First with some news:

Pixar will release Luca, their second film exclusively distributed via Disney +, in a couple of months, which annoyed some Pixar employees. Although the issue appears to be harmless, it follows a long history of Pixar playing Disney’s (disrespected) junior: in the 1990s Disney threatened to make terrible straight-to-video sequels of Toy Story unless Pixar made it, Pixar’s braintrust was instrumental in reviving Disney Animation after Disney acquired Pixar in 2006, etc. Pixar has essentially been the linchpin of Disney’s hold (monopoly?) on “family-friendly entertainment” through their animated features. And now it’s simply a sign of disrespect to Pixar’s worth and even for the theaters, the latter needing Pixar films for their highly profitably family theater-outings. When the live-action Mulan was released last year on Disney +, they did so initially with a hefty add-on price that valued the film above all other releases on the platform. But Pixar receives none of that treatment.

Rotten Tomatoes took away Citizen Kane’s perfect 100% rating after it found an old, not-so-hot review by the editors of the Chicago Tribune. This is quite a bizarre trolling done by RT, considering the review doesn’t really in my (humble of course) opinion classify it as rotten, it’s just that the writer was unsure at the time if it was the greatest film of all time. In the end it doesn’t really matter at all for any reason, but isn’t it strange that Paddington 2 now holds that 100% fresh honor and not the greatest film of all time?

Former actor Rudy Giuliani, known primarily for his legendary performance in F. W. Murnau’s 1922 german expressionist film Nosferatu, won the Razzie award for worst supporting actor in his surprise cameo in last year’s Borat Subsequent Moviefilm. Congrats, it was well deserved!

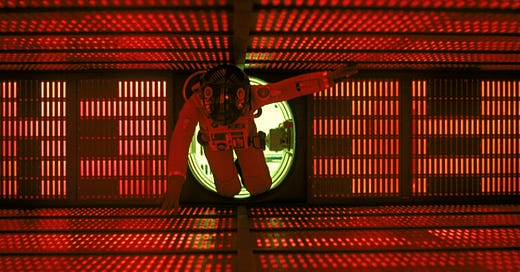

Retro-Review: 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, US/UK, 1968)

Because of the timespan in which 2001: A Space Odyssey covers (from our bestial beginning to our space-travelling future), the film takes a broadly relevant position on what it means to be human; as all good science-fiction should do. That’s why the iconic match-cut between the bone and the spaceship is so popular: it’s the time in which we figured out how to evolve into what we are today and what implications that may have for our future.

