Wilde Times

Oscar: A Life worth remembering and body of work worth reading; from Socialism to Sodomy Laws and everything in between.

ONE CAN easily imagine Oscar Wilde lounging on a Victorian chaise the afternoon after a long evening thinking up the line, “only dull people are brilliant at breakfast.” When he’s having a light literary feud with another member of the London elite, he might come up with, “always forgive your enemies; nothing annoys them so much.” Or when he’s backed into a corner during a legal dispute that will land him in jail, he’d say, “a good friend will always stab you in the front.”

Wilde’s witticisms come as either epigrams (play on words) or aphorisms (epigrams with a point or moral). They generally subvert clichéd epigrams, like getting stabbed in the back. He couldn’t even resist, on his deathbed, cranking one out against the ghastly hotel aesthetics: “This wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. Either it goes or I do.” He went soon after; the hotel (L'Hôtel) is still there, but I’m sure the wallpaper is now gone as well. Many of these statements can be found on small pillars next to the Oscar Wilde monument at Merrion Square Park in Dublin, across the street from the Wilde family’s main Dublin residence.

Making these remarks, or developing ideas based off them, are used by (perhaps too) many today in the irony-laden deportment of extremely online people. The reason Wilde was able to make these mordant and funny witticisms, as was Gore Vidal able to do as well, according to Christopher Hitchens, was because “he was, deep down and on the surface, un homme sérieux.” There was a sincerity in Wilde’s remarks that resonated with people over time, one that was rare to find in the Victorian era’s Puritan society of London’s elite—height of the Empire where the blood never dries yet still concerned what others did in the bedroom.

Wilde was truly—or has this cliché been thoroughly destroyed—born in the wrong place at the right time, or rather, chose to reside in the wrong place at the wrong time. As a proclaimed leader in the late-Aesthete movement and sometimes Irish/Socialist advocate, neither movements coalesced in London the final quarter of the nineteenth century. One can see him thriving as a pre-Raphaelite contemporary or sipping beers in Dublin pubs with Yeats and Joyce, but he was both too young and too old for that. He neither lived outside of the second half of the nineteenth century nor outlived Queen Victoria. And while Wilde admired Victoria and wrote poems about her, the Victorian era of London despised him, celebrating his imprisonment and early death.

Oscar Wilde was born in Dublin in 1954; his mother was a tall Irish nationalist writer and advocate, and his father (average height) was an eye doctor and prominent science-writer. Therefore, Wilde was born into a high-society/elite-salon household that hosted all of Dublin’s famous writers and scientists and various other elites passing through from the United States, UK, and Europe. At these intellectual gatherings, Oscar and his brother Willie ran around and provided a youthful energy to the drab Great Famine environment. Oscar, an early momma’s boy, first became interested in Greek literature and culture. Because of his family’s connections, he attended the Eton-of-Ireland, Portora Royal School, then went to Trinity College to pursue Greek studies before applying for a scholarship to Magdalen College, Oxford, which he easily acquired through academic excellence. Now an Oxonian, Wilde wrote poetry, which he wanted to do after graduating, but gravitated mostly towards drama. He was also more of a raucous nuisance on campus, who more than once was chewed out for running amok of rules & regulations.

The path to playwright wasn’t straight or obvious. After graduating in 1878, he moved south to London to pursue high-society connections that would land him in the company of the nation’s great writers, politicians, and other figures of supposed polite society. While he was able to put together a small collection of poems for publication in 1881, it sold less than a thousand copies and reviews emphasized the overbearing effect of influences—he had yet to find his voice. In 1882 Wilde went on a long, financially lucrative speaking tour in North America, where he traveled throughout North America perfecting his oratorial skills through essays on aesthetics and art. (He kissed an elder Walt Whitman after visiting him in New Jersey.)

After returning, he decided marriage was the next step. All the while Wilde had been writing plays and pitching them to British and American actors he thought would fit the roles. He supported himself, and his new family—two sons born 1885-1885—through an extensive amount of book reviews for “The Pall Mall Gazette” and other publications. And because of his now solid reputation as a dandy and leader in the post-pre-Raphaelite Aesthetic movement in London, Wilde became editor of “Woman’s World” magazine. His reputation was heightened through the many social gatherings he attended and dazzled guests at, using those same epigrams and decadent observations of art that we know and utilize today.

