Weekly Reel, October 13

The Space Race, IATSE strike authorization, Johansson-Disney lawsuit, "In Cold Blood" book v. film, and Disney CEOs.

News:

The Russians will beat the Americans to space once again, this time in the production of a feature film. An actor, Yulia Peresild, and director, Klim Shipenko, will spend 12 days at the ISS working on the film along with the two cosmonauts on board. Tom Cruise and Elon Musk had planned to do the same last year, but once again the Russians put one over on the US in the (ongoing?) cultural cold war.

The IATSE voted to authorize a strike with a vote of 98% (a voting number only seen in third world dictatorship elections). This authorizes IATSE President Matthew Loeb to call a strike for “quality-of-life issues.” While the vote isn’t the direct vote for a strike, it sends the signals to the studios that if they don’t compromise, then all film production will shut down, which following the already limited amount of time to shoot because of Covid protocols is something that they can’t allow to happen.

Disney quickly settled the Scarlett Johansson lawsuit because of the bad press the former was receiving. The details won’t emerge anytime soon. The suit marked a turning point in contracts between the stars and studios in the dual theatrical-streaming release era, which shifted the emphasis away from box office receipts towards streaming numbers. It’s unclear whether other actors will follow Johansson’s suit, but since it’s Hollywood, we’ll have no idea what’s happening behind the scenes.

