Weekly Reel, June 15

News: Covid's Impact, 007, Streaming Plateaus, Review: "Certified Copy," Essay: The Sino-Hollywood Relationship.

A study by UTA IQ titled “Forever Changed: COVID-19’s Lasting Impact on the Entertainment Industry” surveyed adults on the impact of people staying home more often post-lockdown. A predictably large amount of respondents reported higher amounts of entertainment viewing during the pandemic and will continue to do so in the future. But the real change, which the lockdowns hyper-accelerated, is that the consumers used multiple streaming platforms and that a third of them will subscribe to more in the future (implied here is the linear inverse of accelerated cord-cutting). In addition to this, many of the respondents hardened their habits towards these changes. Joe Kessler, global head of UTA IQ, said that “the key issue now is whether this gives way to a more enduring shift in behavior and expectations. What consumers are telling us is that now that they have formed many new habits, they won’t let them go.” What are the new habits you formed and strengthened thanks to the pandemic?

“Cinema chains count on 007 to restore their Covid-hit takings” is the latest headline of many to come this summer as theaters begin to open and are in need a box-office savior. Last year this happened with Tenet, which I wrote about at the time, and this year it’s No Time to Die (September release date). Although the state of box-office earnings is more solid this year than last as proven with Godzilla v. Kong in April and A Quiet Place Part II these last few weeks, it doesn’t change the long downward trend of theatergoing that will always keep theaters in a lower yet awkwardly stable position financially.

Disney + and Netflix are seeing fewer than expected subscriber growth for three reasons: subscriber pull-forward (because so many more than anticipated consumers subscribed to streaming apps during the lockdowns in 2020, that left a smaller amount of potential subscribers in 2021), content squeeze (the lockdowns ended film production and now for a little while there won’t be enough new content to attract subscribers), and theater reopenings.

Certified Copy (Abbas Kiarostami, France/Iran, 2010)

Every film student has to watch Abbas Kiarostami’s 1990 Close-Up; it’s about the real-life story of a man who impersonated a filmmaker, deceived a family using this identity, but then was caught and stood trial for it. The amazing part is that Kiarostami casted the actual, real-life people and had them re-enact what had happened. In that way it’s a nice F for Fake-like balance between documentary and fiction showing how related the two supposedly mutually exclusive genres function.

Kiarostami continued this trend for another two decades on a dozen docufictions until teaming up with his old friend and French film actress, Juliette Binoche. As the publicity story for the initial idea of the film goes, Kiarostami told Binoche the synopsis of a made-up film (in true Kiarostami form, he recalled: “The very process of telling the story gave me the structure of the film.”) when she visited him in Iran, which over time grew into a fictional feature film. Kiarostami was compelled to write the script because of their friendship and his knowledge of Binoche’s sensitivity, vulnerability, relationship with her children, etc.

Certified Copy would became unique in Kiarostami’s film career in that it’s the first feature film he shot outside Iran with a mostly professional cast/crew. He previously opted for non-professionals to give the “docu-” part of his docufictions more weight. Although unclear exactly why he decided to shoot outside of Iran, it’s probably because of the generous yet complicated inter-government film grants in Europe. The funding of this film, for instance:

The €3.8m film starring Juliette Binoche was 70% produced by France via MK2, 20% by Italy (Bi Bi Films) and 10% by Belgium. Backed by the CNC with an advance on receipts, co-produced by France 3 Cinéma and pre-bought by Canal +, the title will be distributed in France and sold internationally by MK2.

Certified Copy tells a story about authenticity and imitation and how they can be the same. Binoche plays a French antique dealer in Tuscany who spends the day with a British writer, played by non-actor, baritone opera singer William Shimell, who’s in town to discuss his book, “Certified Copy,” which argues that authenticity in art is irrelevant given that there’s always a deeper level of derivation of anything supposedly original. (For example, wasn’t the Mona Lisa based on the original beauty of a real woman?) In typical European film form, the entire plot revolves around the two characters walking around and talking, mostly about art. But then the film changes tone when they go to a cafe and the owner mistakes them for a married couple, which they play along with and continue with and strengthen for the rest of the film. They pretend to be a married couple with conversations in both English and French. They argue as if they’ve been in a declining marriage for some time, where the husband is constantly absent because of work and the wife is having difficulties connecting with her son.

What I like and find refreshing about the film is its use of authenticating art through the representation of film as art. Although the two characters are not a married couple discussing their actual troubles, neither are the real-life actors the characters in which they are playing. So then which is more authentic?

Binoche in particular gives an amazing performance that is captivating and feels real to the point that, given the fact that Kiarostami wrote the script with Binoche’s relationship to her family in mind, it may actually be authentic in the way that the film defines the word. At some level, the artifice of dramatic film must still come from some deeper (and more authentic?) level of originality. Therefore what we’re watching is either completely original or a reproduction of an original, which is itself an original. But while this short review/summary may be complicating the story more than necessary, the film does a good job in staying grounded and not falling into the abstract-realm of disbelief that pulls one right out of the screen.

