Squaring the Drive-Away Dune Circlejerk, Weekly Reel #66

A throw-back Weekly Reel, with Jonathan Glazer, 'Rust' manslaughter conviction, megamerger antitrust enforcement, and reviews: 'Squaring the Circle', 'Drive-Away Dolls', and 'Dune: Part Two'.

Long time no see. The Weekly Reel experienced a delay for a while because of the Berlinale and State of the Film Union (and semi-failed 2023 catch-up film posts), but I’m back! But this time better than ever with a throwback to the pre-numbered Weekly Reel days of 2021/2, where I included film news and essay/article commentaries. Well now the old meets the new, where I revive those sections as well as retain the modern Watch Now, Save for Later, and Pass categories. This allows me to focus less on longer film reviews—therefore allowing me to write longer, standalone essay-like reviews (as with my recent one on The Zone of Interest)—and more on the developments in the film world. Enjoy, and please remember to share and, if you haven’t already, subscribe to receive these posts via e-mail, for free.

News:

Accepting the Oscar for best foreign film, Jonathan Glazer gave a short, well-worded and personal message against his “Jewishness and the Holocaust being hijacked by an occupation which has led to conflict for so many innocent people”. As usual, seen recently with the denunciation of Yuval Abraham’s acceptance speech at the Berlinale, pro-Israel mouthpieces save their most public outrage for Jewish artists denouncing Israel’s occupation and mass killing of Palestinian civilians. For Glazer, “450 Jewish creatives, executives and Hollywood professionals” signed an open letter condemning his speech, which, they claim, “gives credence to the modern blood libel that fuels a growing anti-Jewish hatred around the world, in the United States, and in Hollywood.” Perhaps if they actually listened to what Glazer said, especially in the context of what The Zone of Interest is about, then these non-A-list attention-seekers would understand how ironically stupid their argument is: wishing that a person who feels complicit in the killing of civilians stays silent. Even the official Auschwitz Memorial defended Glazer: “Critics who expected a clear political stance or a film solely about genocide did not grasp the depth of his message.” Always fun to watch how high the hypocrisy and moral projections will rise.

Overnight, an additional 500 Hollywood nobodies (i.e., people struggling to get projects made) looking for free publicity and moral pats on the back signed the letter. Nothing will ultimately come of this, which is all a distraction away from the killing of Palestinians.

Hannah Gutierrez Reed, the armorer on the film Rust, was convicted of involuntary manslaughter for being responsible in allowing Alec Baldwin to kill Halyna Hutchins, the cinematographer, and seriously injure the director, Joel Souza. She’ll receive up to eighteen months in prison. Alec Baldwin stands trial for manslaughter in July while assistant director Dave Halls, who handed Baldwin the loaded weapon without checking it, took a plea deal for a misdemeanor count of negligent handling of a gun and served six months of unsupervised probation. From the outset, Gutierrez Reed, an inexperienced armorer, was set up by the more protected filmmakers to take the L for their failures. Although her conviction serves as justice for Halyna Hutchins, the producers, including Baldwin as both producer and person who negligently fired a gun pointed at several people, will get away with hiring ill-equipped workers, mostly non-union, in a rushed workplace, who had many troubles with the production prior to the killing. It’s a very tragic story that many in Hollywood would like to brush under the rug because it highlights many of the industry’s illegal workarounds, that, when not adhered to, ends in disaster.

