What Are the Americans Up To? (Berlinale Dispatch)

Perhaps the biggest festival to not have American films as their centerpiece, the Berlinale premieres mostly independent, non-commercial world cinema.

The Berlinale takes place during an interesting time of the year regarding American films. January and February are theatrical dumping grounds for non-awards contenders, the Oscars are in March, and the Sundance Film Festival was less than a month ago. The Summer blockbuster season doesn’t begin until May and it’s far too early to roll out an Awardsy theatrical release starting in the Fall. Therefore, it’s a near-guarantee that the big American studio releases and/or films they will spend tens of millions of USD to promote for the awards season won’t premiere here. Cannes and Venice will receive those films simply because of their prestige and dates, May and August. So what are the Americans up to at Berlinale?

This festival, which, as I’ve covered, is a self-styled political film festival in favor of world cinema about challenging subjects, is premiering several American films for their international release (as opposed to an initial “world premiere”) after having been released at Sundance. This includes Loves Lies Bleeding, A Different Man, Sasquatch Sunset, Between the Temples, and I Saw the TV Glow. But there are others getting their world premiere here at Berlinale: Spaceman, Through the Graves the Wind is Blowing, Treasure, and Cuckoo. (It should be noted that an “American” film is a more slippery category. There are co-productions with other countries, which are how the majority of American films are released here, as well as American actors leading films made/set in Europe and non-Americans making films in the USA. This also doesn’t include other North/South American films, which is relatively sparse this year.)

