First with some news:

Covid + Streaming ≠ Death of the Theater (yet): Warner Bros. released Godzilla V. King Kong in theaters and HBO Max simultaneously. The film will perhaps make $100 million at the domestic (U.S. and Canada) box office and is nearing $300 million worldwide. Only 55% of American theaters have opened, most still not in the big LA/NY markets. Warner Bros. plans on returning to a theatrical-first release after the pandemic, but right now plans on releasing all summer blockbusters simultaneously. Although the confused and delayed Tenet theatrical release didn’t turn out great last summer, audiences are now willing to go to theaters, especially for the ‘big-loud’ films. We’ll see.

Sony Pictures sold its first pay window rights (meaning films after their theatrical and home entertainment distribution) to Netflix instead of starting its own streaming app like the other major film studios. Netflix can exclusively stream Sony’s blockbuster franchises, like the Jumanji and Bad Boys films, and choose from Sony-subsidiary Columbia Pictures’ massive catalogue, which includes Once Upon a Time in Hollywood and others. It also (most importantly) means that Netflix has access to the most popular Marvel character, Spider-Man, after Disney pulled all of their Marvel content to stream exclusively on Disney +. Disney has been fighting for the rights to Sony’s firm hold on Spider-Man since its acquisition of Marvel in 2009, and came close in the last few years when the studios worked together on Homecoming and Far From Home, but now with Sony’s commitment to Disney’s biggest (and only realistic) streaming rival, those chances have dropped considerably.

Italy officially transitioned from government censorship to industrial self-censorship. They will set up a commission “of film industry figures, as well as education experts and animal rights activists” to review every film’s classification. This doesn’t noticeably affect anything for the English-speaking film market. I just thought it was kind of interesting.

Another Round (Thomas Vinterberg, Denmark, 2020)

Four days into filming Another Round in 2019, director Thomas Vinterberg’s 19 year old daughter, Ida, was killed in a car accident. Vinterberg took a week off then returned to finish the rest of the shoot. He revised the mood of the film after returning, changing it from being playful to life-affirming.

The plot of the film is about a high school teacher, Martin (played by Mads Mikkelsen), and his three colleagues who decide to test Norwegian psychiatrist, Finn Skårderud’s, theory that humans are born with a blood alcohol level 0.05% too low. Martin arrives at this decision when he finds out that his life was on a slowly declining autopilot. His wife is more of a long-term roommate and his two sons don’t find him interesting (Ida was originally supposed to play his daughter, which would have been interesting. In fact, the school they filmed at was Ida’s high school and they used many of her actual classmates. Some part of her was still physically in the film.) But the film takes the mid-life crisis trope and gives it a more sincere touch than the gimmicky buddy-comedy films that usually deploy it.

The story, as Vinterberg discussed in interviews, is about life and finding it for oneself. Although the dangers of alcohol and its excesses are evident, it plays an ambiguously important role for humans. For example, in the film we watch short clips of drunk statesmen, references to Churchill’s drinking, etc. But also we see humans becoming more open and free, which in a film about high school teachers provides a further ‘naughty’ layer when we see them drunk in class. The film does a good job in neither turning towards pure playfulness, as was the original intent, nor self-pity. It slices toward the center of the two, which is where the life-affirmation core is found.

In the end, one isn’t left with the depressing feeling of failing to find one’s own freedom. But rather the opposite. That we have the ability, that it isn’t entirely good or bad, that we can.

Available to watch on Hulu in the US.

Nominated for two Oscars: Best Director and International Feature Film.

