Weekly Reel, September 29

Disney theatrical releases, IATSE strike authorization vote, Afghan New Wave?, Paisan review, Mission: Impossible Retro-Review, and mid-budget films essay.

Some (belated) news:

Disney is going to release the rest of their big releases with a 45-day theatrical window. During the lockdowns they were releasing these titles on the Disney + app for $30 and/or concurrently with the theatrical release, which hurt at the box office. But once cinemas opened, Disney was encouraged after the solid theatrical releases in the summer. This 45-day window is good for theaters and cinema in general but bad for Disney +. It comes a couple of months after Scarlett Johansson sued Disney and Christopher Nolan left Warner Bros. for Universal because of the problems with the straight-to-streaming options, which bypasses the cinematic experience.

As covered before on the Weekly Reel, the AMPTP (the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers) had until September 20 to make modifications or respond to the requests of the new contract with the IATSE (International Association of Theatrical Stage Employees). Because the AMPTP failed to respond whatsoever, the IATSE will hold a strike authorization vote October 1 to determine if there will be a nationwide strike of camera operators, cinematographers, editors, etc. If a strike occurs, all film and television production in the United States would have to completely stop because the technicians won’t be able work and the big studios can’t hire non-union employees. The contract that the big studios are failing to adopt calls for modest caps on workday hours (production days often last 12 hours or more), improved working conditions, and increased medical coverage.

Afghan filmmaker Shahrbanoo Sadat speaking at the San Sebastian film festival addressed the misconceptions about Afghans in the films made in or about Afghanistan from the last 20 years. She laments the lack of original production and propaganda, because “NGOs, flush with funding, encouraged films about the resurgence of women’s rights, elections and other themes that put the new administration in a good light.” Sadat thinks this era created “very bad films, full of clichés and stereotypes and, tragically, were deemed as points of reference about Afghanistan by both the local and international community.” Nonetheless, she is hopeful that there will be a new wave of Afghan filmmakers currently exiled in Europe, like herself after her escape from Afghanistan in August, who will bring a fresh perspective to her home country beyond what is said about Afghanistan in Western headlines.

Paisà (1946, Roberto Rossellini, Italy)

Paisà, or in the English-speaking world, Paisan, is the second film in Rossellini’s War trilogy following Rome, Open City (1945), which was the film I reviewed in the first Weekly Reel. Like with the first film, Rossellini used war-destroyed, major Italian cities as the setting for Paisà, this time using six locations across Italy instead of just Rome. At each location, a short film plays out for 20 minutes, each unconnected to the previous. In doing so, it broadened the ability of Rossellini and his six writers (including the co-writers from Open City, Amidei and Fellini, and also Klaus Mann, son of Thomas Mann) to explore what the war meant for various groups of people across the country: as Rossellini explained, each episode is connected through the themes of communication, corruption (“the tragedy of poverty and hunger that leads to deception that is itself corruption”), and love.

The six episodes of Paisà follow a linear temporal and geographic logic; in Rossellini’s words: “It follows the route of the Allies who landed in Sicily and gradually made their way up the peninsula to the north.” But as Italian film critic Adriano Aprà explained, there also exists a linear linguistic and ideological logic in how the characters understand each other. In the first episode, a young Sicilian woman wants to go to her family in a nearby town but is being used by the American army in order to guide them to a different location. In the end, the woman is falsely blamed for killing an American soldier when it was actually a German, which the Americans see as a betrayal, thereby creating a barrier between both the language and the American commitment towards the non-fascist Italians.

Each episode then gradually progresses, mostly with American troops understanding an Italian’s problems/language, until the final episode in which secret service Allies and Italian partisans are executed together after being caught by the Germans. According to Aprà, Paisà shows that it takes effort (and sometimes violent struggle) to understand each other, but once achieved makes it possible that “different cultures can meet and rise up together.” In this way it’s clear to see where the title comes from: “The story of Paisan is the story of how the foreigner, the other, can become one’s fellow townsman or villager.”