Certified Copy is available on the Criterion Channel and Amazon Prime.

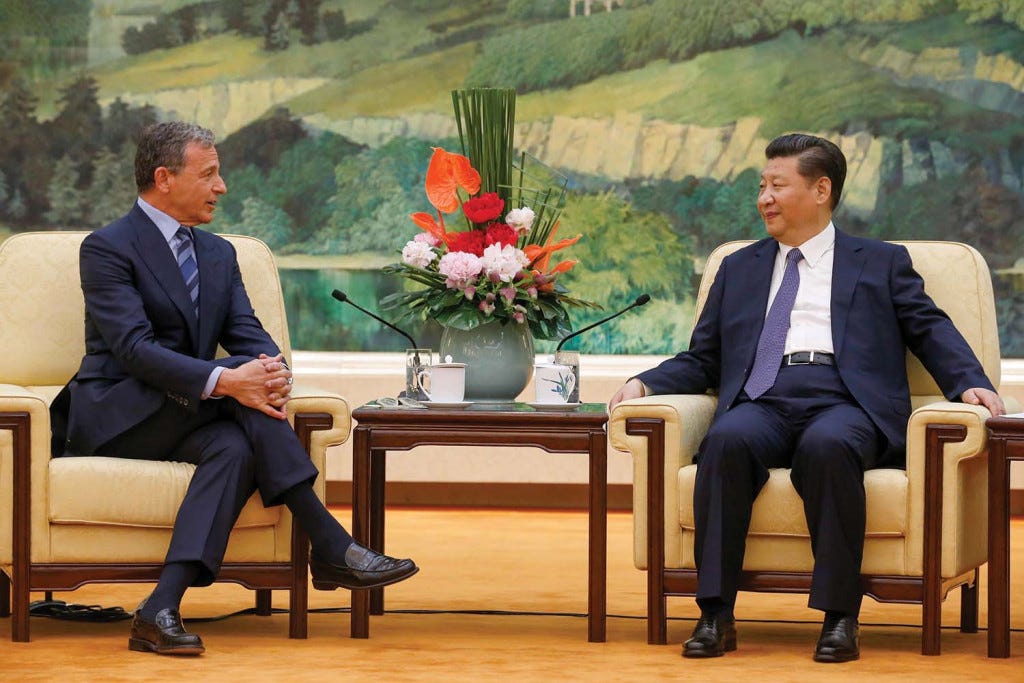

Essay: “From Deal Frenzy to Decoupling: Is the China-Hollywood Romance Officially Over?” by Patrick Brzeski and Tatiana Siegel

Disney was one of the early adopters of the rising Chinese middle-class market in the 1990s. Martin Scorsese released Kundun in 1997, a biographical film about the Dalai Lama, which was partly owned by Disney through their subsidiary Touchstone Pictures. Because the film featured the Chinese invasion of Tibet and oppression of their spiritual leader, China threatened harsch business consequences if released. After Universal passed on the film’s distribution, Disney did so through their Buena Vista Pictures Distribution. China immediately banned all business relations with Disney films until action against Kundun and its filmmakers was taken. Disney officially apologized for its release and Disney CEO Michael Eisner said (I imagine he was on his knees, hands clasped, grovelling, tears about to break…): “The bad news is that the film was made; the good news is that nobody watched it.” Then Eisner sent Henry Kissinger (yes that one) through that Open Door to China to normalize relations like Nixon did before. Out of the talks came the reinstatement of Disney’s film distribution in China, the deal to open a theme park in Shanghai with plurality Chinese ownership, and the complete silence of anything critical about the Chinese coming from a Disney-owned or branded product.

But for the last couple of years the Sino-Hollywood relationship has been changing. Most recently with regards to Chloé Zhao (director of Nomadland, born in Beijing) and Searchlight Pictures (distributor of Nomadland and owned by Disney) trying to play it safe:

Sources say that in late 2020, a Searchlight publicist persuaded the small, New York-based Filmmaker magazine to remove a quote from a 2013 Zhao profile in which the budding auteur explained the inspiration for her first feature film, Songs My Brother Taught Me, about a Native American teenager looking for escape from the tough conditions of South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. “It goes back to when I was a teenager in China, being in a place where there are lies everywhere,” she said. “You felt like you were never going to be able to get out. A lot of info I received when I was younger was not true, and I became very rebellious toward my family and my background. I went to England suddenly and relearned my history. Studying political science in a liberal arts college was a way for me to figure out what is real. Arm yourself with information, and then challenge that too.”

