The right is still obsessed with Henry Wallace for some reason

As the USA ramps up Cold War 2.0 against China, not even Henry Wallace is safe: a post-post-post-revisionist review of "The World That Wasn’t" by CFR spook Benn Steil.

(Note: I shopped this review to a number of publications, to no avail. Nobody wanted a 3.5k-word amateur book review of a now-irrelevant New Deal-era politician, what is this world coming to?)

A little-known event took place a month after D-Day that arguably had the greatest impact on the fate of postwar events.

In Chicago the Democratic National Convention was to decide who would run, President and Vice President, in the 1944 election. Roosevelt easily secured his fourth Presidential nomination while his Vice President, Henry Wallace, lost on the second ballot to Harry Truman. As politics go, there were dirty behind-the-scenes maneuvers on both sides—not dissimilar to Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020, but what made this the most consequential nomination, perhaps of all time in U.S. history, was because political leaders had recognized that Roosevelt wouldn’t survive the term. WW2 was entering its final act, and the world would soon become anew under American domination.

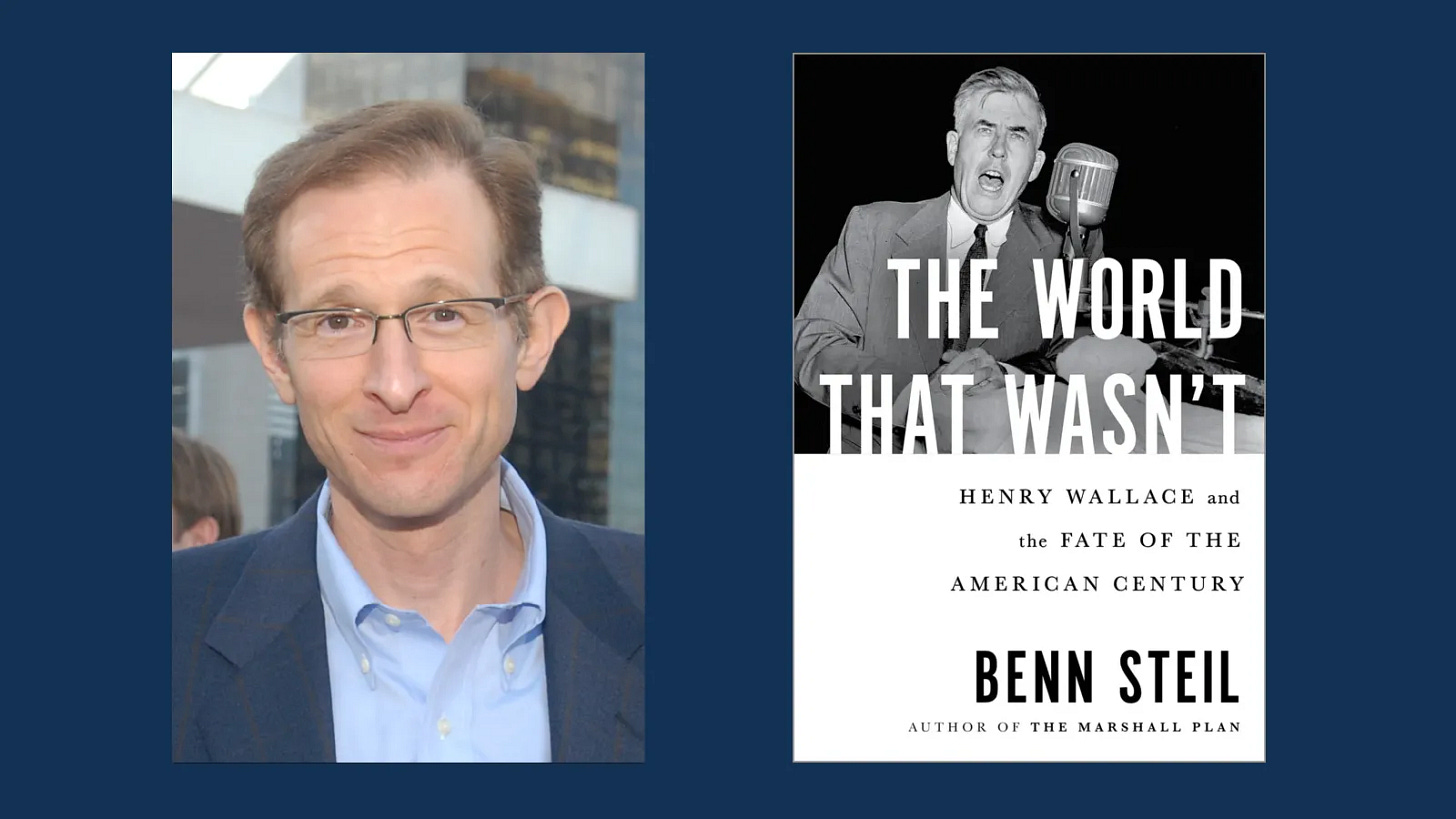

Historians and Cold War enthusiasts have mythologized that 1944 Convention to death with no clear conclusion: was Wallace—a progressive politician unbeholden to moneyed interests—cheated out of the presidency due to shady bribes and political machinations by Democratic Party leadership? It was Oliver Stone’s 2012 documentary, '“The Untold History of the United States”, that re-ignited and popularized the pro-Wallace position, which had remained irrelevant until Occupy Wall Street and other progressive groups coalesced around economic liberalism once again. Still, the documentary had its limitations given Stone’s outsized reputation with bending historical truth and its lengthy runtime. It may have told afresh the shady events of that Convention, but it didn’t fully revive Wallace as a revolutionary force that a movement could/should gather around. That didn’t stop Council on Foreign Relations in-house historian and economist Benn Steil from writing an overwrought paean celebrating the early Cold War against Henry Wallace’s World That Wasn’t.

Steil references Stone and Wallace’s depiction as a leftist hero as justification for writing this incredibly untimely biography, which amounts to thinly veiled reactionary propaganda—a post?-post-revisionist history. Steil makes it clear that Wallace, had he become President, would have delayed the beginning of the Cold War, which would have led to disastrous effects. In other words, the reason Steil is re-awakening this long dormant debate over Wallace and the 1944 Convention is contemporary pre-emption vis-à-vis China/Russia/Iran via historicism. After all, “a failure to resist and deter Joseph Stalin would likely have meant Soviet domination of northern Iran, eastern Turkey, the Turkish Straights, Hokkaido, the Korean Peninsula, Greece, and all of Germany.” It’s surely a good thing that a superpower didn’t dominate any of those places to ill effect…

