Some News:

ArcLight Cinemas and Pacific Theatres (owned by the same parent company, Decurion Corporation) are closing, which really sucks for Los Angeles film culture. Although the smallish chain only operated 16 theaters, they helped define and shape the local cinema scene at the Grove, in Sherman Oaks, Hollywood, etc., especially since the iconic Cinerama Dome, which opened in 1963. And this may be the reason why they failed to survive longer than the national chains, which received more stimulus aid and able to operate in markets that opened sooner than in Southern California. Anyway. I remember seeing Inside Out, The Wolfpack, and Mad Max all together on one hot summer day with my friend at the Pacific Theatre in Northridge, which was great until it got to the point where I had to eat one of the most-likely expired hot dogs for sustenance because too much theater popcorn leads to a vicious cycle of dehydration-thirst-bathroom (then back to dryness again), requiring large amounts of XL-size sodas or Icees. Am I now expected to do that in an AMC or Cinemark? No thanks.

Amazon is going to spend almost half a billion USD for the production alone on season one of their Lord of the Rings series. After picking up the rights to Tolkien’s world in 2017, Amazon will finally be developing content set to take place thousands of years before the events in the Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. This will be by far the most expensive series ever produced, set to reach over one billion USD from the advertising/publicity in addition to the amount already used to purchase the initial rights (250 million USD).