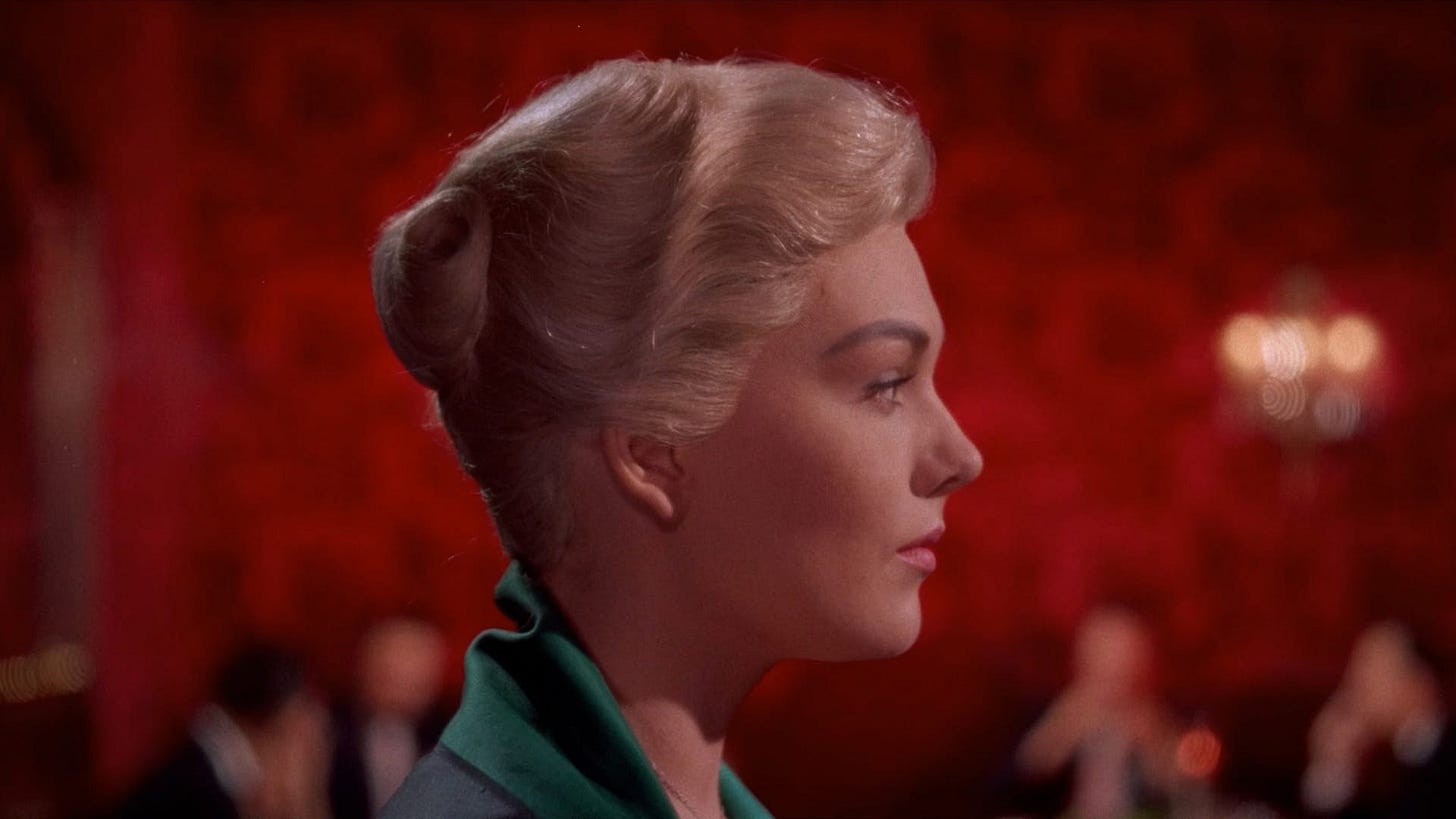

Retro-Review: Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, USA, 1958)

Depending on whatever film-ranking list you use, Vertigo will most likely appear as one the top two films of all time alongside Citizen Kane and followed by either Tokyo Story or 2001: A Space Odyssey. But this is coming in another post.

Vertigo is the Film of films. It’s most filmmakers and critics favorite Hitchcock film and has aged better than his other films. Apart from a couple plot issues that have been thoroughly denounced over the years (the flashback after Scottie meets real-Judy and the vertigo-contrivance), the story remains impactful and absorbing nonetheless.