The book’s basic premise is an unfalsifiable argument: ‘Well, folks, good thing we avoided what could have been’, rather than an honest reckoning with what actually happened: bipolar superpower geopolitics, proxy wars, nuclear arms buildup, arbitrary country divisions, and the establishment of a massive global police/surveillance state. “And even if,” as Steil irrelevantly argues, “the Cold War had only been delayed by a Wallace presidency, postwar history would no doubt have been very different because of it.” Such begins Steil’s ‘takedown’ of Wallace, this time with the use of Soviet archives and not from a hagiographic viewpoint. (John C. Culver and John Hyde wrote the definitive Wallace biography over two decades ago, which Steil heavily relies on but acknowledges as too biased.) Therefore, Steil is setting the record straight damn it; after all, writing this on the flimsy prospect of being a preventative war argument taking on a fifteen-minute segment from a decade-old Oliver Stone documentary wouldn’t hold up, no matter how lucrative those CFR writing and research grants are.

Right away, the reader is stuck in the awkward position of having to read a ‘biography’ of Wallace whose author can’t decide between pity or condescension; so, he opts for both. Steil pities the farmer and successful seed businessman who got mixed up in the rough and tumble of Washington politics while contemptuously describes how Wallace was duped by Soviet agents, communist-friendly Democratic Party aids, and Eastern Mysticism—as if to say Anglo-American agents, corporate-friendly reactionary aids, and Christianity was desirable. Steil pities Wallace’s childlike naivete while admonishing that same innocence, which led to crazed ideals like decolonization/anti-Imperialism, equal pay for equal work, anti-monopolistic capitalism, and postwar collaboration. The way Steil performs this anachronistic dance is through disproportionately discrediting Wallace on other issues so that these ideals are obscured to the point of nonexistence.

In telling the story of Henry Wallace, Steil selectively focuses on events that display Wallace’s lack of knowledge and how his own ego and wacky ideas supplanted any form of reason or leadership capabilities. Steil prefers chapters focused on solitary moments—such as the Secretary of Agriculture role, the Roerich group, the Vice Presidency, and the Asia trip—rather than overlapping events. This approach highlights Wallace’s actions as inattentive, poorly conceived, and poorly implemented. Steil, trained as an economist, doesn’t write compelling historical stories, which tends towards stilted prose, and instead opts for summarizing other biographies and primary sources, mixed in with light quotations, and held together with editorializing glue. These content measures were designed not only to further discredit Wallace by decontextualizing the history, but also to boost word (and endnote) count and legitimize the text itself as a history book.

