One of Us, We Accept You: ‘The Zone of Interest’ (Book & Film)

Martin Amis and Jonathan Glazer find news ways of depicting the undepictable, conjuring the incorrigible, and make us confront the horrors of being on the wrong side of a genocide.

For myself, honour is not a matter of life or death: it’s far more important than that. The Sonders, very obviously, hold otherwise. Honour gone; the animal or even mineral desire to persist. Being is a habit, a habit they can’t break. Ach, if they were real men – in their place I’d . . . But wait. You never are in anybody’s place. And it’s true what they say, here in the KL: No one knows themselves. Who are you? You don’t know. Then you come to the Zone of Interest, and it tells you who you are.

-Martin Amis, ‘The Zone of Interest’

"We accept her, one of us. We accept her, one of us. Gooble-gobble, gooble-gobble." This famous chant comes from the climax of Freaks (1932). The we is a carnival sideshow of ‘freaks’ (dwarf siblings, conjoined sisters, sacral agenesis, microcephaly, etc.) who initiate a trapeze artist into their group while she poisons her husband, for his inheritance, during their wedding reception. Hercules, the strongman conspiring with the bride, jokes about her becoming one of them, a seemingly ‘normal’ outsider. Their affair is found out, throwing the night in ruins and proving that she was the immoral freak. After its poor public reception at the beginning of the Production Code era, Freaks was rediscovered via the 1962 Venice Film Festival, eventually earning cult status for portraying a sympathetic attitude towards people with disabilities and the lower class (during the Depression), while raising questions of representation, point-of-view, who’s telling the story?

The incestual French teen siblings of Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers chant “we accept you, one of us! One of us!” when they accept a young American into their small bourgeois ménage-à-trois film club. Like Freaks, which they’re pastiching, The Dreamers turns its perspective-based story into a horror film regarding who one’s sympathizing with. Both stories end in rejection; one with the denial of fantasy-horror and the other with so-called ‘normalcy,’ showing how one can’t simply steal what they want from others without losing themselves in the process.

Is it a coincidence that The Zone of Interest, a story horrifically laden with questions of representation and point-of-view, used the One of Us visual effects company (found at the weacceptyou.com URL) to create an ambiance of smoke-ashy terror in 484 shots for the film? For sure. Nonetheless…