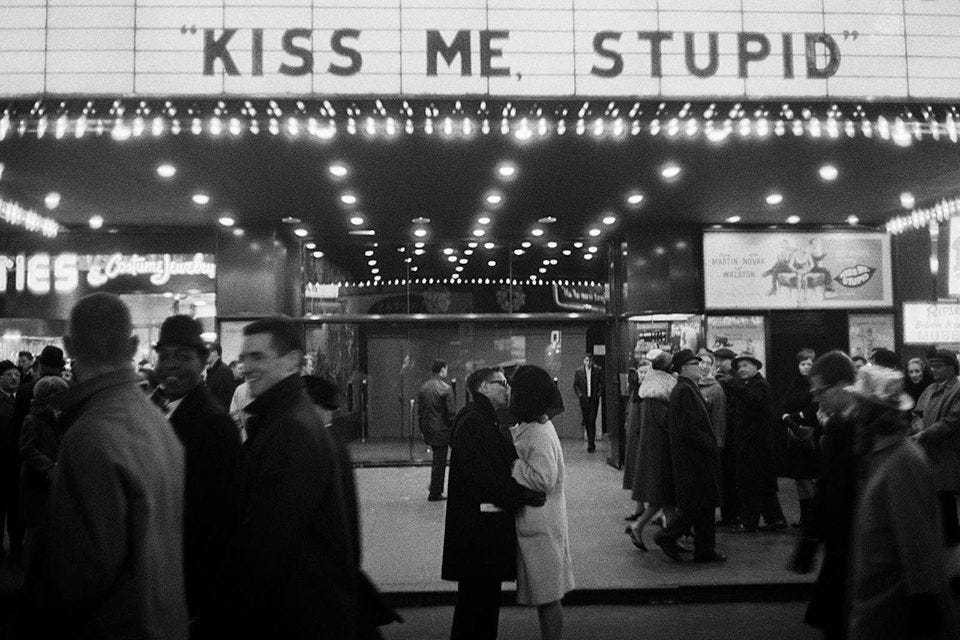

It’s a film about a guy who is obsessed with the representation of a woman who pretends she is another woman, who, spoilers, is played by another woman. All three women (Madeleine, Carlotta, and Judy) are played by Kim Novak and are technically the same woman, just with multiple layers of an Inception-like representation within a representation. The guy, Scottie (James Stewart), is obsessed with Judy playing Madeleine, while Madeleine pretends to be Carlotta. All three women end up dead by the end of the film, of which Scottie witnessed two-thirds.

The sharpest line of interpretation is of the sublime, of the perfection of beauty and the fatal nightmare of fulfilling one’s desires. Halfway through the film, Madeleine is thought to have fallen to her death, which sends Scottie into a depression and makes him obsess over her more. Then he sees, stalks, and meets Judy, not knowing she actually played Madeleine, and in so doing splits the film’s pov into Judy’s. From then on, we see Judy come to terms with her complicated love for Scottie as he thinks he loves a different woman. Only through her transformation back into the dead Madeleine does Scottie fully embrace her; happy ending. But the film keeps going unfortunately. Scottie finds out Judy was actually Madeleine, confronts her about it at the place Madeleine died, then Judy throws herself off the tower from (probably) seeing the spectre of an impossible relationship.

Vertigo remains one of the best non-sci-fi film about what it means to be a representation of a human with all its messy desires. And for that reason it’ll be a perennial viewing for many as they watch a person succumb to obsession/perfection.

Article: Not Buying It; As films and film culture face brutal and witless change, love of the art form can be radical and sustaining.