Whenever Roosevelt or Wallace are quoted, Steil often paraphrases many of the words between several quoted ones, which can make any historical figure sound however unpleasant they want. Regarding his editorializing, for instance, Steil would often write things like, “[Roerich] may, too, it seems, have offered to report on British activities in the region,” which he even writes in the endnote section is an unsubstantiated story. This happens one too many times (as is his use of italics in both his words and others’ as well as the words “opined” and “in fact”), which makes one feel as if many of the claims with qualifiers offer corrections in smaller print in the back. But that doesn’t stop Steil from offering a Fake News-esque claim that many don’t realize was quietly excised when the story stuck.

Steil recounts Wallace’s biographical events leading up to the Convention as if forced to under genre constraints. He recounts his Iowa childhood: grandfather ran a famous farm magazine, which his father had taken over before becoming the Secretary of Agriculture under Harding and Coolidge. Wallace, as a young man, was more interested in corn breeding and large-yield hybridization. From his teen-age years onward, Wallace was more into spiritualism than Christian orthodoxy. Steil blames religious and philosophical movements in the first decade of the twentieth-century, plus a basic misreading of William James, for making Wallace open to cooky ideas disguised as mysticism and other spiritual matters, which he reminds readers in every chapter to discredit any of Wallace’s ideas as utopian, unreal, or downright stupid.

When Wallace was in his thirties in the nineteen-twenties, his politics was based almost entirely on agriculture: he wanted more isolationism and self-sufficiency since export tariffs and lending would hurt farmers by raising their costs. But in 1930 Wallace had shifted gears by calling for international trade deals to cut tariffs and for American farmers to embrace foreign affairs. Steil calls out this political change of mind by calling Wallace a “born again internationalist” who wanted a healthy “one-world” to work together. For Steil, as is apparent on many issues, a changing opinion means confusion of ideals and ill-conceived plans rather than reacting to external socio-economic forces, which the Great Depression can certainly count as.

Roosevelt reached out to Wallace, among other Midwest farmers, for his opinions: at this time, Wallace wanted a domestic allotment plan to lower supply and output to avoid state socialism ruining the independent family farm—Jeffersonianism over Leninism. Having been taken in by Roosevelt’s mastering of “the art of displaying warmth and interest,” which Steil uses to discredit both the naïve Wallace and cunning Roosevelt, Wallace’s ideas were used to pitch rural farm votes and presidential endorsement in Wallace’s magazine. Wallace, never a Democratic voter until he blamed Coolidge and Harding for his father’s early death, was skeptical of Roosevelt’s progressiveness.

Thereafter marks Steil’s shift from chronological events to de-contextualized singularities, starting with Wallace’s appointment as Secretary of Agriculture in 1933. For instance, in a history book covering a New Deal politician by an economist, this text does little to explain the New Deal. Steil instead focuses on one of Wallace’s bills, the Agricultural Adjustment Act, which was an ambitious omnibus package to help struggling farmers reeling from the devastation of the Great Depression. The Act subsidized farmers overnight but failed to help the poorer farmers that owned less land, who received less. As one of many acts designed for the New Deal, Steil could have provided more context, given his expertise, rather than hyper-focusing on one act detached from the rest. He instead uses the opportunity to highlight his take on Wallace’s poor handling of managerial and administrative duties while also slandering his ability to have intimate relationships with others, including his wife. Perhaps Steil went too far in casting out his opinion on this seed man.

Wallace’s second stint as Secretary of Agriculture is almost entirely omitted.

While half of this book deals with Wallace’s inability to have succinct ideas and communicate them effectively as a political or spiritual man, the other half goes after Wallace’s characterization as a useful idiot for the Soviets.

Steil claims that the Soviets duped Wallace into believing in their reforms and agricultural technical advancement in the nineteen-thirties while not taking all the atrocities into account. But he fails to mention that powerful reactionary magazine tycoon Henry Luce, who Steil mentions several times uncritically, made the exact same pronouncement at the same time in Life and named Stalin Time’s Person of the Year, twice, in 1939 and 1942.

When Wallace rallied for international cooperation via lower trade tariffs, according to Steil, that was an outgrowth of his support for Stalin’s collectivization. But in 1933, as Steil mentions, Wallace had rejected closer diplomatic ties with the Soviet Union because it would cause chaos for capitalist countries. No matter whether Wallace leaned towards isolationism or free trade, Steil labeled any decision as the consequence of his own political naivety and vanity.

The heft of this book is in three unequal incidents: the Roerich group, the 1944 Convention, and the Open Letter to Stalin.