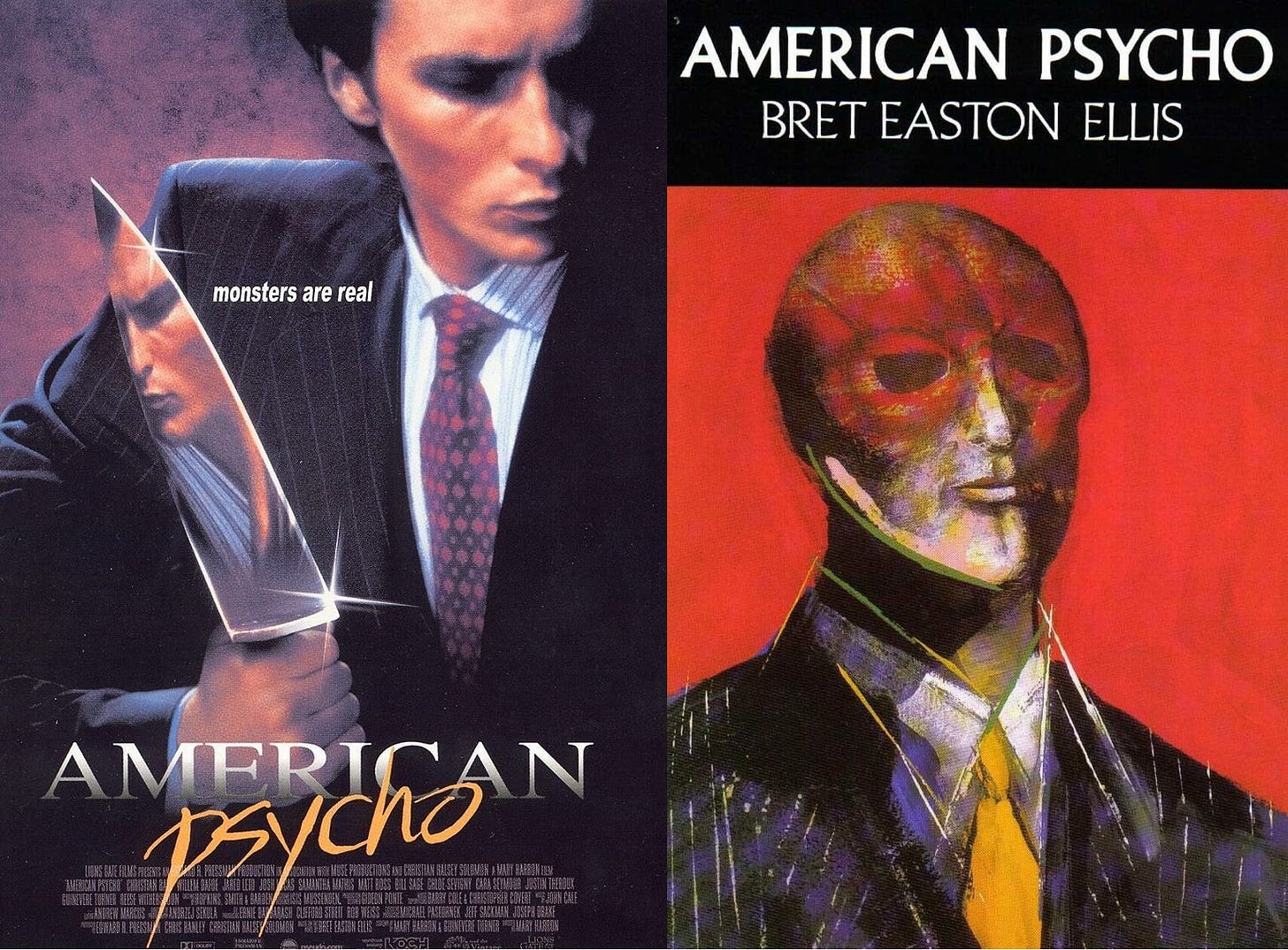

Retro-Review: American Psycho, Book v. Film

As can be seen from the two images above, the main difference between the American Psycho book (1991) and film (2000), is in the characterization of the narrator and AP himself, Patrick Bateman. In the film, left picture, Bateman is played by a young and charismatic Christian Bale, who supplies his own charm to the character no matter how emotion-less he performs it. But in the book, Bateman is soulless and completely inhuman. His only charisma is what the reader would like to add because the text offers none.

I had the misfortune of being born after the book’s release as well as growing up interested more in films than books, meaning I saw American Psycho (circa 2011) well before I read the book (just this last month, 2021). I read the book imagining Bale as he would have played the character with all his nuances/subtleties, which may have been useful in some parts but otherwise provided me with an unconscious image of Bale-as-Bateman that was hard to dismiss. Nonetheless, book-Bateman is not difficult to imagine because he’s simply devoid of humanity. If you’ve read any of those short reviews of commercial products that seem to all sound the same, use the same descriptions, then you can easily imagine book-Bateman using this basic formula: Bateman = Copywriter Text + Armani x Blood.

[Unavoidable plot summary and background:] Bateman works at an investment bank in Manhattan in the late 1980s. At that time, Yuppie culture (young urbanites) in the city and especially banking industry was rampant and hip because of the Reagan deregulations that helped hand over the country to the bankers. Also from this culture, a conservatism of conformity and 1950s nostalgia (e.g. Back to the Future) took over as a backlash to the proceedingly dominant non-conformity. In short, it provided the country with these monsters of commercialism that saw Donald Trump and 1980s Genesis as their idols (I always suspected a connection between the two). This concept at the time was taken to its fictional/figurative extreme in the form of a sexist-racist serial killer.

The book is essentially a collection of Bateman’s routines of daily hygiene, Zagat-guide restaurants and bars, torturing and murdering sentient beings, and brand name clothing and business apparel trends. The writer of the book, Bret Easton Ellis, had this to say about his inspiration for Bateman:

He did not come out of me sitting down and wanting to write a grand sweeping indictment of yuppie culture. It initiated because my own isolation and alienation at a point in my life. I was living like Patrick Bateman. I was slipping into a consumerist kind of void that was supposed to give me confidence and make me feel good about myself but just made me feel worse and worse and worse about myself. That is where the tension of "American Psycho" came from. It wasn't that I was going to make up this serial killer on Wall Street. High concept. Fantastic. It came from a much more personal place, and that's something that I've only been admitting in the last year or so.

Apart from Bale-as-Bateman, the pacing between the film and book are quite different out of their respective medium’s necessity. The book is more of a slow-burner that eases the reader into Bateman’s very graphically detailed killings while the film had to reach these beats much quicker. Another consequence from this is the juxtaposition between banal conversations like whether suit vests can be worn casually and biting off a woman’s body parts while she’s still alive, which I think is handled better in the book and less jarring. One of the reasons I really liked the book wasn’t just in the obvious indictment of the meaningless inhumanity of Yuppie culture, but because of the line being made literally connecting commercialism to a reduction of one’s identity, and not just one’s own unique identity, but also one’s identity as a human being. This is probably the feeling/intuition that Ellis described above.