In an article for Film Comment by Michael Koresky, he outlines the need for resistance as a feeling of decline and impending doom comes down upon the film industry; to fight back instead of expecting the inevitable collapse. Here’s his short list of present ailments:

The studios have become a cohort of entirely risk-averse bottom-liners, resulting in an arsenal of franchise products aimed at the wallets of mostly teen boys, but also their infantilized parents, in a natural progression—or perhaps the endgame—of where the business has been headed since the mid-’70s. This sense of homogenization has been dangerously compounded by the fact that Disney is in the process of all but taking over the industry, its gut-busting portfolio including not only Pixar, Lucasfilm, and Marvel, but also, as of just last year, the studio no longer to be known as 20th Century Fox. At the same time, the streaming revolution has been ever so gradually monopolized by a handful of goliaths—Netflix and Apple, in addition to the Mouse House—desperate for subscribers to help them break even, churning out the kinds of mega-entertainments they hope can compete with (and one day replace) the big-screen experiences we once thrilled to. In related bad news for the health of a culturally and economically diverse society, in November 2019, the United States Justice Department moved to overturn the 1948 Paramount Decree, the court decision that split up the studios’ monopolies on U.S. film exhibition—a landmark in antitrust lawmaking and a bedrock historical point for anyone who took a film studies course over the past half-century. That postwar decision came at a time when television was beginning its march toward cultural domination; that the reverse is happening as we face the very real threat of streaming-service takeover says a lot about a political moment shaped by deregulation and corporate coddling. Understandably, it makes mainstream cinematic culture seem as dubious a prospect as it ever has in our lifetimes.

Basically, the streaming giants become more powerful and less diffuse as more customers choose that over cable and theaters, which in turn is suited best for companies like Netflix, Disney, Amazon, and Apple, which have the volume, capital, or prestige required to compete and/or dominate. And what gets lost is the ability of independent productions, historically financially risky, from being made in favor of safe franchise bets. These non-studio backed independent productions, sometimes led by an auteur, are then picked up by one of the aforementioned companies for their auteur-as-brand image, for example with Netflix producing Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman.

As a result of this trend, firmly-held spaces for independents are dwindling because now they don’t get to share as much space in the major film companies:

Independent traveling exhibition setups for films of uncommon shape and form, such as Argentine filmmaker Mariano Llinás’s Sociedad de Exhibidores Transhumantes; itinerant showcases like Acropolis Cinema, which runs Locarno in Los Angeles; and dedicated specialty streaming services like MUBI will prove increasingly invaluable. So will publications like Film Comment, which continue, against all perceived odds, to grow a readership and fan base despite their steadfast devotion to art, form, and substance rather than the drummed-up PR narratives and hot-new-thing stories that have taken over much of what’s called entertainment journalism. Meanwhile, the larger nonprofit arts institutions—festivals, museums, and devoted organizations like the one that publishes the magazine you’re currently holding in your hands—will become even more important for the continuing education and understanding of cinema as the gap grows ever larger between the art and the commercial enterprises that purport to buoy it, but in reality threaten to swallow it up.

The problem with the sentiment here is that Koresky reminds the readers of Film Comment to support institutions and media sites they most likely already support, given the type of audience. And his argument relates to the larger problem within the Scorsese v. Marvel, cinema v. visual entertainment argument in general, which is obsessed with talking about the decline of cinema and need for a reinvigoration in various guises. But if we’re talking about American cinema, then we’re talking about one that has always been controlled by capital. If European, as the Americans use for examples of peak mid-century independent productions, then we’re talking about multi-country production partnerships using government grants to fund the arts. None of this is bad or wrong, it’s just to say that this ideal of cinema as independent and artistically free has never been the case nor will ever go away in its small-service, some may say elitist (though not as a pejorative here), function. In general the auteur is cinema’s exception to the rule, whereby the rule is safe bet, studio/capital-backed blockbusters. And Koresky knows this, which is why he ends his essay with a shoulder shrug and movies-will-progress-anyway attitude.

But also I’m sympathetic to this argument. I would like cinema and the ideal of movies to live on in their fullest capacity, which will most likely be through curated, (again) elitist, non-democratic spaces where art is the focus. No algorithms, no quotas, just film as art, as Scorsese, Koresky, and others are fighting towards. This has always required a certain level of snobbery and selection that the so-called masses denounce, but that’s how film will progress: by maintaining it’s undemocratic, Cannes-atmospheric characteristics of visionaries and unabashed highbrows for as long as possible.