Nicholas Roerich was a Russian mystic and artist who ran a museum in New York that Wallace liked to visit. The Roerich Group was committed to environmentalism and feminism, aspects that Steil purposely avoids mentioning more than once. He spends a majority of the chapter discussing their efforts in creating a “New Country” based in Central Asia, trying to curry favor with any powerful government that would fund them. The climax of this brief period in Wallace’s peripheral life resulted in a failed botany expedition led by Roerich. In perhaps the most desperate chapter at painting Wallace in a negative light, which includes Wallace as a background extra at most, Steil tries every possible two-to-three-degrees of separation game to “prove” how Wallace was connected to the Soviets, even proposing conspiracy theories like the USD bill’s eye of the pyramid and Latin phrase. In what amounts to a sixty-page chapter with two-hundred-and-eighty-one endnotes, Steil does little more than clarify Wallace’s support (while he was busy with the AAA and other New Deal programs, mind you) of Roerich’s cooky goal in the first half of the nineteen-thirties. There was a reason previous biographers limited this story from Wallace’s life, which ends up being a giant waste-of-time nothingburger.

After the Roerich gossip, Steil tells the lead-up to the 1944 Convention via Wallace’s time as Vice President during Roosevelt’s third term. After first de-emphasizing the powers that the VP holds, which is slim, Steil nevertheless argues that Wallace’s embrace of cooperation among Allied powers was dangerous. He overemphasizes Wallace’s op-eds and public speeches, which, as typical political statements go, called for ambitious projects and goals. He underemphasized the popularity of the Century of the Common Man speech, which introduced the concept of people’s rights into the American Century formulation, which Luce purposefully doesn’t include—moreover, Luce uses human rights as a double-standard talking point to paint certain governments (ones not supporting the US) in a bad light. Roosevelt sent Wallace on a trip to the Soviet Union and China on an ally fact-finding mission. Political niceties in this instance are suspect, according to Steil. In retrospect, one can easily dismiss public support for the Soviets during WW2 as being eerily cozy to an evil regime, but this anachronism doesn’t compute for a Vice President at the time needing to shore up diplomatic and military support against an Axis behemoth. In one of the most prescient observations at the time, Wallace warned against double crossing the Soviets after the war, which could lead to another war. Steil, even with hindsight, uses this as a moment to mock Wallace’s ability to make statements that the Soviets liked.

When Wallace came back to the US after his Asia trip, the Democratic National Convention was months away. Much of this story, which is endlessly (and for good reason) repeated and mythologized by everyone, hinges on Steil’s privileging the different sides of public support: simply, support for Wallace was the result of shady politicking while support for Truman was legitimate. A Gallup poll before the Convention revealed overwhelming public support for Wallace. Steil discredits this by claiming Truman wasn’t well known enough, despite being a popular Senator for ten years and landing the cover of Time magazine. When the Convention began, the massive support for Wallace from both voting and non-voting members was narrated using negative language: there was a “crush at the doors,” it was “invaded,” they were “illegally pushing delegates,” and there was “purposeful, orchestrated mayhem.” As if political conventions were clean, tidy, and noiseless beforehand.

Steil claims, without proof, that the over-capacity crowd was used to coerce delegates to vote for Wallace using physical intimidation. As the tale goes, the first day of voting led to Roosevelt’s fourth presidential nomination. At the end of the day, with delegates shouting for Wallace’s nomination and the organist spontaneously playing Wallace’s home campaign song, the gavel banged for the day’s events to end before a vote could occur, which, by all accounts, from pro- and anti-Wallace observers, would have led to a Wallace nomination. Then overnight, the real nomination process was happening behind closed doors among party bosses in hotel rooms, which led to a Truman win the next day. (Steil can’t help himself even when describing that the victorious Truman had organic support while Wallace’s votes were from a CIO-led conspiracy.) Historians have claimed that this is where political appointments were handed out for delegate support, which Steil vehemently argues against. He claims that there is no evidence of bribery or job arrangements taking place.

Steil uses precise language here: in referencing David McCullough’s biography of Truman, who wrote that “ambassadorships or postmastership jobs were promised”, Steil argues that “no such promises were ever made. But if the legend is, in fact, false, how can we know that?” He gave three reasons: first, to dismiss the ability of party bosses to hand over appointments without Roosevelt’s will; second, to diminish the ability of postmasterships to be handed out; and third, most crucially, to show how “the historical record virtually proves the legend’s falsehood.” He records that “of the fifty-five delegation chairmen, none became an ambassador (or postmaster) under FDR” and “of the 1,176 total delegates, only a single one became ambassador under FDR”, while “under Truman, in total, four delegates from four different delegations became ambassadors”. Notice the language used: “under FDR”, barely anything. But these votes were for Truman and not Roosevelt, so why would that matter? Also, it was specifically the delegation chairmen and delegates who didn’t receive appointments.