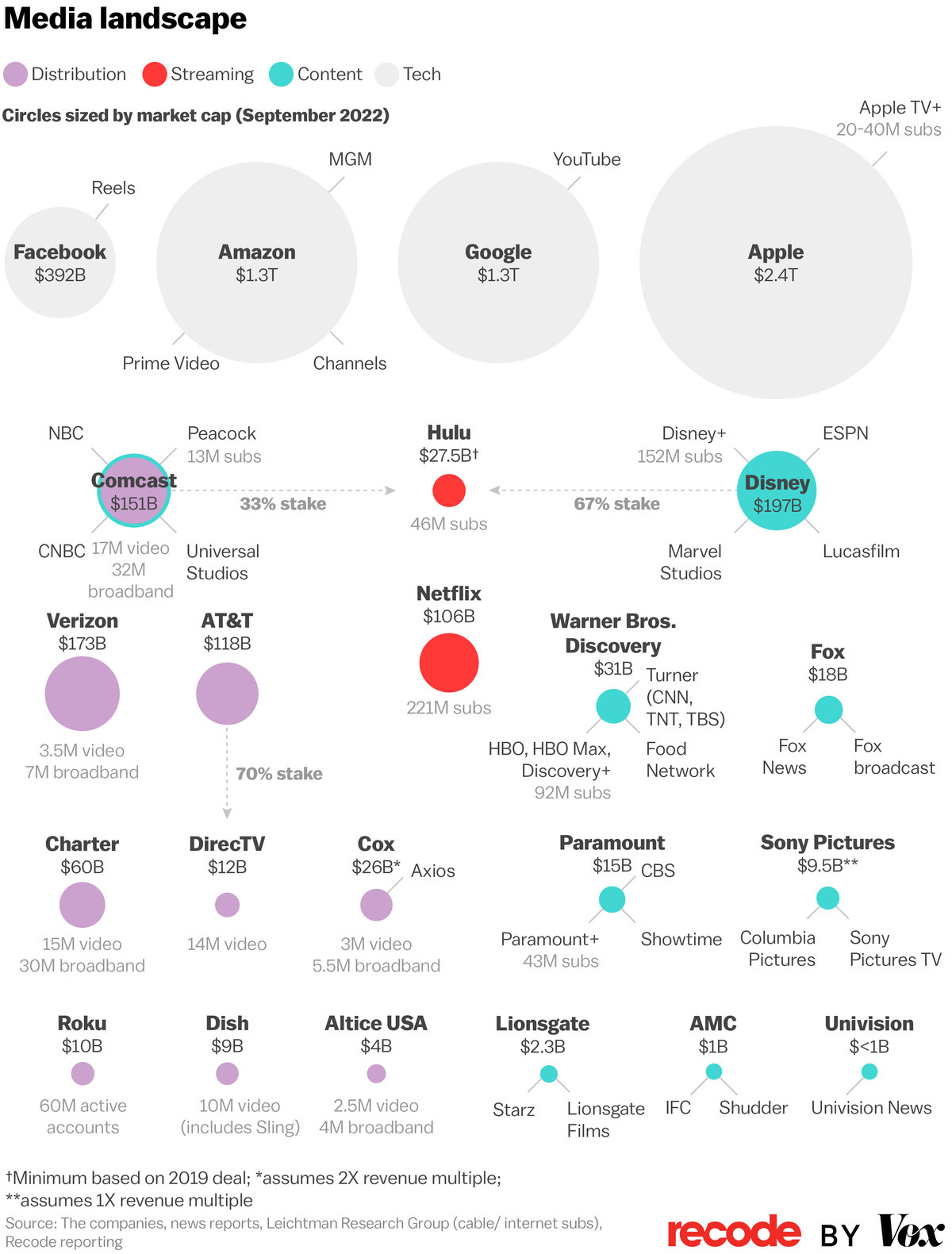

In the film industry, one finds matryoshka dolls everywhere when it comes to companies inside other companies inside other companies being bought, sold, spun-off, merged, liquidated, etc. When Disney bought 21st Century Fox several years ago, it did so to increase their content library to compete directly with Netflix at the beginning of the Streaming Wars (2019-2023). The acquisition took place because interest rates were low, Disney’s divisions were all breaking the bank, Wall Street favored both Disney’s profits and Netflix’s subscriber count, and Trump’s Justice Department wasn’t enforcing existing antitrust laws.

