Weekly Reel, October 27

IATSE Agreement, Halyna Hutchins, Foreign Film Oscar Contentions, Alien Retro-Review, and The French Dispatch.

(Note: To make sure these posts always lands in your inbox, drag this email from the Promotions tab into your Primary tab and select “Yes” when you’re asked if you want future messages to land in the same place. Thanks!)

News:

The IATSE and big film studios reached a tentative agreement to avoid a strike that would shut down film production in the US. The agreement includes a 10-hour turnaround time between shifts, 54-hour weekend turnaround, yearly 3% wage increases, increased meal penalties (fees for working through lunch), and a living wage for the lowest workers. The 60,000 members still need to vote to ratify the agreement, but some argue that it doesn’t go far enough: most workers already have the 10-hour turnaround, the 54-hour weekend turnaround has too many loopholes, the more expensive productions can easily pay the meal penalty fees, and the proposed wage increases are lower than the inflation rate. Given the current climate of labor relations, covid-era film production limitations, and massive interest among IATSE members to strike, they could vote against the agreement, potentially still strike, and hope for better results.

Alec Baldwin accidentally killed cinematographer Halyna Hutchins and seriously injured director Joel Souza on the set of a western film. It’s unclear exactly what will happen because of the ongoing investigation, but once more information is released, I’ll write up a long post to examine why/how something like this could happen.

Early Oscar contentions so far for the foreign film category include Worst Person in the World (Norway), Flee (Denmark), Paolo Sorrentino’s Hand of God (Italy), Unclenching the Fists (Russia), Noomi Rapace’s Lamb (Iceland), Compartment No. 6 (Finland), Palme d’Or winner Titane (France), Great Freedom (Austria), Post Mortem (Hungary), A Hero (Iran), Escape From Mogadishu (South Korea). The other countries are still narrowing their lists.

Retro-Review: Alien (1979, Ridley Scott, UK/USA)

For my science-fiction film class at university, we watched James Cameron’s Aliens instead of the original (sans “s”) by Ridley Scott. That was our week of studying body horror, of Julia Kristeva’s Abjection, which is the horrifying subjective experience of individuating the self from other. Aliens does a fine job playing with these themes wrapped in the signature Cameron-effects-suspense trifecta. But it’s from Ridley Scott’s Alien in which the audience truly experiences the abject through body penetration and phallic alien imagery run amok on screen.

20th Century Fox wanted to produce more science-fiction films after the success of Star Wars, so they greenlit this aliens-in-space project. The producers brought in young director Ridley Scott after David Giler and Walter Hill revised Dan O'Bannon’s script, which Scott recognized would play better as a horror film. On the scale between Star Wars and 2001: A Space Odyssey, the resulting picture Scott created falls in the Eraserhead sub-zone leaning towards 2001. Like 2001, Alien’s greatest moments come from its stillness, silence, and suspense, which mixed in with the alien’s fixation on entering and exiting the human body creates an unsettling feeling closer to sickness than shock.

The film opens with an emergency message that wakes up the long-sleeping crew to a distress signal coming from an unexplored planet. When they reach it, they explore the surface until finding a large structure that appears fossilized yet inorganic. One of the crew members descends into one of the ‘you-obviously-shouldn’t-be-going-into’ kind of rooms in which he finds a giant bed of eggs. Out of curiosity, he examines an egg up close, which hatches and a small alien baby thing launches and sticks to his face. Against protocol and common sense, the crew takes his now unconscious body with the alien mask on board their ship to try and save him. They don’t. The alien leaves his face and the guy recovers. But while they’re eating dinner before going back into their long sleep, the guy convulses and one of cinema’s greatest moments occurs when a small alien violently shoots out of his stomach and runs across the table.

For the rest of the film, each of the crew members produce different tactics to get rid of the alien to no avail. They all die one-by-one while the alien grows into slightly larger than human shape. It’s only Ripley, played brilliantly by Sigourney Weaver, who makes the escape and finally gets rid of the alien by shooting it out of the ship after buckling up to the seat in a space suit. This is vaguely how I remember the Aliens plot as well.

Alien received mixed reviews from critics when it was released, possibly for its queasy body horror, but also because of its novelty in the genre. Over time the cinephiles, science-fiction fans, and film industry would remember the film as one of the best science-fictions films ever made. It importantly pioneered and remains the best in the now bloated science-fiction ‘crew dying on a spaceship one-by-one until the final person is standing’ sub-genre. An ensemble 2001, if you will.

Unlike Star Wars and other 70s science-fiction films that feel camp today, Alien retains its special and visual effects edge even with its 42-year-old puppets/props. Due credit goes to Swiss artist H. R. Giger for designing the alien, Michael Seymour’s production design, concept art from Ron Cobb and Chris Foss, and Derek Vanlint’s masterful low-light camera work. As with most films made before the streaming era, this film would benefit from the pitch-black room, roaring speakers, inability to pause, giant screen of a theatrical viewing.

Alien can be found (don’t regard the last sentence) streaming in 4k on Disney + because of Disney’s acquisition of 21st Century Fox, a family friendly movie for all this Halloween season!