By the mid eighteen-eighties, Wilde was well known in London society circles for his in-person debates and advancement of all things Aesthetic. For many women at the time, Wilde was an influential figure in interior decorating and clothing design, arguing for well-built pieces that eschewed fashion trends in favor of style. Regarding Art, Wilde’s main influences were John Ruskin and Walter Pater. As critics and essayists, Wilde adopted and expanded their positions on Art existing by itself, outside of morality and expounding on the sensual experiences that could be found in Keats or Swinburne and, in particular, Art’s relationship to Nature and Society. Wilde embraced Ruskin’s analyses of gothic art (by way of the pre-Raphaelites) and other art criticism, while nearly copy/pasting Pater’s Aestheticism, which Wilde came to embody in the public eye during this time. For a person who had only published a set of poems, Wilde received outsized attention for his largely unpublished opinions and arguments on Art.

Wilde held firm in his belief that art was separate from morality. Asked whether his early poems were “impure and immoral,” he responded:

A poem is well written or badly written. In art there should be no reference to a standard of good or evil. The presence of such a reference implies incompleteness of vision. The Greeks understood this principle, and with perfect serenity enjoyed works of art which, I suppose, some of my critics would never allow their families to look at. The enjoyment of poetry does not come from the subject, but from the language and rhythm. It must be loved for its own sake, and not criticized by a standard of morality.

Unfortunately, Wilde was living in a time/place where morality was inherent to Art, which was used against him in court before a swift riposte.

Wilde’s big break came in 1886 from his discovery, through meeting Robert Ross, of same-sex relations. Ross, a student at Oxford, successfully seduced the thirty-two year-old Wilde. Wilde’s justification came in two forms, intellectual and aesthetic, as is usual for him; first was the Greek love the Dorians perfected and spread, which Wilde learned in his early studies but was condemned by the socio-cultural landscape from trying/spreading. Second was his repulsion to domesticated home life and the physical nature of pregnancy, which was repulsive according to Wilde’s aesthetic judgements. As would later be revealed, Wilde learned through these affairs that the genius older man paired with a youthful, energetic lad perfected a kind of intellectual connection and inspiration that Wilde was missing, and which necessitated the improvement of his own artistic output. Indeed, after these affairs picked up in the last years of the eighteen-eighties, a flurry of writings and publications finally developed his long-awaited career as a writer/public intellectual.

Reviewed:

Oscar: A Life by Matthew Sturgis

Head of Zeus/Apollo, 740 pp., 4 Oct. 2018

Plays, Prose Writings and Poems by Oscar Wilde

Everyman's Library, 728 pp. 1 Jan. 2010

STILL INTERESTED in finding the right producers and actors for his plays, he was able to publish a collection of children’s stories in 1888 (The Happy Prince and Other Stories) and 1891 (A House of Pomegranates). Also, in 1891 he published a collection of comic-mysteries (Lord Arthur Savile's Crime and Other Stories) and rounded up previously published essays for a fully printed collection (Intentions). While this roundup doesn’t do justice to the amount of action in Wilde’s life in these few years, Matthew Sturgis’s masterful biography, Oscar: A Life, explores every nook and cranny through exhaustive amounts of detail that never fails to entertain, even when recounting the many characters, famous, infamous, and unfamous, who interacted with him. While the previous big-bio Pulitzer-winner of Wilde from Richard Ellman delved into speculation and literary theory, Sturgis takes a straight-line approach through exacting life-details.

The essays of Intentions reveal the intellectual baggage Wilde was carrying from salon to salon. “The Decay of Lying” is, as are the others in this collection, a Socratic dialogue that defends the unreality of Art, that the lying involved with fiction is what gives it power and meaning. Art should be about lying, not Realism based on Life or Nature. And, an interesting aphorism, that Life imitates Art more than Art imitates Life; bad Art is subsequently that which copies Life or Nature. (Wilde, for instance, wasn’t the biggest fan of Henry James.) While he obviously wasn’t speaking directly about autofiction, one (I) can make the connection, nonetheless.

