier, which will permanently alter the streaming service landscape from 2023 onwards.

Not only Netflix, but every service added an ad-tier because it became incredibly expensive subscribing to multiple services. (It also helps them advertise a lower price and bundle with other services.) This is why FAST (free ad-supported TV) services like Pluto TV and Tubi became so popular.

The stagnation of full-service subscriptions, introduction of ad-tier subscriptions, and increase of FAST is the system self-correcting and reaching an equilibrium now that all the major players are on the field.

The streaming bull market cooled off half a year later and every company is now reaching austerity. The apps are too expensive to justify the losses now that subscription numbers aren’t rising like they did during covid, which was a rocket ship that burned its fuel supply too quickly.

Unfortunately, we, as users, will bear the cost: rising subscription fees, fewer titles available and for a shorter period, and whatever strange method Netflix will use to stop people from sharing passwords (which will then be copied by everyone else).

Interlude: Studios

The two legacy studios that set the agenda for the rest are Disney and Warner Bros. Discovery (WBD). When Bob Chapek became CEO of Disney in February 2020, he may have received the worst luck of an incoming CEO of all time. Covid destroyed their Parks business, the department he came from, and they couldn’t release films in theaters. That may have increased the subscription numbers of Disney+, but it led to Scarlett Johansson suing the company and a souring between talent and CEO.

Then the “don’t say gay” bill backed Chapek into a corner between appeasing his employees and Florida’s state government. (He pissed both off.) Pixar’s first film since early 2020, Lightyear, was released theatrically to awful reviews and tiny box office. Many, me included, blamed that on consumers used to Pixar titles released through Disney+.

Then in November 2022, Disney released another animated film to bomb at the box office and Disney’s stock price reached early covid levels. Weeks later, Chapek is fired by the board, who then re-hire Bob Iger, Chapek’s predecessor, the beloved CEO whose resignation led to the Chapek years in the first place. Iger had a solid tenure (acquiring Pixar, Marvel, Lucasfilm, and 20th Century Fox), but he still failed to stick the landing. (Iger, rumors are saying, was brought back for another big Disney move. The highs would be an Apple buyout and lows would be a Hulu sell-off.)

In mid-2022, AT&T spun-off WarnerMedia to Discovery, which created WBD. David Zaslav, who was central to the merger, became CEO and immediately implemented changes: like Disney+, they introduced an ad-tier for HBO Max (which will be changing its name very soon to reflect Discovery’s contribution); they vealed the newborn CNN+ and placed Chris Licht as CEO of CNN to reduce the amount of bias political coverage; James Gunn and Peter Safran became co-chairmen and co-CEOs of DC Studios (and scalped the already filmed Batgirl), who are changing up DC to exclude Henry Cavill as Super-Man and re-invigorate an extended universe that Zach Snyder worked very hard to destroy; more generally, Zaslav is turning around the company’s stalled assets and converting it into a Disney/Netflix competitor.

Overall, the moves are a solid decision to avoid complacency, which are the futures studios typically trade in. DC at the very least needed a major change, as well as a CNN re-branding, but the decisions have led to a lot of unfavourability among talent (see: Batgirl controversy). It was 2021 Warner Bros. that decided to release all their films in theaters and through HBO Max the same day, which hurt their box office returns and sent Christopher Nolan, their most reliable loyal moneymaker, to the highest bidder (Universal). We’ll see if the changes are for the better.

Films

To everyone’s surprise, the highest grossing films of the year are sequels of existing IPs. Top Gun: Maverick, a film that I’ve exhausted my energy thinking about already, surprised everybody. The popularity of the film is something, I think, that is quite troubling for a country with an empire in decline, funding a war against a nuclear power, and has states that don’t wish to be part of the same union. (As I’m writing this a man in a Top Gun: Maverick hoodie walked into the café.) The hyperbole reached a crescendo when the “greatest generation” glorifier himself, S. Spielberg, said the film saved Hollywood. From what? The Chinese?