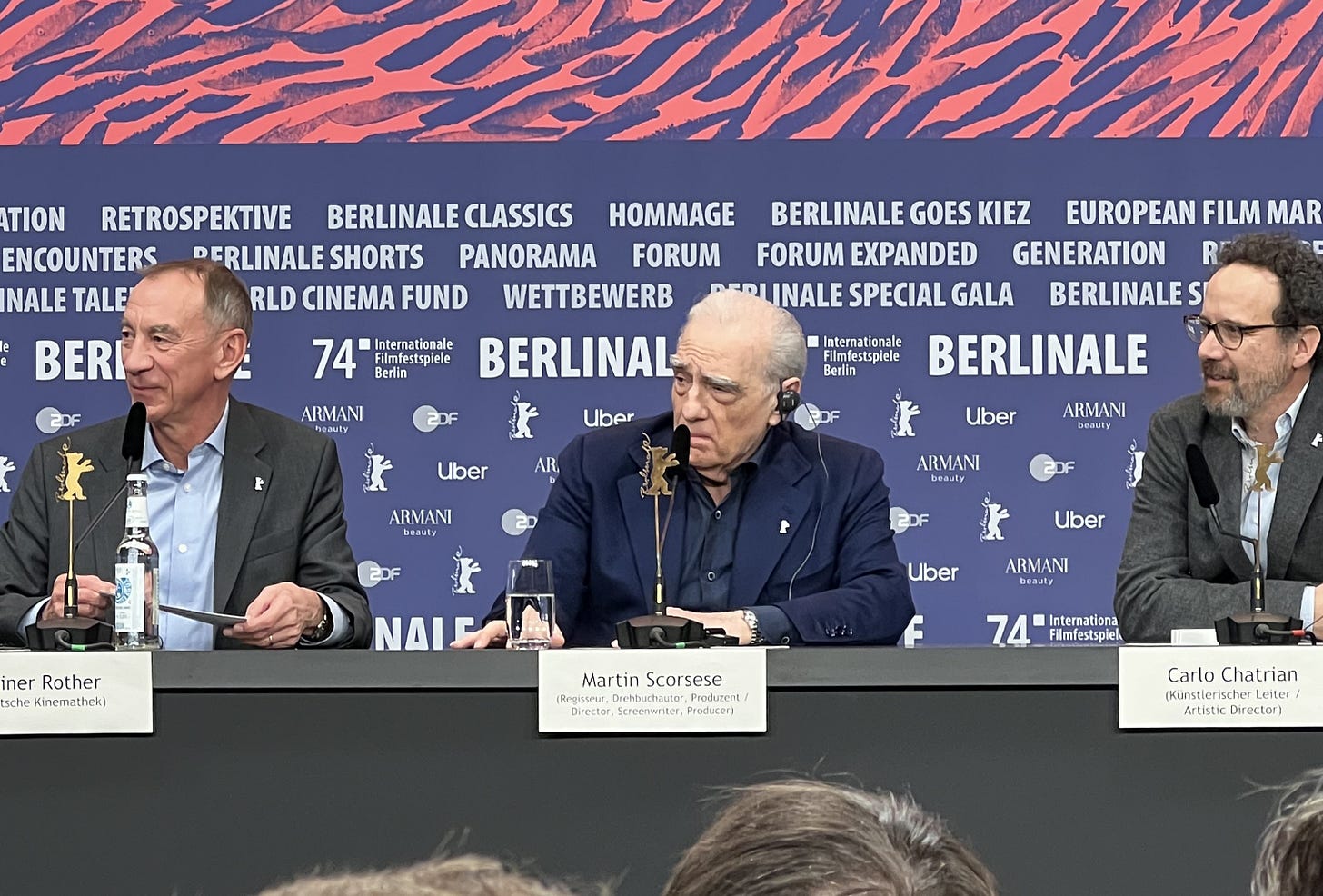

Martin Scorsese IRL

The two most anticipated Americans at this festival are Martin Scorsese and Kristen Stewart. Scorsese, who’s attended various Berlinales since opening the 1981 edition with Raging Bull, is receiving the Honorary Golden Bear lifetime achievement award followed by screenings of The Departed, a brand new 4k restoration of After Hours, and the premiere of Made in England, a documentary about the working relationship of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, which Scorsese narrates. Stewart is returning this year in the film Love Lies Bleeding (out of competition) after having served as the jury president last year.

Although Stewart commands attention in a room of journalists, Scorsese created traffic chaos into the press conference, where if you didn’t line up ninety minutes before it started you weren’t getting a seat. Asked about his thoughts regarding the role of a film festival, Scorsese thinks they’re important for audiences to hear a new voice and artist that has the potential to change how one thinks about life, providing a new point of view. “We’re all here, let’s communicate through art.” As is typical, Scorsese provided mini film history lessons after most questions. He watched films, foreign dubbed, on B&W TV when he was a child; lasagna was his favorite dish from his mother; the most recent films to inspire him off the top of his head are Past Lives and Perfect Days.

His two more poignant points came from questions about the relevance of criticism today and whether cinema is dying. Scorsese argues that critics are important in their ability (and perhaps necessity) to curate ideas and filmmakers for younger people. With the massive options available due to streaming, it’s extremely relevant for critics to push and focus younger people in certain directions. And with the introduction of streaming, he sees that as a transforming rather than killing cinema, which will always exist in a collectively physical theatrical form. The individual voice is the only thing that can be held onto, which provides us important historical and cultural lessons. He tells us not to let technology scare us; we need to be against being consumed and tossed away.

Kristen Stewart and ‘Love Lies Bleeding’

Asked about her opinion on the Berlinale, Stewart likes its inherent radical leaning and willingness to examine non-commercial films with statements that ruffle some feathers; simply: “it’s cool here.” Stewart commands the press conference better than most, who gives interesting, insightful, and funny answers that shows she can hold court with apparent ease. No doubt she feels promoting a film has less stress involved than being jury president, which she called an “incredible, surreal, and absurd” experience. Though she loves the festival, it was very scary to represent a jury, especially in front of the press. Overall, she used the experience of watching and talking about films with the other jury members as a consolidated film school that taught her a lot.

Regarding the film she was here to promote with director Rose Glass, Love Lies Bleeding, she likes that she’s able to bring this story, made by an Englishwoman in New Mexico about the dressing down of some very American iconographies, to Berlinale and feel the friction. Having been a massive fan of Glass’s last film, Saint Maud, Stewart agreed to work with her before reading the script. Glass’s pitch was the story about a powerful woman, literally, a female bodybuilder (played by an extremely committed Katy O'Brian) who Stewart’s character quickly falls in love with. The story is imbued with extreme roid-rage and a nineteen-eighties film photography where both male leads (Ed Harris and Dave Franco) have various size mullets. For Stewart this was the opportunity to make something “so fucking cool.” It’s ability to switch between violence and romance and drama never feels strained, much like a Coen brothers macabre comedy.