Wilde’s essays in general, in today’s world, have so many outdated or archaic references that it’s a wonder how they’re able to remain relevant. He’ll travel effortlessly between Browning and Meredith to Phædrus and Eros, sprinkle in Latin and Greek, and conclude with a dozen extended aphorisms on Art in dialogue form. This juxtaposition between timeless maxims and dated references makes casual reading through them a form of Rosetta Stone reverse engineering into the intellectual ideas and time that Wilde & Co. were living.

But the two best of Wilde’s 1891 publications were his novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, and political essay, The Soul of Man under Socialism. For different reasons, among different groups, these would help solidify Wilde’s legacy before his death at decade’s end. To start with the shorter of the two, Wilde became increasingly interested in both Socialism and Home Rule politics in the back half of the eighteen-eighties. He read the literature, signed the letters/petitions, and conversed with the leading figures in London, which increased the ire of many ‘looking for an excuse’ with the Aesthete dandy. According to Sturgis, Wilde wrote the essay during three consecutive mornings for a friend’s political paper, which allowed him to finally expound, pen to paper, paper to print, his long-sought-out-for political philosophy. As anyone could have guessed, it was heavily based on aesthetics but is still regarded as one of the most well-written essays on Socialism.

In short, Wilde advocated a kind of Socialism towards Individualism via anarchism. Socialism would allow individuals to work for themselves instead of others. Altruism’s remedies are perpetuating the problem. Caring for the needy, while important in other ways, doesn’t solve their plight. Authoritarian Socialism won’t do, people should do as they please. Voluntary association is much better than compulsion. Private property crushes individualism: it makes people want to have rather than want to be: growth > gain. This leads towards his main two points: Jesus was the ultimate form of anarchic individualism against altruism and that Art is the only form of Individualism available to mankind. At the same time, on continental Europe, the Second International was founded a couple years before, which had banned anarchists due to Marxist pressure. Their main dispute was between Libertarian versus Authoritarian Socialism, which produced a clear winner in 1917.

On the fiction-front, Dorian Gray’s publication and first-run sellout launched Wilde into his coveted published-author position, from which he would launch his playwriting career. (An analysis of the novel is moot considering its reputation and prevalence, there’s nothing new I could add, except that it would be worthwhile to revisit the Preface, which was added to later printings and is basically just a greatest-hits of Wilde’s witticisms. My favorite: “It is the spectator, and not life, that art really mirrors.”) Camille Paglia wrote in Sexual Personae that Wilde is the synthesis of French and English Decadent Late Romanticism joined with English comedy. He was an Apollonian conceptualizer (like Botticelli, Spenser, Blake—the GOAT, and Rossetti) and cold Late Romantic elitist, which are terms of endearment from Paglia. She argues that Dorian Gray reveals the erotic principle (person into objet d’art) and decadent art in general (daemonization of the Apollonian; which can be found in Bret Easton Ellis’s work today). If Wilde was apprehensive at the beginning of his affairs in 1886, by 1891 he was printing for all to read his position on Dorian-based love, that “love that dare not speak its name.”

THE HIGHS and lows of 1891 for Wilde were tremendous. In one year, he had published two collections of stories, a collection of essays, a novel, and a political essay. Not bad. These were the highs. The low, singular, was meeting Lord Alfred Douglas, the love and eventual destroyer of his life. Every genius comes with its own parasite. LAD was the Dorian Gray to Wilde’s Basil Hallward/ Lord Wotton, but instead it was Wilde’s bright future trapped in that painting while reality was an ignoble play. LAD’s father, the Marquess of Queensberry, a comical Victorian villain and abusive figure, was brutish in all aspects of his life, which grew to near-homicidal heights after finding out that his young, already-corrupted son was being corrupted by Wilde. Wilde and LAD were quite infatuated. Their relationship went far beyond the usual homosexual patterns Wilde enjoyed with other long-term companions.