One of the little known details of the WGA strike last year was their dissatisfaction with mergers and acquisitions (M&As) lowering their working conditions through cynical MBA-pilled tax-incentivized maneuvering. Also, as a result of the end of the Streaming Wars, speculation about the selling of Paramount Global or Warner Bros. Discovery’s acquisitions of others, both recent M&A products themselves, has risen. But regulators are now paying attention to media conglomerates, with Federal Trade Commission chair Lina Khan zeroing in:

“We’ve seen over the last few decades significant consolidation and a wave of mergers and acquisitions, not all of which have ultimately served the American public,” Khan tells The Hollywood Reporter. “We’ve seen mergers that were allowed to go through that ended up consolidating power and resulting in higher prices, lower wages and quality, less innovation and just more stagnant markets.

“Generally speaking, TV and movies and entertainment are just such an important part of American cultural life, as well as our economic life,” the FTC chair adds, “so it’s an especially important area of the economy to get right.”

Gone are the days of rubber-stamping iffy megamergers that, some critics say, have allowed companies to suppress wages, engage in self-dealing via self-preferential agreements (think a studio giving a sweetheart deal to its network arm) and even shelve finished content for tax write-offs à la WBD’s handling of Batgirl and Coyote vs. Acme (Disney has done the same with unnamed titles). Hollywood may be better off for it, these observers contend. “I started working in TV during a time when you’d come up with a pitch and you actually had a marketplace to sell your concept to,” says Dan Gregor, a writer and producer on Chip ’n Dale: Rescue Rangers and How I Met Your Mother. “Now that the studios and networks are functionally the same, it’s almost always a take-it-or-leave-it offer.”

These issues became especially relevant last Summer, but also during the pandemic lockdowns, when film and TV production shut down for lengthy amounts of time, which revealed the cracks in the system: the workers weren’t paid and executives received bonuses. But when and how did this regulation begin?

The opening salvo from competition regulators came in 2021, when the Department of Justice antitrust division sued to block Penguin Random House’s $2.175 billion proposed acquisition of rival Simon & Schuster from Paramount Global in bid to crack down on so-called monopsonies, a dynamic in which a buyer with outsize market power can purchase labor and goods at prices under market value. Less than a year later, the Jonathan Kanter-led DOJ unit secured a major victory in the first successful merger challenge that went through a full trial in half a decade when a federal judge found that combining two of the world’s largest book publishers would hurt competition for best-selling books. Since around that time, the DOJ and FTC have successfully broken up deals in the airline, pharmaceutical and hospitality industries — securing guilty pleas in criminal monopolization cases along the way.

One need not be a hardened Marxist to understand that monopolies, and whatever names are used to obscure their reality, are bad and illegal. Importance of tech as well as vertical/horizontal mergers:

Amid this sea change in competition regulation, big tech — which aims to further encroach upon Hollywood with the rise of generative artificial intelligence tools — is bracing for a wave of antitrust rulings involving Apple, Meta, Google and MGM parent Amazon this year that could upend the traditional approach of growth through M&A.

Even in cases antitrust enforcers have lost, there is an argument to be made that they sent a message to the market and undercut prevailing theories around antitrust law that has largely protected tech giants. Before Khan and Kanter were appointed, regulators rarely questioned “vertical” transactions, which refers to mergers between firms that are not direct competitors, under the assumption they generally do not create monopolies. This thinking can be traced back to University of Chicago conservative economists and legal scholars Robert Bork and Richard Posner. Their work led to a wave of deregulation and the eventual elimination of the FCC’s “fin-syn” rules that blocked broadcast networks from owning primetime programming, which gave Paramount, Universal and Disney a roadmap to cement their market power by acquiring CBS, NBC and ABC, respectively.

But Disney acquiring Fox was certainly vertical, and an interesting caveat in the deal was that the Fox TV station had to be spun-off away from Disney for fears it would be too “horizontal” next to ABC and other Disney-owned TV channels.