Fair enough, but Steil avoids mentioning (known as lying by omission) the other appointments handed out: Edwin Pauley, Convention director, was appointed to an advisor position for financial agreements in postwar Europe; Samuel Jackson, Convention chair and the one who banged the gavel to adjourn before Wallace’s surefire nomination, was appointed to a National commodities and exchange governorship; Robert Hannegan, DNC chairman and the one who told Jackson to bang the gavel against the delegates wishes, was appointed to Postmaster General by Truman; Paul McNutt, who gave his votes to Truman after the second ballot adjustment, became High Commissioner and then Ambassador to the Philippines; and even Leonard Reinsch, radio manager of the Convention who shut down the organist playing Wallace’s home campaign song and then blasted music to drown out Wallace chants after the gavel banged, was given a comms position in White House.

From there, Wallace’s political career began its decline. To make sure he wouldn’t leave the party and take away votes in the election, Roosevelt assigned him Secretary of Commerce, which would also ensure Wallace wouldn’t have a foreign policy position. As wartime turned postwar, Wallace wanted to deepen economic ties with the Soviets, who feared capitalist encirclement. Wallace, the final New Dealer left in the cabinet, was fired by Truman over his views that the Soviets and Americans both had spheres of influence to defend and that an Anglo-American alliance would lead to a superpower war.

Wallace landed an op-ed job disguised as an editorship for The New Republic, which he used to continue arguing his Soviet cooperation viewpoint and prepare for a presidential run in 1948. He also argued that the US was heading towards a state beholden to militarism and bureaucracy in the name of financial interest, which is exactly what happened that year with the passing of the National Security Act.

The climax and gotcha of this book is an “Open Letter” Wallace wrote to Stalin in 1948, which led to a response from Stalin. In typical fashion, Steil claims, without substantiation, that “Stalin’s last draft message, therefore, constitutes documentary evidence of his personal involvement in the writing of Wallace’s ‘Open Letter’.” What’s the proof? That in a handwritten note scribbled by someone other than Stalin, it said to include the words “excluding any discrimination” for a point about resuming unlimited commerce between the two superpowers. That’s it, three words qualifying a larger point, and even Steil “does not know if or when this, or a similar, message was communicated to Wallace.” This is all quite a stretch to claim that Stalin was personally involved with Wallace’s drafting of the letter.

Such connection-building is crucial to Steil’s overall argument about Wallace, which he connects to contemporary events. He calls the “Open Letter” chapter “Collusion,” by arguing via MSNBC/Never Trumperisms that several people who worked for Wallace were also friendly partners with Soviet agents. Therefore, Wallace is utterly compromised. Thomas W. Devine already wrote Henry Wallace's 1948 Presidential Campaign and the Future of Postwar Liberalism, a revisionist to the revisionist Wallace book a decade ago, making nearly the exact same argument about Wallace’s loony ambitions. (Incidentally, John Lewis Gaddis, the godfather of Cold War history writing, urged Steil, a non-historian and non-political scientist, to write this book.) Why else would a CFR member—whose organization promoted Kennan’s containment theory and the Marshall Plan—undertake this project if not to stoke a modern-day Sino-Russian Red Scare? Like the prosecutor played by Jason Clarke in Oppenheimer unnecessarily questioning Oppenheimer’s loyalty for a higher-up’s political gain, Steil is doing the same chimpish mud-slinging that is serving positions of power. In this CFR jargon-fest, more historical figures will be dragged back for scrutiny, forced to reapply for their clearance credentials, and hounded over tired, rehashed narratives—pushing us ever closer to oblivion.

Take these concluding remarks for example:

Wallace misunderstood ‘peace’ as a policy choice—a policy choice which Harry Truman, under malign conservative influence, allegedly rejected in favor of an unnecessary and devastating Cold War with Russia. Peace between conflicting sovereign nations is not a policy choice, however, but a state of affairs which obtains when each sublimates the will to act for the purpose of avoiding war. When sublimation is unilateral, it is not peace, but appeasement. And given Stalin’s designs on Turkey, Iran, Greece, Germany, Manchuria, and Korea, the only alternatives to Cold War were hot war and appeasement.

It’s a good thing the US didn’t also have designs on those countries.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button at the top or the bottom of this page to like this entry, and use the share and/or res-stack buttons to share this across social media. Leave a comment below if the mood strikes you to do so. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t done so already.