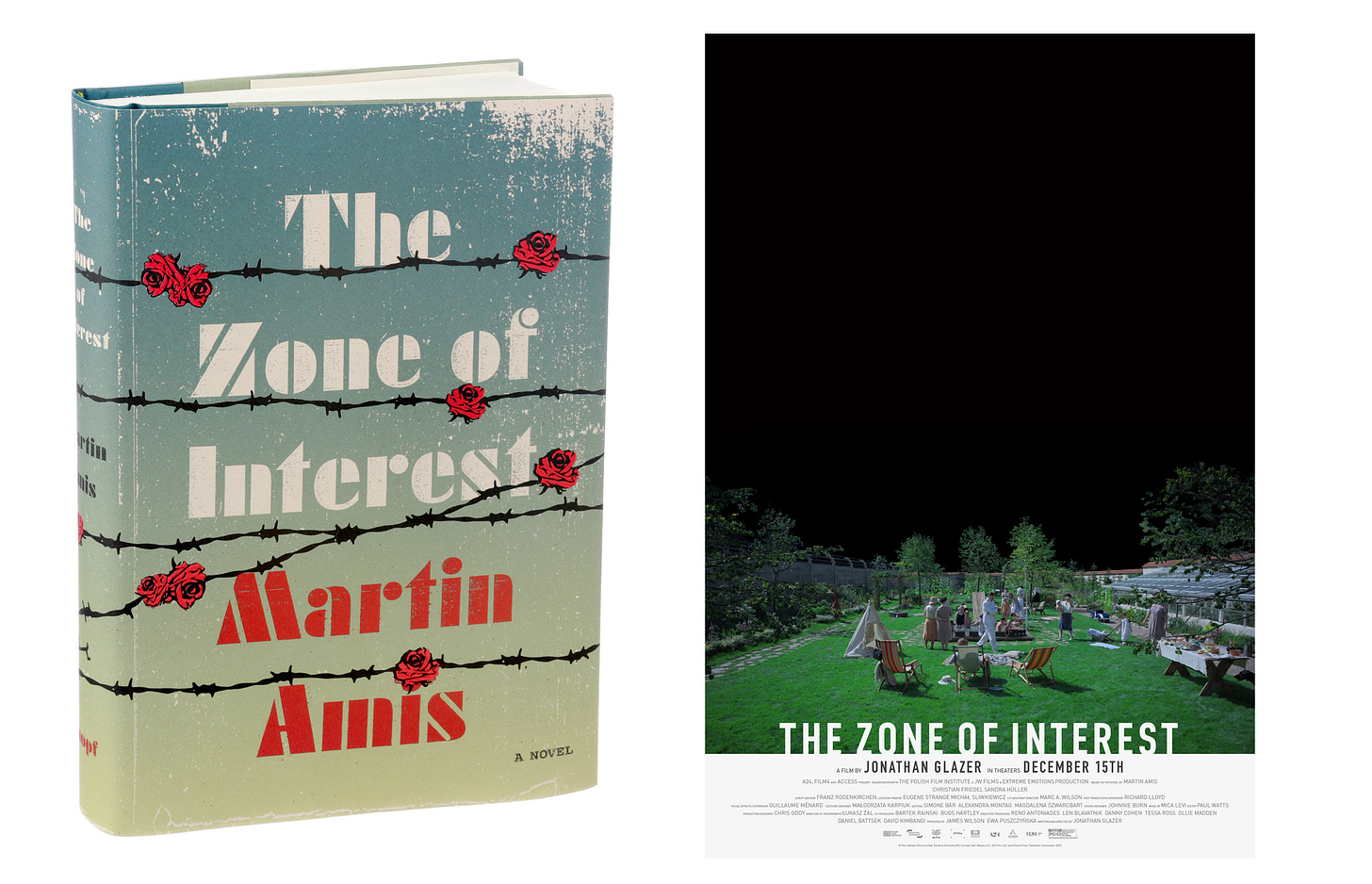

Martin Amis, author of The Zone of Interest—his penultimate novel—was born (August 1949) seven years after the events in the book and died on the same day (19 May 2023) its adaptation premiered at Cannes. The film, directed by Jonathan Glazer, is his first release since Under the Skin, exactly a decade before Zone premiered, and we’re now, in 2024, exactly a decade after the book was published. And for you history buffs, Freaks released theatrically the same month, July 1932, that the Nazi party ‘won’ a majority of seats in the Reichstag. A decade later, Rudolf Höss was commandant of Auschwitz, living with his wife, Hedwig, and five children on a small housing compound sharing a wall with the KZ, or death camp. In Amis’s heavily-researched story, Rudolf is renamed Paul Doll—Amis likes his playthings—and Hedwig is Hannah. Otherwise, the similarities between the film, which re-renames Paul and Hannah back into Rudolph and Hedwig Höss, and book is scarce. But those few instances are important, which I’ll point out throughout this essay.

The novel is neatly divided into six chapters, each featuring three character povs (Thomsen, Doll, and Szmul), an ‘Aftermath’, and an Acknowledgments and Epilogue: ‘That Which Happened’. Glazer does away with the character perspectives but includes his own after-the-war moment. Filmed on location in a replica house adjacent to Auschwitz, Rudolph (Christian Friedel), Hedwig (Sandra Hüller, the best actor of 2023), their children, their dog (played by Hüller’s irl dog), their housekeepers and servants, and the many camp officers roam around the Zone improvisationally while hidden cameras and mics, monitored by Glazer and cinematographer Łukasz Żal (Ida, I’m Thinking of Ending Things, Cold War) in the basement, capture their über lived-in performances. The medium and long shots create a coldly removed anti-perspective while the book relies on the characters’ internalization, creating a rift between the dark dark dark Amisian satire that simply can’t exist in the no-nonsense film. (But the one time a line from the book slips into the film is when Rudolph tells his wife his thought about how long it would take to gas everyone during a ballroom reception.)

In the book, a typical Amis plot of love-lies-blood takes shape around Thomsen, the first pov of each chapter, who’s infatuated with Hannah, which Paul finds out about. So, Paul threatens to kill Szmul’s wife if Szmul (a Sonderkommando responsible for carting the dead-dying around as well as welcoming those disembarking the trains) doesn’t kill Hannah. This absurd family melodrama takes place on literally the other side of the Shoah, which thematically resembles the film’s determination to place the viewer in the same space knowing full well what’s happening over there. The film, less plot-driven and more vibes-based, is simply about Rudolph’s transfer to Berlin, which temporarily separates him from his wife, the self-congratulated Queen of Auschwitz, who can’t move away from her dream house. The even more banal story of the film pressed film critics into uncritically evoking Hannah Arendt’s signature ‘Banality of Evil’ subtitle, which Glazer, as he mentioned, was conscious of in making the film. But like Arendt falling for Eichmann’s performance on trial and subsequent misnomer, The Zone of Interest depicts that evil sideways through smells (book) and sound (film) that is anything but banal.

Amis wrote his first Holocaust novel, Time’s Arrow, which is told in reverse death-to-birth chronology about an Auschwitz doctor—meaning, this person believed he was creating a race of humans and healing illness en masse—a quarter-century before Zone, but felt he had unfinished business on a theme he was uniquely qualified to write, even though he found that the facts ‘remain in some sense unbelievable, or beyond belief, and cannot quite be assimilated.’ And when he found his ‘negative eureka’ from the submission ‘that part of the exceptionalism of the Third Reich lies in its unyieldingness, the electric severity it with which it repels our contact and our grip,’ he also came across a new translation of Primo Levi’s The Truce, who argued that ‘perhaps one cannot, what is more one must not, understand what happened, because to understand is almost to justify.’ Thus, book and film linger on the quotidian without ever facing violence head-on, as Holocaust stories tend to do, to understand how, not why, the Nazis did what they did. This imposes a kind of Hemingway Iceberg to emerge, which hides the hideousness under the surface for our subconscious to grotesquely conjure through character perspective.