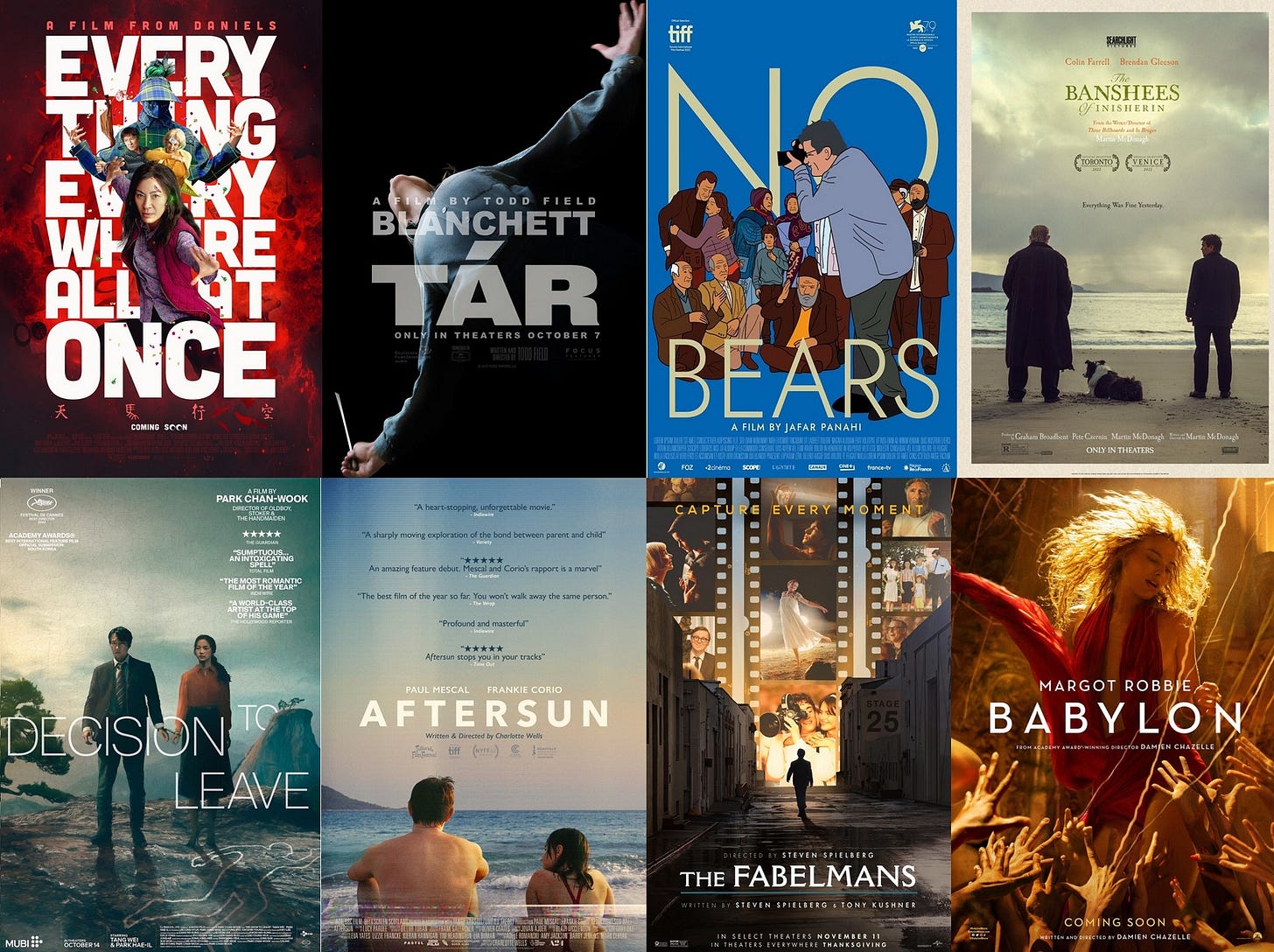

Overall, the themes coming up among the acclaimed and popular films are filmmaking itself, “eat the rich” jests, and memory. All three are direct reactions to the pandemic: people, when they began re-prioritizing and reflecting, found importance in the art of filmmaking, saw the criminality in billionaires becoming 62% wealthier during the pandemic, and had more time to think about the past and how the process of thinking itself works.

In general, the films about, or adjacent to, filmmaking (The Fablemans, Nope, Babylon, Bardo: False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths, No Bears, Empire of Light, Pearl, X, Blonde, etc.) are also about memory. In most of them, they reveal what filmmaking means on the personal level, whether it’s a childhood obsession that solves traumatic family events or a director harshly judging himself for leaving his home country to receive critical praise from another.