The Berlinale premiere happened days after a long and “uncensored” Rolling Stone article, where, like in the film, Stewart queers the standard hetero-setup with images of traditionally masculine activities (bodybuilding, combat sports, etc.). Stewart was happy with how the article turned out as well as the attention it was getting—conservatives had a predictable kanipshin—but doesn’t understand why there aren’t more images of empowered women like this. It’s their time.

‘A Different Man’

The only American film premiering in Competition is A Different Man, written and directed by Aaron Schimberg, starring Sebastian “post-Winter Soldier” Stan, Renate Reinsve (breakout star of The Worst Person in the World), and Adam Pearson (his second film with Schimberg after his debut in Under the Skin). It features Stan as Edward, an aspiring actor with neurofibromatosis who falls in love with his neighbor, Ingrid (Reinsve). He’s crippled with social anxiety, thinking his features are the problem. He undergoes an experimental treatment to get rid of his neurofibromatosis, which works so well that he turns into Sebastian Stan. With this new freedom, he disavows his previous life by moving away and changing names. But, since this is a drama, complications arise when he finds out that his problems are deeper below the surface than previously thought after he meets the exuberantly charismatic Brit, Oswald (Pearson).

Defending cinema at the press conference, Pearson argued that “good movies change how you think about the world for a day; great movies change how you think about the world for a lifetime.” (You can guess which one he thinks this film is.) Schimberg, who’s cleft palate provided him insights into how and why one should change physical “abnormalities,” defended his decision to feature neurofibromatosis so prominently because he wanted to create a deeply personal film rather than participate in the discourse on exploitation; “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” is his position on its representation. Pearson dropped another pull quote about the ordeal: “everyone’s messed up, let’s be messed up together.” (Reinsve got away without answering any questions, a welcome pleasure for many at the press conference.)

(This post is becoming a bit long, but I would be remiss to not include the Sachs/Hittman discussion.)

Ira Sachs and Eliza Hittman On Actors

One of the few non-screening, non-presser events I attended was the Berlinale Talents ‘I Hear You: For a Language of Trust on Set’ discussion between Ira Sachs and Eliza Hittman. I took damn near verbatim notes on what they talked about but will only include the greatest hits here. In about eighty minutes (Sachs left ten minutes early), the two NY indy filmmakers provided a master class in how to direct actors, especially on a smaller budget, which anyone aspiring to do so should watch, and also showed clips from Passages, Never Rarely Sometimes Always, Little Men, and Keep the Lights On.

(On finding emotional authenticity) Sachs: get out of the way as much as possible, don’t allow intrusions into how the actors interact with the fictionalized world they constructed, act like it’s a therapy session where he attends to the actors discovery, it’s his job “not being the third in the room.”

(On casting) Sachs: doesn’t do rehearsals or script readings before shooting; he doesn’t want certain ideas to set before the camera rolls. Hittman: her characters are rooted to some part of her, therefore wants the cast or crew member to also be able to find themselves in the story.

(On bonding with actors) Hittman: depends entirely on who the actors are, will find commonalities as a starting point; for Never Rarely Sometimes Always, she had the two lead girls write down very personal things about their lives then share them with each other while she was away. Sachs: similarly, for Passages, he met Whishaw and Rogowski at a Parisian café and left them to get to know each other after five minutes.

(On the camera) Hittman: uses 16mm because it captures skin tones and the face with more authenticity, which fits her intimate close-up shooting style; also long-takes have a certain risk and therefore greater meaning with a finite film reel.

(On keeping actors safe) Hittman: a film set is like a construction site that needs to turn into a church, to make magic and emotional truth out of a bunch of technical equipment.

(On the hardest time of the day) Sachs: the beginning when you have to tell everyone where to go and what to do. Hittman: it’s all terrifying.

(On intimacy coordinators) Sachs: doesn’t use one, it would break the connection between the actors, but understands their value. Hittman: hasn’t used one but is important for navigating consent with the inherently lopsided power positions on set.

(On being a female director) Hittman: has battled a lot of sexism and misogyny in her career; whenever she’s stressed out or other complications arise, she can always say “clear the set” and give herself some space to work things out. A a kind of magical ability.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t already done so to read more on the Berlinale.