Retro-Review: In Cold Blood, Book v. Film

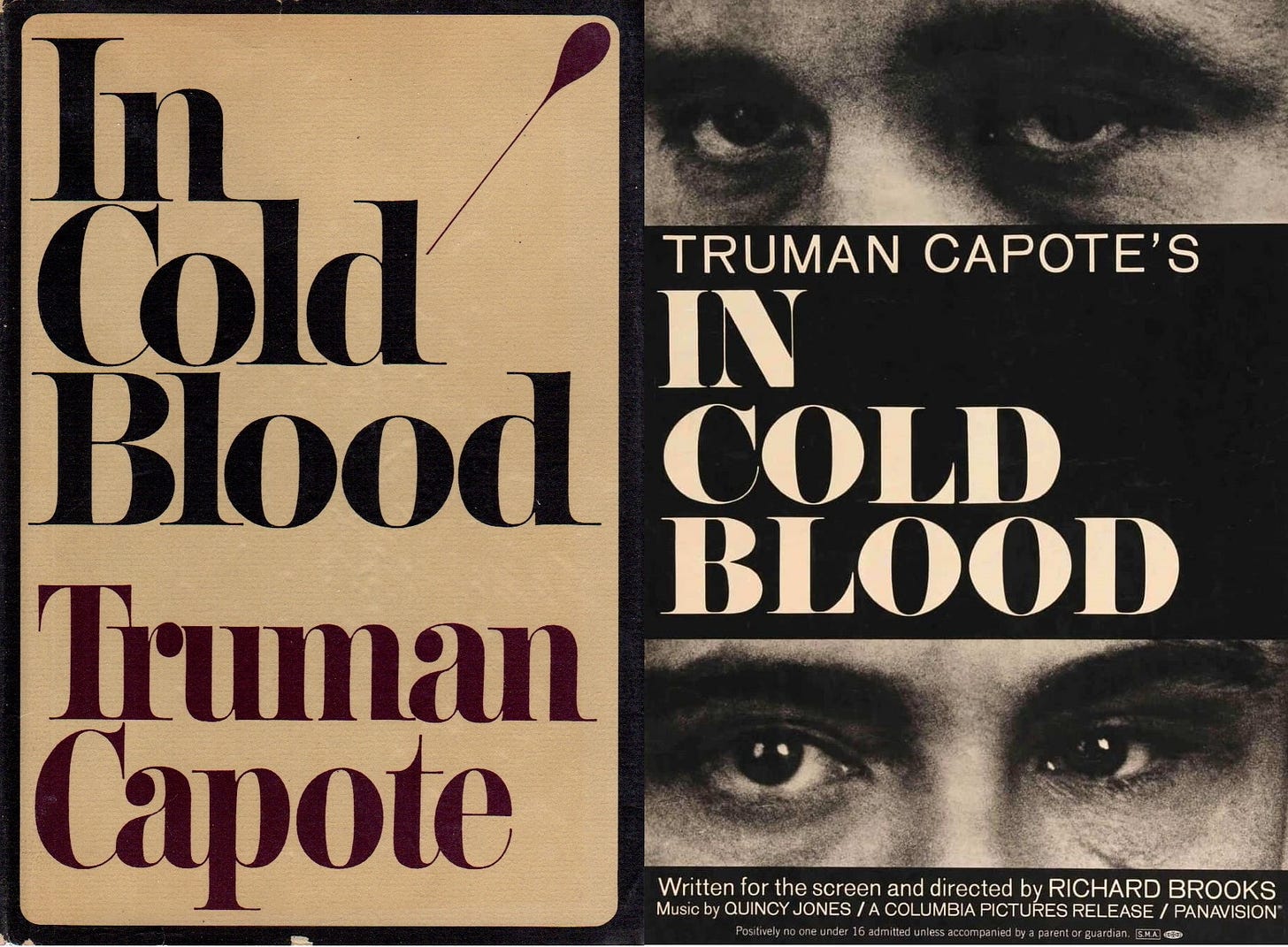

Similar to the Retro-Review back in April featuring a comparison between the American Psycho book and film, I decided to do the same after reading Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. The book was first serialized by The New Yorker in 1965 and published into a book the next year, which became so popular that they released a film adaptation the following year, in 1967. Today it’s regarded as a pioneer of the true crime genre, which I somewhat disagree with, and has sold the second most number of copies in the genre behind Vincent Bugliosi's Helter Skelter.

In Cold Blood tells the real story of the 1959 quadruple homicide of the Clutter family in Holcomb, Kansas. Two recently released convicts, Richard Hickock and Perry Smith, thought Herb Clutter kept a safe in his house with $10,000 inside. So they devised a plan to steal the money and leave no witnesses behind. And after getting to the house, they don’t find a safe but kill the family anyway. Then for the next two months they flee to Mexico, come back to the States, and are caught when the former prison roommate of Hickock told the detectives about the plan that Hickock had originally told him. Eventually they confess to the killings, stand trial for them, and spend a few years on death row before being executed by the state of Kansas in 1965, five months before the first installment of Capote’s book in The New Yorker.

Capote was prompted to write the story by a news editor, so he travelled to Kansas in order to spend years researching the killings through first-hand sources. For the first two months he was accompanied by his childhood friend, Harper Lee, who had just written To Kill a Mockingbird. They interviewed everyone from the town and those involved in the case, which amounted to 8,000 pages of notes and took six years until Capote had enough material to draft and serialize the book. After Hickock and Smith were caught, Capote had years to interview the pair while on death row, which gave him enough time to befriend them and learn the intricacies of their psychologies.

In the process of writing the book, Capote recalled that “choosing to write a true account of an actual murder case was altogether literary. The decision was based on a theory I've harbored since I first began to write professionally, which is well over 20 years ago. It seemed to me that journalism, reportage, could be forced to yield a serious new art form: the nonfiction novel.” And this is how the book unfolds, a mostly chronological re-telling of the events from the perspectives of the killers, the Clutters, the townspeople, and the detectives. In doing so, Capote excludes his own voice from the narrative, which created a story that reads like a novel with an omniscient narrator but is about nonfiction events. It’s also an early example of the New Journalism movement beginning at this time, which featured long-form journalism with a subjectivity and emphasis of the truth rather than the facts.

Even after 55 years, the book is compelling in its attention to detail, psychological accounts of the killers, and third act reveal of how the killing was done. What set it apart from any other genre was in its mixture between journalism, narration, and crime, which in turn helped inspire a newly emerging genre: true crime. But what sets it apart from much of the true crime today is the mystery of whether the suspect or suspects were the murderers, that important hesitation of guilt. In the book, we immediately know who the killers are. What makes it compelling is the literary cross-cutting it manages, which takes the reader from hunter to hunted wondering when the paths will cross and what will happen afterwards.

The two killers are rendered in great detail because of Capote’s years of interviews he conducted with the pair on death row. As can be detected in the book, Capote was fascinated with Smith’s sensitivity, which Robert Blake portrays nicely in the film. Blake and Scott Wilson (as Hickock) seem less intimate in the film than the book, in which a strange infatuation continuously arises in the latter, but in the film the physical portrayals allow one to see in detail the physical representations of the killer’s psychology (Smith’s leg, Hickock’s charming demeanor, etc.). To give the film as much realism as possible, most scenes were shot on location in Kansas. They even used the actual house and rooms in which the original Clutter family was murdered, which the viewer wouldn’t be able to know but provides the film a greater psychologically disturbing edge. 1967 was the first year of the New Hollywood movement, which featured films (Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, The Dirty Dozen, Valley of the Dolls, In the Heat of the Night, etc.) with more violence, nudity, language, and thanks to In Cold Blood, psychological disturbance due to the loosening of the self-censoring Production Code.

But as disturbing as the film is, it still feels slightly dated in its production and has a slower pace compared with the book. And in terms of genre uniqueness, the book helped begin and define both the nonfiction novel and true crime genres while the film remains firmly planted in the crime film genre. Nonetheless, I highly recommend both the book and the film, moreso the former, because of their psychological portrayals of the killers and what that killing meant to the town and public consciousness, and how the story unfolds, which is addictive and troubling.

In Cold Blood can be found streaming on the Criterion Channel.