The two best films about filmmaking are Jafar Panahi’s No Bears and Jordan Peele’s Nope. (The Fablemans also deserves a shout-out for itself maestro writing and direction and how it reveals the power of filmmaking, as well as the final montage of Babylon, which shows you the visceral power of cinema over time.) No Bears is a lightning in a bottle film that could only be achieved because of the unique circumstances of Panahi’s life and position within the film community while Peele similarly provides a thesis statement on cinematic spectacle.

Panahi, who plays himself as a filmmaker staying at an Iranian village on the Turkish border while his crew is filming in Turkey, is both literally and metaphorically about a filmmaker at the edge of society and possibility for escape on the other side of the hill, where the grass may be greener. He exemplifies the best of Iranian cinema and international cinema in general, all while being confined to limits of the country and with a filmmaking ban.

Nope, at the opposite end of the No Bears spectrum of filmmaking, is a big-budget Hollywood film about the historical experiences of a minority group, about how these people were once the spectacle, many times degraded into animalistic roles, and how they could reclaim agency through filmmaking. In that way, and through Peele’s blank check for an original idea, Nope also exists in a historical vacuum that could only exist under the current conditions for one director.

While “eat the rich” stories have always existed, this year we received a steady dose (of mostly duds): Glass Onion, The Menu, and Triangle of Sadness. Films criticizing the very wealthy are hard to achieve without turning into cringe satire. It comes down mostly to taste; all three of these post-Parasite films rely on humor to support their theses when they should be relying on story/plot.

Triangle of Sadness, which won the Palme d’Or, is a successor to Ruben Östlund’s previous film dealing with similar concerns of elitism but in a different location, like Glass Onion. And both were criticized for failing to imagine new realities. (I agree in the case of Glass Onion, but not Triangle of Sadness.)

There’s a point at which these stories criticizing the rich become the court jesters, where they can remain as the safe opposition wholly controlled by the elite. It’s even worse when the film isn’t good or interested in delivering anything beyond terrible improv takes. Studios wanted to capitalize on Bong Joon-ho’s success and filmmakers were willing, but had no foundation, whether by upbringing or theoretical knowledge, to draw upon.

For most (of the competent) filmmakers, memory was what everyone was memorializing. A short list includes: Empire of Light, Aftersun, The Fabelmans, Irma Vep, Top Gun: Maverick, Elvis, Three Thousand Years of Longing, Armageddon Time, Apollo 10½: A Space Age Childhood, jeen-yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy, Alcarràs, and, dare I say, Jackass Forever.

The two most revelatory are Charlotte Wells’s debut feature Aftersun and old man S. Spielberg’s The Fabelmans. Both offer takes from their youth; Wells returns to a Turkish resort with her father and Spielberg delivers the canonical take on his childhood, from the birth of a filmmaker to what went down with his parent’s divorce.

Confronting one’s past is difficult. On Sophie’s thirty-first birthday, she recalls the time her father turned the same age on their trip to Turkey together. She watches old tapes and remembers through seeing it from her father’s perspective, who had problems she saw at the time but didn’t become tragic until later. Her memory is hazy and filled with a lungful regret, and Wells doesn’t revert to cheap nostalgic tricks to fill in any gaps.

Spielberg took about three times as long to look back at his childhood, which he didn’t want to film until his father passed away (which was in 2020 when he was 103 years old; not bad Arnold!). The Spielberg myth in the seventies and eighties was a father leaving his family. Then later, which was partially revealed in the HBO doc Spielberg, the great twist was a mother splitting up the family to marry the father’s best friend. His father took the blame to protect the mother. Spielberg didn’t talk to his father for fifteen years. The Fabelmans changes some of the geographic details but remains faithful to the most consequential family breakdown in cinematic history, thanks, in part, to co-writer Tony Kushner’s persistence.

Wrapping up the films of the year, it should be noted that films are still becoming longer than usual: Avatar 2 is 190 minutes, Babylon is 188, The Batman is 176, Black Panther 2 is 161, Elvis is 159, Tar is 158, and The Fabelmans is 151. These runtimes turn a lot of people off who aren’t invested in the blue-people world or caped crusader, but this is how studios are justifying why people should make the trip to the local cinema, which isn’t new of course, but how long can we remain in this never-ending ‘death of cinema’ content spiral that more and more resembles the late nineteen fifties each year? While cinema still has to compete with TV, it also has to compete against itself on streaming, which is where most people today are waiting to watch the big-screen flicks.

However they maneuver out of this dilemma may or may not hurt their bottom line, but we, the viewers and lovers and paying regulars of good films, will be the losers.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t already done so.