In order, the episodes take place in Sicily, Naples, Rome, Florence, the Emilian Apennines, and the Po delta. In the three urban centers that episodes two, three, and four use, the cities appear as rubble wastelands, which reaches its peak in Florence. In that episode, a British woman and Italian man are trying to make it through the city center in which active fighting is still taking place between Italian partisans and Germans. Because it was shot on location in Florence immediately after the war, the major sites were still in ruins, which was used in the story to create a sense of confusion as the two desperate civilians are guided through the city. Like with Open City, Paisà depicts the landscape itself as one of the neorealist film characters along with non-actors and documentary footage to create events that are “neither completely fictional nor absolutely true, but they’re probable.”

The expansion across the country for the film was made possible through the production funds of Italian producer Mario Conti and American producer, Rod E. Geiger; the latter using the profits from Open City’s successful overseas distribution. This Italian-American cooperation on both the producer and writer levels helped create the Italian-American balance evident within the film. Even though Paisà premiered at the first postwar Venice Film Festival in 1946, Italian critics were skeptical of the film. It wasn’t until the French critics (proven throughout time to be the best critics of film) described the film as a masterpiece several months later in which it received its wide international distribution and continuing critical success to this day.

Paisà can be found on the Criterion Channel and also for sale at Criterion along with the other Rossellini war trilogy films.

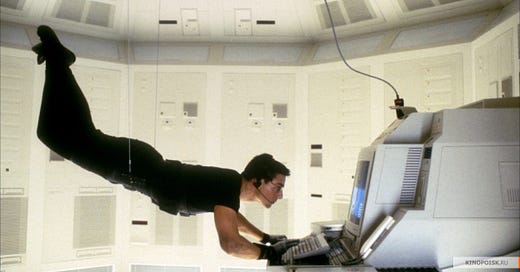

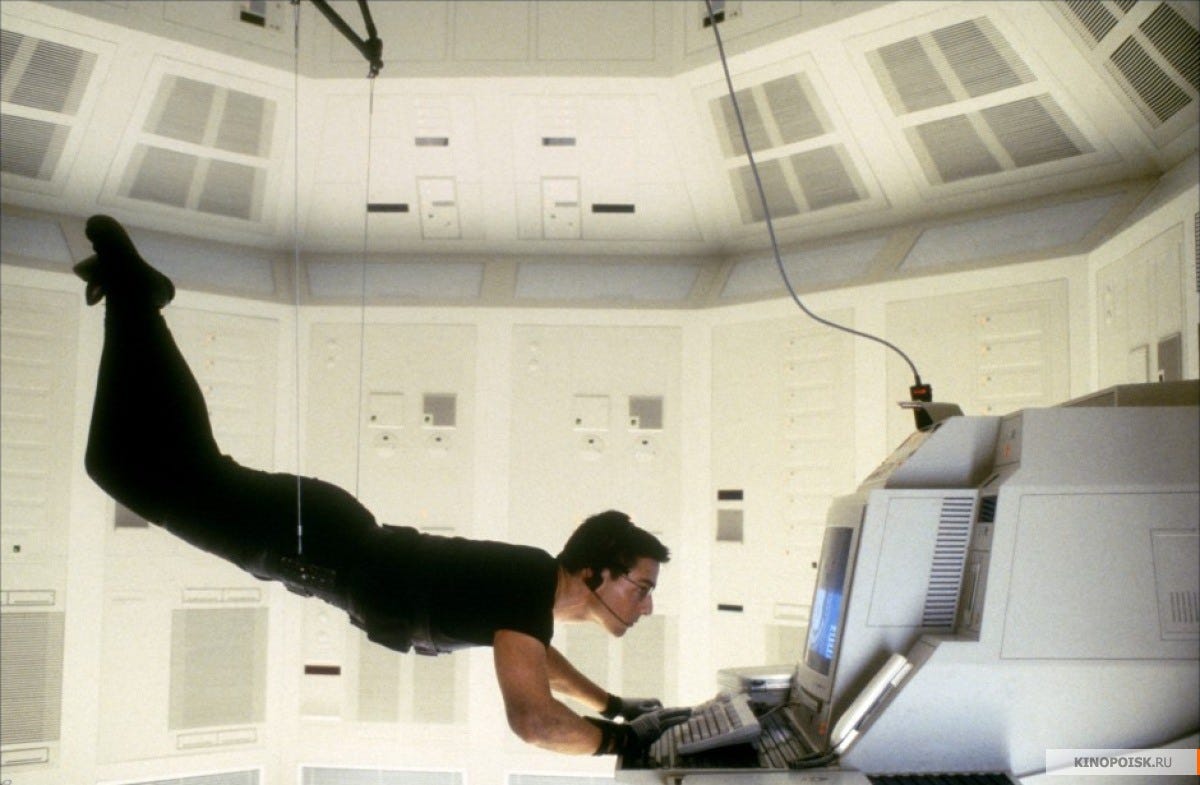

Retro-Review: Mission: Impossible (1996, Brian De Palma, United States)