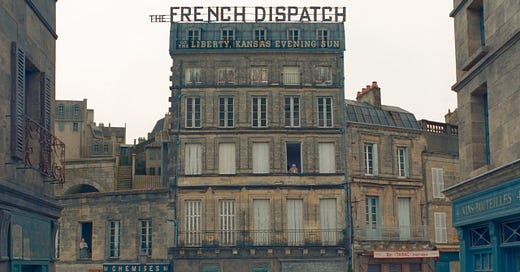

Review: The French Dispatch (2021, Wes Anderson, USA)

Wes Anderson’s new film, The French Dispatch, was released last week after being delayed over a year, much to the relief of my favorite cinema in Munich, which can now take down the original Spring 2020 promotional posters. In its first weekend’s release at the US/Canada box office, it made $1.5 million at 52 theaters, which doesn’t sound like much compared but set the pandemic record for most ticket sales per theater at $25,000 and most for any independent film.

The French Dispatch tells the story of a foreign correspondence publication in the French town of Ennui-sur-Blasé for its Kansas readership. The plot follows the dramatization of four articles by four different journalists in the final issue of the publication following the death of the founder/editor (who in his will demanded the publication shut down at once upon his death). In the first short section, Herbsaint Sazerac (Owen Wilson) narrates a travelogue of the city for us to become acquainted with the town. Along the way we see nice neighborhood split images between its past and present and whimsical moments of Wilson biking through carefully constructed city artifices.

Next is a biographical article by J.K.L. Berensen (Tilda Swinton) about a mentally disturbed painter (Benicio Del Toro) in prison for double homicide and his complicated relations with both his muse/prison guard (Léa Seydoux) and art dealer (Adrien Brody). My favorite of the episodes, it reveals the sexual/artistic/political dimensions relevant throughout the entire film. It is Seydoux that dominates the relationship with Del Toro and Brody that commands Del Toro’s artistic reputation. Without either, he would just be another mentally disturbed inmate.

Then comes a “political/poetic” story about a young revolutionary couple (Timothée Chalamet and Lyna Khoudri) by the journalist Lucinda Krementz (Frances McDormand). McDormand gets an inside scoop on the student demonstration (literally inside a bed with Chalamet), even editing the manifesto of the young revolutionaries. Besides from revealing obvious unethical journalistic practices, which McDormand easily performs as banal, the story runs more as a fairy tale but not to the point of complete facetiousness.

And finally comes the most personal of the bunch, which is an interview/profile by Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright) on the accomplished chef to a police commissioner that quickly turns into a hostage rescue mission. Emphasizing his black, gay, American outsider status, Wright plays the role less whimsical and more sincere while recounting the story verbatim during a live talk show. Not wanting to give too much away, there is a great animated car chase scene in the climax that further lifts the overall cinematic craftsmanship.

As is obvious to some, the film is a love letter to The New Yorker and its various authors over the years. For instance, the editor of The French Dispatch, Arthur Howitzer Jr. (Bill Murray), is based on the legendary co-founder and editor-in-chief of The New Yorker, Harold Ross. Sazerac is Joseph Mitchell, Wright is a combination of James Baldwin and A. J. Liebling, and the political-poetic story is based on Mavis Gallant’s two-issue coverage of May 68 in Paris.

The most striking aspects of the film are typical of Anderson’s filmmaking in general, which is the amount of physical, artistic craft that goes into every single detail of the frame. Doing so creates an impressionistic mise-en-scène in which we can see it obviously isn’t realistic, but it doesn’t matter. It achieves a unity of pictorial vision that suspends disbelief in the direction of artifice that makes it possible to tell tongue-in-cheek jokes humorously, as in the case where the student protestors are playing chess against the police as the two sides are separated by a barricade. The same moment wouldn’t easily hold in another film that doesn’t employ this artifice because of Anderson’s unique ability in crafting a world within films that anyone interested in film can immediately identify. His style further lends itself to the dramatization of journalistic pieces from a publication known for its wit, artistic characterizations, and celebrity authors.

Regarding the name of the fictional French town, Ennui-sur-Blasé, which translates to Boredom-on-Blasé in English, reveals a more interesting thematic connection in its figurative translation. Ennui is a type of feeling that arose in the 19th century among the French youth, one that can especially be read in the poetry of Charles Baudelaire, which became associated with disappointment, emptiness, and alienation in the modern world. In this way it becomes something closer to angst than boredom. Blasé on the other hand refers to an indifference towards something banal.

The conjunction of the words therefore means something like angst/alienation-on-indifference, which in a way describes the episodic sub-structure of the film (four parts with themes that we’ve all seen before) providing the basis for the main characters of the pieces on top (filled with tension and trying to find their subjectivity told through modernist-era journalists). But what makes this interesting is that the Ennui-sur-Blasé stories are sent to Liberty, Kansas. The telling of the stories is itself what liberates the so-called boredom. I wrote a similar argument for the confirmation between spectator-story in Fellini’s 8½.

The cast of the film makes it so that an Oscar winner/nominee is rarely absent from the frame. We see again the repeat Wes Anderson cast of Brody, Swinton, McDormand, Wilson, Seydoux, Murray, etc. with the key additions of Del Toro and Chalamet, and Wright. If you’re interested in a humorous, easy to watch film that is original and not a big-budget sequel or adaptation, then The French Dispatch deserves your time and ticket sale.

The French Dispatch is playing at a theater near you (or maybe to that small indie theater you need to drive a long way to).

No essay review/commentary this week as I’ve been busy looking into the Halyna Hutchins shooting.

Thank you for once again checking out my Substack. Please like it and use the share button to share it. And don’t forget to subscribe to it.