By this time, it was apparent Wilde was more at-home in Paris than London. Wilde was speaking accentless French and could stage plays there that were illegal in the UK, like Salomé, because it depicts Biblical figures. Young French writers were enraptured by Wilde’s wit and stories, none more than André Gide, who melted to the floor when Wilde spoke. (While in Paris in 1891, Wilde also met twenty-two year old Marcel Proust and had dinner with his parents. Unfortunately, the two never met again.) France, compared to London, was fixated less on class and sexual prohibitions via morality, which Wilde argued existed separate from Art and made it a more natural place to reside/publish. As an Irishman, Wilde felt thrust into English life. So why didn’t he leave for Paris, or Dublin, or even the United States? While Sturgis doesn’t argue one way or the other and make a judgement, it seems to be due to complacency. Wilde liked loafing about, enjoying the company of LAD and young male escorts and champagne dinners and expensive sets of perfumes.

With his newbuilt fame, Wilde started writing new plays. His previous period-piece dramas never sold, so he switched to contemporary dramas/comedies of high-society, the first of which was performed in 1892 as Lady Windermere’s Fan. (Wilde’s reputation among dandies and other Aesthetes at that time: he wore a green carnation at the play’s premiere, which started a green carnation trend in London.) The play performed well right away among both critics and audiences. For the first time in his life, Wilde had a steady income, which he used to afford a life of maximum leisure—carefree living of doing nothing all day—an expensive lifestyle. From this success, Wilde knew he wanted to keep writing drama, but more in terms of upper-class comedy/morality, and possibly in French. Wilde repeated the success of plays yearly with A Woman of No Importance and An Ideal Husband, which further exacerbated his decadent lifestyle and nights out with LAD and other lads.

What was happening at Wilde’s home? His wife, Constance, caring for the two boys, Cyril and Vyvyan—Vyvyan’s son, Merlin Holland, Oscar’s only grandchild, is a pre-eminent Oscar Wilde researcher today—didn’t receive much attention from either Wilde or Sturgis. Constance doesn’t receive much insight or analysis in direct proportion to how much Wilde did as well. She was supportive of Wilde, aware of his fame and influence, but most likely wasn’t privy to the same-sex disposition and rumors circulating London.