Another interesting insight he made was between the book and the film, in which he gives his opinion (same interview from before) about the latter:

I don't know if it really works as a film. It's trying to take something that's not answerable and answering it in a medium that demands answers, which is film. By the very nature of the medium, it demands that you make choices. Where a novel can be unresolved, an unreliable narrator, it doesn't matter. I think Mary [Harron, the film’s director] a little bit was trying to have it both ways and kind of left it with an odd sense of displacement that wasn't particularly satisfying. That you can get away with in a novel.

For Ellis, the reason he doesn’t think it works as a film is because its very much meant to be a novel in which one reads, alone, the inner thoughts of Bateman instead of a somewhat charismatic representation on a screen. The ambiguity that Harron was trying to get away with was having both a definite reality of the events on screen (that Bateman actually killed and tortured these people) as well as having an unreliable narrator that was making it all up. In the book, this ambiguity is central to each person’s unique experience with the material while with the film, it’s a more collective experience that, as Ellis said, “demands answers,” which is why there’s still talk even today if Bateman in the film actually killed anybody. It should be noted that these discussions are not happening about the book.

In the one non-negative national review of the book immediately after its publication, Harry Bean for the LA Times wrote:

The novel subtly and relentlessly undercuts its own authority, and because Bateman, unlike, say, Nabokov’s unreliable narrators, does not hint at a “truth” beyond his own delusions, “American Psycho” becomes a wonderfully unstable account. The most persuasive details are combined with unlikely incidents until we’re not only unsure what’s real, we begin to doubt the existence of reality itself.

“Wonderfully unstable” would not be the words used to describe the film, which tends to cut either way between the poles of everything was real or not, and by definition, wonderfully stable. Although much more can be said between the two, I’ve got to go return some videotapes.

Article: How Big IP Is Driving the Streaming Wars

Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) streaming content through individual apps has been the biggest push by many of the big film studios and their parent companies since the rise of Netflix and other Big Tech (mostly Apple and Amazon) DTC streaming platforms, which has been exasperated by the mass closure of theaters. Central to that push is intellectual property (IP), which is a pre-existing, (ideally) popular property that is owned by one company and can be developed into various mass-media: films, series, theme park rides, merchandise, etc.

With the changing consumer habits favoring DTC streaming, the big film studios are moving semi-developed film ideas into series, DTC development. The best example of this is Disney’s ability to utilize a massive collection of Marvel characters and storylines, all existing in the same IP-verse that are easily spun-off from the films as their own series. Disney is now doing the same with Star Wars characters/storylines that it scrapped a few years ago because of Solo’s disappointment. They’re now gravitating over to the DTC division to be made into series because of the monster rise of Disney + over the last year and a half and subsequently massive demand for content other than The Mandalorian. Disney + had an immediate impact after its release in 2019 because of its near-monopoly of popular IPs (Disney Animation and Live-Action, Pixar, Marvel, Lucasfilm, etc.). But the biggest problem they found after its initial success was in creating new content for the app, which the film company didn’t have to previously worry about when they only released a dozen or so films theatrically each year.

Although popular IPs are vital for a DTC launch, it doesn’t help generate new subscribers. Original content is therefore needed to remedy this problem, but for a company like Disney, which stopped developing any content outside their half-dozen IPs, this process is more difficult. Instead, these companies are franchising creative talent. In an article for Variety, Joe Otterson writes:

Wholly new ideas are becoming rare commodities for all the focus on existing IP. But creative talent, too, is seen as a franchise-able force. Showrunner Taylor Sheridan scored a sleeper hit with Kevin Costner drama “Yellowstone” for the Paramount Network cabler. Now there’s talk of building the “Sheridan-verse” within ViacomCBS: The writer-producer has a “Yellowstone” prequel and the original drama “Mayor of Kingstown” starring Jeremy Renner lined up, with more on the way.

This seems to be more of a problem for the film companies that recently released their DTC apps, but not so much for Netflix and Amazon, which mostly produce original content and limit their series to as few seasons as possible, no matter how popular because that is how they get an increase of new subscribers. They also focus less on IPs and world building because they don’t need to convert their content into plush-doll merchandise and theme park attractions. Therefore, these are most likely the future studios that independent productions and auteurs will have to support their creative goals. And although their artistic products will be schelved alongside cheap online goods (Amazon) or (ab)used by algorithms to find the “perfect match” per consumer (Netflix), at least they won’t have to direct a previssed, producer-lead, blue/green-screen superhero movie that uses the director purely as a publicity tool rather than for their creative talents.