Regarding Glazer’s approach to adapting the satire, he hacks it away like a Kubrick adaptation to reveal the juice of what Amis conveyed. Both author and filmmaker constrict the grandiosity of humanity’s zero hour into the direct embodiment of perpetrator—one of us, one of us, we accept you, we accept you—and raise the uncomfortable truth of how any one of us could have been capable of these actions. This incomprehensible phenomenon can’t be reduced to understanding but it could be possible to have others witness through satirical representation, revealing the impossible as reality. Both provide a pov of the perps, but Glazer explicitly makes it come from the Zone itself rather than the characters. His hyper-objectivity—as he calls it: the stripping away of ‘screen psychology… that cinema fetishizes, glamorizes, empowers’—is filmed with scared-stiff frozen nightmare aesthetic tints, as if one’s eyes are adjusting to blinding sunlight after prolonged darkness. The screen fades-to-red, breaks the 180 degree rule many times, has thermal photography inserts of a townsgirl placing apples/pears for slave laborers, and contains hundreds of visual effects (smoke, ashy rain, etc.) strategically placed around the borders.

Whereas Amis provides a multi-dozen list of smells and putrid images through olfaction, Glazer introduces a double film through the sound. The film’s picture is entirely Apollonian (harmonious, ordered, perfectly Aryan) while the sound is Dionysian (dark, chthonic, chaotic) in extremis. The sound, which earned an Oscar for sound designer Johnnie Burn, along with The Shiningesque music by Mica Levi, conspire in shrill-shrieking riffs that always remind one of the Terror of where one is. You hear crackling and cranking and creaking, machines rattling and belching and incinerating, people yelling, shrieking, running (and failing), expiring, gargling, while the air is hissing and sooting ashes of flakey flecks of human. One of the most arresting moments is realizing that you, the viewer, will zone out these sounds after a short while, though they’re always dyingly faint over there, as the commandant and family and underlings would have done. Grandma leaves via Irish goodbye when she’s awoken by these sounds after spending a lovely day in the prim garden of her daughter and grandchildren.

Stanley Kubrick’s biggest unrealized project, after Napoleon, was a film on the Holocaust. Unlike the French dictator, who had a film about him flop while Kubrick was in prep, the director of Dr. Strangelove couldn’t find an angle on portraying something so strikingly horrific; making such a film depicting that reality is impossible and would dehumanize everyone involved. Whether conscious of his own satirical depiction of a nuclear holocaust or not, that kind of absurd satire was how Amis found his way around the camp walls, looking at the bourgeois lives rather than the airthful misery commonly found in depictions of this zone of interest.

Location, therefore, is important: what, or where, is the zone of interest? For Amis the novelist, the title is a triple entendre. First, it’s what the Nazis referred to as the greater Auschwitz area, camps and cities and killing fields; the ‘interest’ specifically referring to the money made by IG Farben, Siemens, and other proud German companies employing slave laborers while their families were gassed/burned next door. Second, in a more Holo-clichéd manner, it’s the place of atrocity where one finds out ‘who somebody really was. That was the Zone of Interest.’ Third, it’s how he, Amis, feels about the whole subject itself; from the magnitude and explicitness of the crimes, it’s simply above explanation.

Glazer, inspired by Amis’s book but departing wide, found relevance in the story to the politics of today. James Wilson, the film’s producer, said Glazer wanted the film to feel made for the present, a ‘present-tenseness’ and ‘selective empathy’ that provides a ‘thinking space’ for the viewers to lean into identifying with the commandant’s family. He argues that Holocaust films too often depict the differences rather than the similarities, which puts the atrocity into an apolitical box of the exception to reality. Glazer, during his acceptance speech for best international film at the Oscars, and Wilson, during his acceptance speech at the BAFTAs, directly called out how the construction of these walls today, which block out what’s happening on the other side and shows how we care about some groups of people more than others. Whether it’s the innocent people dying in Gaza and Yemen or in Mariupol and Israel (and the Auschwitz KZ eighty years ago), we shouldn’t ignore the walls separating perpetrators from victims.

The endings feature a meta-representation of depicting the Holocaust today. In the film, Rudolph heaves and throws up while descending a stairwell, looks towards the darkened hallway, and then cut to present-day janitors at the Auschwitz-cum-museum cleaning up and presenting the artifacts of organized genocide. Ending the film with a question, Glazer asks how we’re able to re-present these events from history while living with similarities today. Rudolph, after cutting back, looks on in horror then continues his descent. Was he having a moment, right after the ballroom party just before moving back to Auschwitz, where he could properly stop to reflect and think? In real life, explained by Amis in ‘Aftermath’, Rudolph was tried at Nuremberg, successfully, then wrote his auto-bio Commandant of Auschwitz while waiting in his death cell. His final words: “I have sinned gravely against humanity.” Was he already composing these words in Berlin, just before moving back to Auschwitz, in 1944, knowing full well for years that defeat was coming and their actions spectacularly judged by mankind through history? Anyone, including the so-called hardened Nazi, would shutter at that possibility of having to accept that they’re the freak—one of us—the deformed, immoral human.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t already done so.