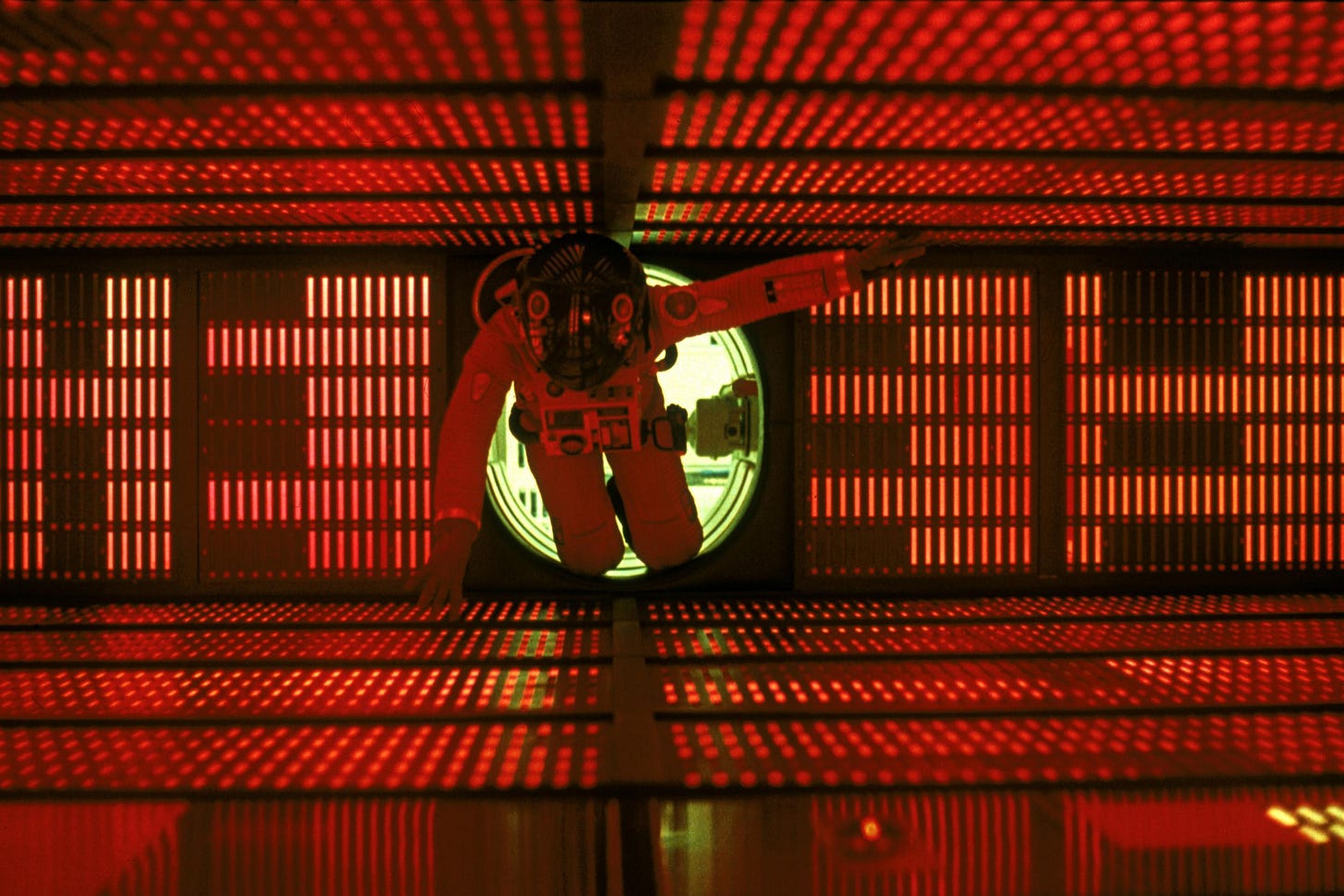

It’s remarkably one of the first films in which artificial intelligence was seriously examined. And rather than just being a side character made of tin like Robby the Robot in Forbidden Planet, the HAL 9000 artificial intelligence, or just Hal, in 2001 is given an anthropomorphic treatment like with Data in Star Trek: The Next Generation (watch season 2, episode 9: “The Measure of a Man”). In the plot of 2001, Hal fails to trust that the two humans that are managing the mostly automated spaceship will be able to accomplish the mission. That completed mission is what Hal is programmed to accomplish at all costs without regard to human life, the latter becoming more of a liability that ought to be excised. And so that’s what Hal tries to do, which works for one of the crew members but not the second. This reveals the obvious paradox of how artificial intelligence can easily escape our (human) grasp. But the film also reveals where this disregard for life in favor of progress initially came from, which was in our very long, unending history of tribal fighting. For much of our ancestral history, the act of killing was made central to our understanding of the world and to each other. Therefore when a machine was programmed that took our ancestral baggage and mixed it with 100% goal-oriented efficiency, humans were seen as a hindrance, just like the hominids in the first sequence (“The Dawn of Man”) trying to drink some nasty puddle water. And this problem of artificial intelligence still has not been properly articulated 53 years later.

The film itself works in a mostly audiovisual sans dialogue way. For the two hours forty minute runtime, only forty minutes contains dialogue. This is a large departure from Kubrick’s previous films, especially Lolita and Dr. Strangelove, which both rely on their dialogue as the main attraction. By forgoing dialogue, 2001 works on a more subliminal level, one unaware of the surface-level, cultural norms that are expressed through language. I’m not sure to what degree Kubrick was influenced by the French New Wave, but he displays a knowledge of the film as a visual medium much like Godard or Marker were using in their films earlier in the same decade. If talkies were the logical shift away from silent pictures in the late 1920s, then these films from the late 1950s to 1960s were then the logical rebound back to film as a primarily visual medium (Newton’s Third Law of Motion of course).