The only Mission: Impossible films I’ve seen are the first and sixth (Mission: Impossible – Fallout); the latter was during the Golden Era of MoviePass, which was a short-lived service that let one see any film in the theaters for $15-20 per month. As is obvious from that description, it quickly ran out of cash and doesn’t exist now (the big theater chains in the US now run services similar to it because of its effectiveness with subscription-based services even though they consistently complained about it). But when it was working, I saw everything the theaters had to offer, even the sixth Mission: Impossible installment while having no context of the previous four films, which I still enjoyed.

Before rewatching the first Mission: Impossible recently, I barely remember the first time I had watched it but was interested in seeing 1) how it aged and 2) how it compares with the other two Brian De Palma films I’ve seen in the last couple of months (Blow Out and Body Double).

After a rough transition to Hollywood in the 1970s (though still releasing solid hits like Carrie and The Fury), De Palma found his breakthrough in the 1980s with Dressed to Kill, Blow Out, Scarface, Body Double, and The Untouchables. After a large slump with The Bonfire of the Vanities in 1990 and couple more well-received films, he made Mission: Impossible in 1996, which ended up being his highest grossing film of all time but marked the beginning of the end for his critically well-received films.

Mission: Impossible began as a TV series from the late 1960s to early 1970s that featured a small team of secret agents taking down typical Cold War enemies. Tom Cruise liked the series as a child and decided it would make a good inaugural film for his new production company, so he hired Sydney Pollack to work on the story until hiring De Palma after meeting him at a dinner with Steven Spielberg. The resulting film was a major financial success and solidified Cruise’s reputation as a big action movie star that performs his own stunts.

(Fun story: during the film’s overseas promotion, the CDU in Germany called for a boycott because Cruise is a Scientologist and in Bavaria the CSU was trying to ban scientologists from joining the civil service because they claimed Scientology acted like a mafia, which of course threatened their own mafia-like control of Bavaria. The Church of Scientology claimed the CDU/CSU was flirting with religious discrimination similar to the Nazi era and had one of their biggest members, John Travolta, meet with President Clinton.)

In terms of the plot/story, Mission: Impossible doesn’t make or need to make sense because, as Roger Ebert wrote in his review, De Palma is concerned with style rather than story; and that “this is a movie that exists in the instant, and we must exist in the instant to enjoy it. Any troubling questions from earlier in the film must be firmly repressed.” And regarding the style, the thriller/action moments can still suspend the audience in disbelief even with the now gimmicky spy-genre tropes because of De Palma’s experience making neo-Hitchcockian films from the previous decade. The part that has the most difficult time holding up today is the roof of the train climax in which a helicopter is flying through a tunnel following a super high-speed train, which to our cgi-trained 2021 eyes looks obviously fake. But until reaching this moment, the realism is taken for granted.

The film franchise in 25 years has made over $3.5 billion from six films with two more scheduled to release. In addition to that, the critical ratings keep rising with each release, which is rare for a film franchise but especially for one in which the only cast/crew continuity between all the films are actors Cruise and Ving Rhames. Mission: Impossible still holds up surprisingly well and makes for a quick watch whether one is catching it on TV or watching it on Netflix with one’s friends.

Essay: Why Theaters Still Need the Mid-Budget Movie by Douglas Laman

One of the reasons you aren’t finding anything on Netflix compared to half a decade ago is because of the rise of streaming services from individual studios that are taking back their original licenses sold to Netflix in the 2010s. Because of this, Netflix (and Amazon to a lesser extent) required massive amounts of content in a short period of time. Therefore, they began filming their own content, which began with series but later started luring in big actors, writers, and directors for feature films. But because Netflix is an online streaming service and doesn’t exhibit theatrically, they fund mostly low- to mid-budget films that don’t require massive box office returns.