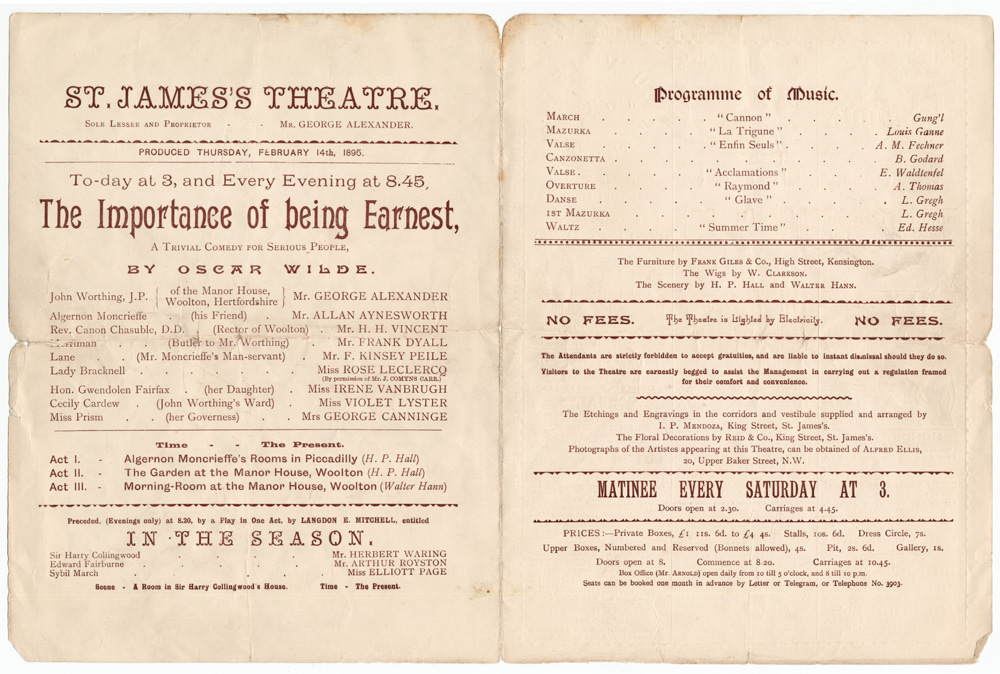

ANOTHER YEAR of highs and lows was 1895, which inversely tipped heavily towards the latter compared with 1891. The high was the premiere of The Importance of Being Earnest on Valentine’s Day. The lows began during that premiere: LAD’s father, who had been harassing his son and Wilde because of the constant rumor mill surrounding their sexual (recently made illegal) proclivities. The thuggish Marquess, who’s now known for Wilde’s downfall and establishing the modern rules of boxing, showed up to the St. James Theater in London with a box of vegetables. Having been tipped off to this scheme, Wilde ensured tight security for the Marquess, who wasn’t allowed anywhere near the theater’s innards. He left the veggie box in a huff.

Days later, the Marquess left his calling card out in public with Wilde’s name penciled in next to sodomite, a serious allegation in Victorian England. That was it for Wilde, who sued the Marquess for libel at LAD’s urging but against his lawyer’s opinion considering the public’s knowledge of Wilde’s indiscretions. Wilde fell into the spider trap: the Marquess had been gathering names, dates, witnesses, and locations through private investigators and a team of lawyers. Wilde’s plan was that it would be one man’s word against another, which isn’t enough for prosecution. Moreover, the young men who were witnesses were low-class, therefore disreputable compared to Wilde in court. Nonetheless, Wilde went ahead knowing that his social reputation would be squandered permanently. As the trial neared, it was apparent the Marquess knew what he was doing, which would likely trigger a reverse prosecution putting Wilde on the defensive with possible jail time. Wilde could’ve backed out, left for France, or any number of other options, but he pressed ahead because he didn’t want to incur the huge legal costs of the Marquess.

Wilde put on a show, but the jury acquitted the Marquess, whose information and witnesses led to an immediate trial against Wilde. Before his arrest, he was at home and could have fled. But he was steadfast in the resignment of his own catastrophe, against the wishes of his family. At the second trial, as second acts go, the reversal of fortunes against Wilde mounted. The men who Wilde had relations with, who broke the same law, were given money and immunity for their court appearances. The Marquess legal team was led by Edward Carson, an old Trinity College contemporary of Wilde, who easily defended the Marquess against libel and was now grinding down Wilde as prosecutor. (The Home Secretary at the time, H. H. Asquith, who handles law enforcement in England, was at a lunch with Wilde several months before. Because of Wilde’s jesting disposition, he made quips at the expense of Asquith, who was now enjoying this injustice. Asquith and Carson’s personal connections to Wilde shows how small London society was, which dealt mostly in petty disputes sometimes boiling over, as seen in this case.)

The first trial started less than a week after the St. James premiere of Being Earnest, which had stripped Wilde’s name off the bills and ads but gladly accepted box office receipts. Constance had taken the children away from London to escape the madness while Wilde stayed with his brother, his wife, and their mother. Wilde’s personal belongings at his residence were auctioned off to satisfy the many creditors who came to collect as much of the debt as possible.

Sturgis recounts the three trials in detail, remarking that Wilde looked “haggard and worn” after three weeks waiting for the second trial to begin. When Wilde took the witness stand, Carson pressed him on LAD’s poems about the

“Love that dare not speak its name”? – was it ‘unnatural love’?

Wilde replied:

“The ‘Love that dare not speak its name’ in this century is such a great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep, spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect. It dictates and pervades great works of art like those of Shakespeare and Michelangelo, and those two letters of mine, such as they are. It is in this century misunderstood, so much misunderstood that it may be described as the ‘Love that dare not speak its name,’ and on account of it I am placed where I am now. It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an elder and a younger man, when the elder man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so the world does not understand. The world mocks at it and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it.”