The final sequence in the room is always one of the first questions asked when two people talk about the film: what does it mean? I have my own theory…, are among the most popular lines of dialogue. I’ve never been particularly interested in this as much as the artificial intelligence or Dawn of Man sequence because it’s whole point was obviously supposed to be ambiguous. Also, Kubrick already answered this question in an interview from 1969, in which he was asked if he deliberately tried for ambiguity:

No, I didn't have to try for ambiguity; it was inevitable. And I think in a film like 2001, where each viewer brings his own emotions and perceptions to bear on the subject matter, a certain degree of ambiguity is valuable, because it allows the audience to "fill in" the visual experience themselves. In any case, once you're dealing on a nonverbal level, ambiguity is unavoidable. But it's the ambiguity of all art, of a fine piece of music or a painting -- you don't need written instructions by the composer or painter accompanying such works to "explain" them. "Explaining" them contributes nothing but a superficial "cultural" value which has no value except for critics and teachers who have to earn a living. Reactions to art are always different because they are always deeply personal.

And aside from the theorizing and ambiguity, I think this final sequence is simply the visual sequel of the bone to spaceship match-cut already mentioned. The reborn star-baby that descends back to Earth is the evolutionary equivalent of the humans able to travel to the moon by spaceship relative to the Dawn of Man hominids. Whereas the first evolutionary step was told elliptically through the match-cut (which is basically implying: you know this story, no need to repeat it here), the second was a timeless trip through ageing and rebirth, which is functioning on a theological, spiritual level that is unique depending on whatever “superficial cultural value” one brings to the film. Take from that what you will.

There is obviously so much more to say about the film, which might come in a future stand-alone article. Needless to say, the film has aged quite well and still remains relevant in many ways.

Americans (and maybe also Canadians) can stream 2001 on HBO Max.

Article: How to read a movie by Roger Ebert

As most know, Roger Ebert is the most notorious American film critic of all time and influenced the writing form immeasurably. His greatest ability was in watching a film, being able to soak up all the things that made it work or not, why it was or wasn’t important, and condense all that into a newspaper column and then later onto his blog. And even if his review counters my own thoughts/opinions, there’s always a level at which I know he’s still right and honest.

All his reviews have been catalogued and are easily accessible via his website, RogerEbert.com, which is now run by his wife and features criticisms and reviews by many online film critics. I came across Ebert’s method of dissecting a film frame by frame, which he did at film festivals and schools, when I was in film school and since been fascinated by the idea. In this short article he explains the basics of this method of watching a film, or as he calls it, How to read a movie.

I think this is a simple yet effective method of really looking at a film’s composition and how that may affect the viewer. And the best part, there’s no need being a film expert or having visual training in any form for this. One need not even pause the film every frame to notice what the composition might be doing. For instance, Ebert outlines his basic findings from his frame by frame analysis in a single paragraph:

In simplistic terms: Right is more positive, left more negative. Movement to the right seems more favorable; to the left, less so. The future seems to live on the right, the past on the left. The top is dominant over the bottom. The foreground is stronger than the background. Symmetrical compositions seem at rest. Diagonals in a composition seem to "move" in the direction of the sharpest angle they form, even though of course they may not move at all. Therefore, a composition could lead us into a background that becomes dominant over a foreground. Tilt shots of course put everything on a diagonal, implying the world is out of balance. I have the impression that more tilts are down to the right than to the left, perhaps suggesting the characters are sliding perilously into their futures. Left tilts to me suggest helplessness, sadness, resignation. Few tilts feel positive. Movement is dominant over things that are still. A POV above a character's eyeline reduces him; below the eyeline, enhances him. Extreme high angle shots make characters into pawns; low angles make them into gods. Brighter areas tend to be dominant over darker areas, but far from always: Within the context, you can seek the "dominant contrast," which is the area we are drawn toward. Sometimes it will be darker, further back, lower, and so on. It can be as effective to go against intrinsic weightings as to follow them.

Give it a try on a film you usually watch over and over because I’m sure you’ll find interesting compositions that explain who the character is or what they’re doing from just that single frame. Or better yet, finding something hidden in the composition might make you appreciate the film even more that before.