The reason they were able to make these mid-budget films from famous filmmakers (Mank, Da 5 Bloods, I’m Thinking of Ending Things, etc.) was because the big studios left that gap open. Fincher, Lee, and Kaufman, who traditionally went through studios or studio subsidiaries to distribute their films found less opportunities in the late 2000s and 2010s as the mid-budget specialty studios began closing down or reducing their output. This happened with Touchstone Pictures and Miramax, both owned by Disney, which released more mature, mid-budget content in the 1990s to 2000s but were defunct by the 2010s. This happened at each of the big studios during this decade, which happened to coincide with the rise of Netflix.

The trend of studios favoring tentpole productions over mid-budget theatrical releases reached its climax in the summer of 2019, the last time normal theatrical viewing was possible. Since then, studios have had to slow down their tentpole theatrical releases, which allowed the recent mid-budget releases of Old and The Green Knight to compete in theaters without much competition. Writing for Collider, Douglas Laman noticed that

the success of these two movies serves as the most recent reminder that the theatrical exhibition space is not just a domain for big-budget blockbusters. It can also be home to more challenging fare aimed at older moviegoers. The success of these two titles also reaffirms something that’s been true for years now: studios need to return to regularly making mid-budget movies. The bread-and-butter of outfits like Warner Bros. and Paramount Pictures have largely migrated over to the various streaming services but the likes of Old and The Green Knight demonstrate that there’s still plenty of financial viability in bringing these projects to the silver screen.

Of course, major studios have done themselves no favors in terms of not only being largely unwilling to make these kinds of films but also being largely uninterested in the ones they do produce. Throughout the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the first films theatrical studios have sold off to streamers or dumped on premium-video-on-demand services have been comedies, courtroom dramas, and other genres exclusive to the world of mid-budget filmmaking.

But mostly because theaters have been closed. On streaming:

Interestingly, Netflix hasn’t been able to launch ongoing franchises by emulating big-screen blockbusters like Bright or 6 Underground, but they did score genuine pop culture phenomenons with low-key fare like To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before or The Kissing Booth. It wasn’t so long ago that Hollywood regularly produced movies like these for the big screen in the form of titles like 2014’s The Fault in Our Stars. But the scarcity of these films in the theatrical space created a void that streamers could move in and fill.

It isn’t just streamers that are helping to keep mid-budget movies off the big screen, though. Theatrical studios themselves bear the brunt of things by failing to greenlight these projects, crafting such an exclusionary future for big-screen cinema with a limited understanding of what a theatrical experience can accomplish on the part of movie studios.

Finding who to blame (streamers or studios) for not releasing mid-budget films theatrically is mostly a chicken and egg problem, I think.

In terms of what mid-budget films offer:

mid-budget films allow for a wider range of experiences to get explored. With lower financial risks compared to the budget of The Suicide Squad or Jungle Cruise, studios, in theory, can use midbudget features to explore provocative and challenging material. A great modern example is the $20 million budgeted Hustlers, a box office hit that centered its narrative on sex workers. The very fact that the film focused on sex workers, let alone depicted them in a compassionate light, would’ve been impossible to pull off in the domain of a big-budget movie.

And finally, regarding the financial implications:

On top of everything else, producing mid-budget films ensures that the domestic marketplace isn’t only reliant on a handful of blockbusters to keep box office momentum going. That may seem like a good idea when something like Avengers: Endgame is raking in the dough but not all big-budget titles become automatic successes. You need mid-budget films to compensate, or even serve as a replacement, for the severe box office bombs like King Arthur: Legend of the Sword and Dark Phoenix. The past is full of examples that prove that relying just on big-budget fare to carry the day doesn’t work 100% of the time. Producing mid-budget films creates a necessary balance in this marketplace.

This is especially true in this time where tentpole films are failing to reach their $1 billion at the box office while still remaining extremely expensive to finance. Expect in the coming months more interesting mid-budget theatrical options: The French Dispatch, Last Night in Soho, and Licorice Pizza.

Thank you for checking out my Substack. Please share it if anything strikes you and please don’t forget to subscribe.