In most contexts, Zhao’s remarks — an ambitious young artist reflecting on the memories of teenage angst and rebellion that inform her work — would be innocuous. And if it weren’t already de rigueur for the American film industry, Disney’s behavior would be a scandal — the United States’ most iconic media brand, going out of its way to preemptively aid an authoritarian government in censoring an artist’s interview with an American media outlet. (Disney and Filmmaker declined to comment.)

But as it turned out, the studio’s efforts were for naught, while its risk assessment was indeed accurate. While the quote has been removed from Filmmaker‘s website, archived versions were unearthed in China shortly after Zhao’s best director win at the Golden Globes, setting off a social media backlash that prompted Chinese authorities to cancel the local release of Nomadland in April and expunge most mentions of Zhao from the internet. The controversy reached its zenith with the Oscars being fully censored in China, just as a homegrown hero was capturing the film world’s biggest prize.

All it took was a single line from a nine year old interview with a 21 year old filmmaker about her first film for China to cancel both a film’s distribution, which is ironically slightly critical of the American Dream and capitalism, and the Oscars. This comes at an interesting time in China-US relations punctuated by criticism of China’s influence in Hollywood and the pandemic:

As the U.S. film sector emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic — not to mention the Donald Trump administration and its aggressive trade war — the Hollywood-China relationship is at a crossroads. U.S. market share is on a downward trajectory as local fare is finding greater traction at the Middle Kingdom multiplex than Hollywood imports. (In 2019, the last pre-pandemic year of business normalcy, the Hollywood studios’ collective total revenue in China fell 2.7 percent compared to the previous year, the first such direct decline in a generation.) Meanwhile, Hollywood is facing criticism stateside for bending over backward to appease the authoritarian regime.

Amid a new climate of direct geopolitical rivalry with China, many analysts believe the U.S. studios will be lucky if they can retain the foothold they once had there, let alone make any meaningful progress toward expanding market access or growing revenue.

For the first time since Kunden it appears that the Sino-Hollywood relationship isn’t stable and actively declining over the cost of doing business with China’s demands for self-censorship.

Straight from the American/Hollywood business playbook, which, especially in the postwar years, unilaterally used its market influence to direct the flow of films distributed overseas:

Critics, often academics, argue that China has cannily leveraged its market heft to co-opt Hollywood’s global pop culture machine into effectively carrying the water for one of the country’s most important lines of strategic global messaging: that China’s rise as a global superpower is a benign or stabilizing phenomenon. To the suggestion that Hollywood isn’t in the business of art with an agenda, critics can take their pick of the dozens of films released in recent years offering direct critiques of the United States’ own foreign policy and social justice failures…

A summary of the Obama years and how Hollywood slipped into bed with the CCP:

Throughout the Obama era, Washington foreign policy consensus held that the best way for the U.S. to avoid dangerous conflict with a rising China was for the two countries to become indispensably integrated economically. The consensus in Hollywood, meanwhile, was similar but slightly different: The best way to get rich was to extend your business into China’s burgeoning consumer market as deeply as possible — whether by tapping into the country’s overflowing pool of outbound investment capital, or by establishing novel ventures that would ostensibly bridge the world’s two largest entertainment markets for decades to come.

On the Chinese side, Beijing deployed its standard playbook for playing catch-up in a high-sophistication industry dominated by the West: Crack open the door to the local market just wide enough to entice experienced foreign firms to enter into partnerships and joint ventures with local companies — required in many sectors under Chinese law in exchange for market access — with the ultimate aim of facilitating rapid knowledge transfer to the Chinese side while limiting the foreign players’ potential dominance. The cultural influence of American movies was never desirable to the CCP, but the power of Hollywood movie magic to pull in consumers was well understood and leveraged strategically to fuel the construction of China’s domestic infrastructure. Indeed, a historic cinema building boom ensued, as China went from a little over 6,000 screens in 2010 to over 75,000 by the end of 2020.

In regards to streaming apps/companies, it appears they won’t be getting into China anytime soon because of the companies’ dependance on directly owning the content platforms and ability to collect consumer data rather than selling foreign distribution rights and/or co-owning theme parks, which is the business Hollywood mostly does with China:

China currently forbids foreign ownership or investment into any video platform operating within its borders, so any meaningful trade concession in the category would require a rewriting of Chinese law. The country’s stance on consumer data also is highly protectionist, while technological independence is one of Beijing’s central policy priorities. Together, such factors augur direly for U.S. streamers, analysts say.

I have no predictions because any slight incidence, like with Kundun, can send the relationship in any direction, but it certainly appears that the relationship isn’t sustainable in the long run and the American film studios will have to accept their losses, which for years was inflated from the red into the black by the Chinese middle-class. So with most stories currently unfolding, all we can say is we’ll see what happens next.