Wilde’s words created a sensation in court, and there was an outburst of clapping from the public gallery – mingled with some hisses.

He was ready for this attack because he’d been defending the separation of Art from morality for over a decade at this point, which was still relevant then and continues to remain relevant today.

As the second trial/act proceeded, to build suspense, the jury reached not guilty on two counts but no decision on the rest, requiring a third trial with new jurors. By the time this repeat trial was underway, Carson had thoroughly broken Wilde’s spirit and the ability of his defense to argue effectively against the solid evidence presented. Wilde was found guilty on seven misdemeanor counts and was given two years prison with hard labor, the harshest possible sentence.

While in prison, to prevent himself from losing his sanity, he began writing a wordy letter to LAD, essentially breaking off their relationship by showing how LAD’s sexual adventurism and mooching off Wilde’s fame and funds led to Wilde’s downfall. Only able to write a page per day and without being able to refer to the previous pages, its compilation and publication after Wilde’s death would be known as De Profundis, originally titled In Carcere et Vinculis. The letter was sent to Robert Ross to send to LAD, but Ross never sent it. But only months after leaving prison and going to France, Wilde and LAD reconnected, which risked the bankrupted Wilde losing his stipend from Constance, who forbade him from seeing LAD as the only condition. Apparently, Wilde just needed to get that letter out of his system. The two gallivanted around France, went down to Naples and other areas in southern Italy before separating one last time due to LAD’s hot-headed temper.

During his time with LAD, he wrote The Ballad of Reading Gaol, a long poem stretched to book length exploring prison life from a psychological and introspective angle. A relative rarity, it was an instant bestseller and the first few printings sold out. Other than the tepid print releases of An Ideal Husband in 1898 and Being Earnest in 1899, Reading Gaol, was his most successful release to date and was Wilde’s final publication during his lifetime.

Wilde’s health began declining rapidly in 1900, during which he developed meningitis from a previously untreated ear infection in prison. Robbie Ross, the young man who first introduced Wilde to same-sex relations over a decade before, was holding Wilde’s hand while the death rattle took hold. LAD, properly informed of Wilde’s impending death, had no plans of visiting. Wilde’s grave is now at the Père Lachaise Cemetery (established by Napoleon as a democratic gesture for all social classes to be dead together) in Paris, famous for Jim Morrison’s devotional mecca but also the resting place for Chopin, Piaf, Proust, Méliès, Stein, de Havilland, etc.

STURGIS’S BIOGRAPHY goes through Wilde’s life from beginning to end with exacting details to show the endlessly fascinating life and person who was Oscar Fingal O'Fflahertie Wills Wilde. Though dead at forty-six with a relatively sparse number of published writings (his complete works can fit into about 1,200 pages, shorter than War and Peace) compared to the size of his reputation, Wilde proves that quality over quantity matters more for one’s reputation. For instance, we could have had more than one masterpiece novel, another slew of gold standard plays, many more essays on aesthetics (this time dealing with the twentieth century), and a lengthy tome on Socialism and the rise of National Socialism.

Wilde would have been fifty-nine when WW1 started; he would have received the news the following year that his oldest son, Cyril, was killed in battle; he would have watched younger Irish authors like Yeats and Joyce rise to fame and make Dublin a more prominent city; he would have possibly been able to help shepherd Ulysses into print as an elder literary figure with the necessary connections in his late sixties; we could have heard his take on Modernism in literature at the end of his productive years; he could have watched feature films at cinemas. Wilde was officially pardoned in 2017 for his homosexual acts, but that doesn’t take away the amount of wisdom and art that Lord Alfred Douglas stole from us.

Wilde knew and played his role as court jester; those in power were prickled by this effeminate Aesthete and advocate of Socialism, who could easily out-talk anyone through wit and a cool demeanor. It wasn’t until the then recent enforcement of sodomy laws that these men could flex their resistance against Wilde in the form of an oafish classist like the Marquess. In an era where perfectly normal human impulses led him to be public enemy number one, he showed how resistance and being one’s own truth-filled Individual is the most important quality we have, aside from creating Art.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t already done so.