Bob Iger’s Long Goodbye by Kim Masters

Bob Iger’s announcement of his intentions of stepping down as the CEO of Disney came as a surprise in February 2020 given his previous media announcement build-ups of the same announcement, but it looks like this time it was real. As you can tell from the date though, his announcement was soon followed up with his commitment to stay on as Disney Chairman to smooth out the transition during a turbulent time while Bob Chapek would gradually replace him as CEO. Chapek is a longtime Disney Parks by-the-numbers executive while Iger is the “big picture” visionary, meaning an outside the numbers, creative executive. So this is how they split up the leadership of Disney in the early announcements in the spring of 2020.

At the annual Disney summer retreat in Hawaii in June, Iger gave one final speech that tried to define what had made Disney, or rather his leadership over the last 15 years, special:

Iger decided to open the meeting by offering his parting advice. A longtime critic of over-reliance on market research rather than instinct and taste, he made an inspirational plea for the value of talent. He touched on the challenges of managing creators but stressed that every transaction at Disney — parks, consumer products, movies and television — starts with creativity.

“In a world and business that is awash with data, it is tempting to use data to answer all of our questions, including creative questions,” he said. “I urge all of you not to do that.” If Disney had relied too heavily on data, he noted, the company might never have made big, breakthrough movies like Black Panther, Coco and Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings.

Iger is right, you don’t need data, but he left out the part that you need to acquire both Pixar and Marvel.

Though a 28-year Disney veteran who most recently had overseen the theme parks and resorts, Chapek was an outsider in Hollywood. Known for cutting costs and raising prices, he was regarded by many with distrust if not outright hostility. So the version of the board retreat that made the rounds had Iger showing up Chapek, who was said to have followed Iger’s remarks by declaring in blunt terms that, in fact, Disney was now a data-driven company. It sent a chill through Hollywood.

Get ready for an even more formulaic Disney output.

Nonetheless, the retreat anecdote dovetailed with a narrative that was already taking hold among Iger confidants: that he had lost faith in Chapek and that his speech before the board was “a final warning” that Disney was veering off course. And the idea of the wrong man at the helm of Disney stokes a lot of anxiety in an industry that has seen Fox and MGM swallowed up, WarnerMedia battered by AT&T and Paramount transforming into a shadow of itself.

Now going back to before the retreat when Chapek first took over:

But even as Iger lingered, Chapek moved quickly to seize control, reorganizing the company in a way that diminished the power of some key Iger lieutenants as others have exited. “Every creative person is leaving or losing power,” laments one former high-level Disney exec.

The challenge confronting Chapek, and the leaders of every other legacy entertainment company, is daunting: They must serve Wall Street’s obsession with building their streaming services without alienating creatives, who still want a shot at the mind-bending paydays that come with success under a traditional model.

Iger always seemed reluctant to take the full dive into Disney +, which had come late and without a coherent strategy alongside Disney’s three, or four?, other streaming services. The best strategy for Disney + would be to put all Disney content on it, including non-Disney branded content, and completely avoid the theaters in order to maximize subscriber count. Although Disney in the 2010s cracked the code on billion dollar theatrical releases, it’s still a declining economy in terms of number of theatergoers. But with Iger out of the way, Chapek could be the one to take further steps into pushing for Disney + dominance.

But as important as the master of the Marvel universe is, he doesn’t direct or star in movies. Chapek still has to handle that part of the talent equation without the experience that Iger brought to the job. Many Disney veterans and outside observers think the public fight with Johansson never would have happened on Iger’s watch, and even before that blew up, the feeling among many in Hollywood was that Chapek was using the pandemic as an excuse to throw movies onto Disney+, steamrolling talent in the process.

Several Disney veterans believe Iger did not anticipate how aggressively Chapek would move to take charge. In The New York Times in April 2020, media columnist Ben Smith reported that Iger, mere weeks after Chapek became CEO, had “smoothly reasserted control” and “effectively returned to running the company.” Iger was said to have made his intentions clear to Chapek on a flight in March. In an email to the Times, Iger explained: “A crisis of this magnitude, and its impact on Disney, would necessarily result in my actively helping Bob [Chapek] and the company contend with it, particularly since I ran the company for 15 years!”

The funny thing about this is that Iger was brought in as CEO by the Disney Board of Directors after the group publicly ousted Iger’s predecessor for overstaying his welcome.

The critical question now is whether Chapek ever will be able to mimic the talent-friendly words that Iger said at the Aulani and convince anyone that he means them. “The single biggest topic is, does Disney now think its IP is more important than talent itself?” says Greenfield. “The question is, who is Bob Chapek?”

I think IP has always been Disney’s stronghold, from when they licensed Mickey Mouse watches up until they acquired Lucasfilm to get into the billion-dollar Star Wars merchandising business. The more accurate question is: does Disney now think its talent is important at all?

Thank you for checking out my Substack. Please share it if anything strikes you and please don’t forget to subscribe.