With Khan and Kanter watching, M&A in the tech, media and telecom sector has slowed. In 2023, deals in the sector had a 46 percent close rate, a seven-point dip from the previous year, and a 30 percent fail rate, a seven-point uptick from 2022, according to an M&A review by financial software firm Datasite. This tracks with observations from dealmakers and analysts consulted by THR. “There are certainly deals people have looked at that they’re thinking harder about in light of the current antitrust environment,” says Jonathan Davis, a partner at Kirkland & Ellis. Potential enforcement has been “brought to the forefront of the list of threshold considerations” when companies assess deals, he adds.

…

The regulatory scrutiny runs headfirst into studio bosses’ instincts to chase growth through dealmaking. The 12-year period between 2009 and 2020 saw more than $400 billion in media and consumer telecommunications megamergers amid a wave of consolidation that killed thousands of jobs and blurred the separation of studios and distributors, giving rise to behemoths that control both the content production and distribution pipelines. Five transactions make up a bulk of that figure — Comcast and NBCUniversal (2011); AT&T and DirecTV (2015); AT&T and Time Warner (2018); Charter, Time Warner Cable and Bright House (2016); and Disney and Fox (2018).

Writer-producer Gregor says he had a movie at 20th Century Studios he was set to direct before the project fell into a “black hole” when Disney acquired 21st Century Fox. “Consolidation created a marketplace of creators who don’t have leverage to negotiate,” he says. Dozens of writers shared similar experiences with the FTC last year in support of revisions to merger guidelines that signal a tougher stance on vertical transactions and, for the first time, take into account a merger’s impact on workers. “Media consolidation has made it exponentially more difficult to sell a television or movie project,” wrote Leonard Dick, a writer for Lost and House. “If I am partnered with, say, 20th Television (owned by Disney) and the Disney-owned streamer/networks don’t want to order it, chances are slim to none another network/streamer will buy it because they want to own their own shows.”

Unless content is being licensed, which only Sony does en masse because it has no streaming service, media companies would rather sack their own projects they weren’t confident about rather than send it to a competitor. The worst and most public offender of this has been David Zaslav, CEO of Warner Bros. Discovery:

For signs that regulators may be saving the studio system from devouring itself, look no further than Warner Bros. Discovery, whose stock has lost more than 60 percent of its value since the merger was consummated. Cuts are the norm after a merger, but the way in which Zaslav pursued a plan to cut $3 billion in costs has drawn ire. By shelving nearly finished titles, including Batgirl, Scoob!: Holiday Haunt and Acme v. Coyote, the company saved millions of dollars that would have went to completing and the marketing the movies, on top of collecting hefty tax write-offs. In an industry that runs on relationships with talent, the decision from WBD execs, whose bonuses are tied to free cash flow and debt reduction, alienated some creators. The backlash has been sustained after each disclosure.

“Is it anticompetitive if one of the biggest movie studios in the world shuns the marketplace in order to use a tax loophole to write off an entire movie so they can more easily merge with one of the other biggest movie studios in the world?” Spider-Verse writer-producer Phil Lord wrote Feb. 9 on X of WBD, which drew calls last year from lawmakers for the DOJ to reassess its decision greenlighting the megamerger. “Cause it SEEMS anticompetitive,” Lord added.

It certainly does. Zaslav will receive his largest compensation package of all time very soon for his tax write-offs and helping extend the strikes long enough to not have to pay for productions.

One of the least talked about concerns with M&As is how it puts the movie studios alongside TV companies, book publishers, theme parks, merch stores, and, with tech giants, social media sites/apps, which is having the continuing effect of turning films into another piece of content. A single piece of the pie neatly packaged in subscriptions and deals, relying on the fickle availability it has on streamers, devalued into a commodity controlled by people who receive millions to rip you off. The worst aspect of M&As failing, which seems to be the trajectory, is that c-suites will enjoy the write-offs and bonuses while your subscription costs will increase and filmmakers will have precarious opportunities.

Watch Now

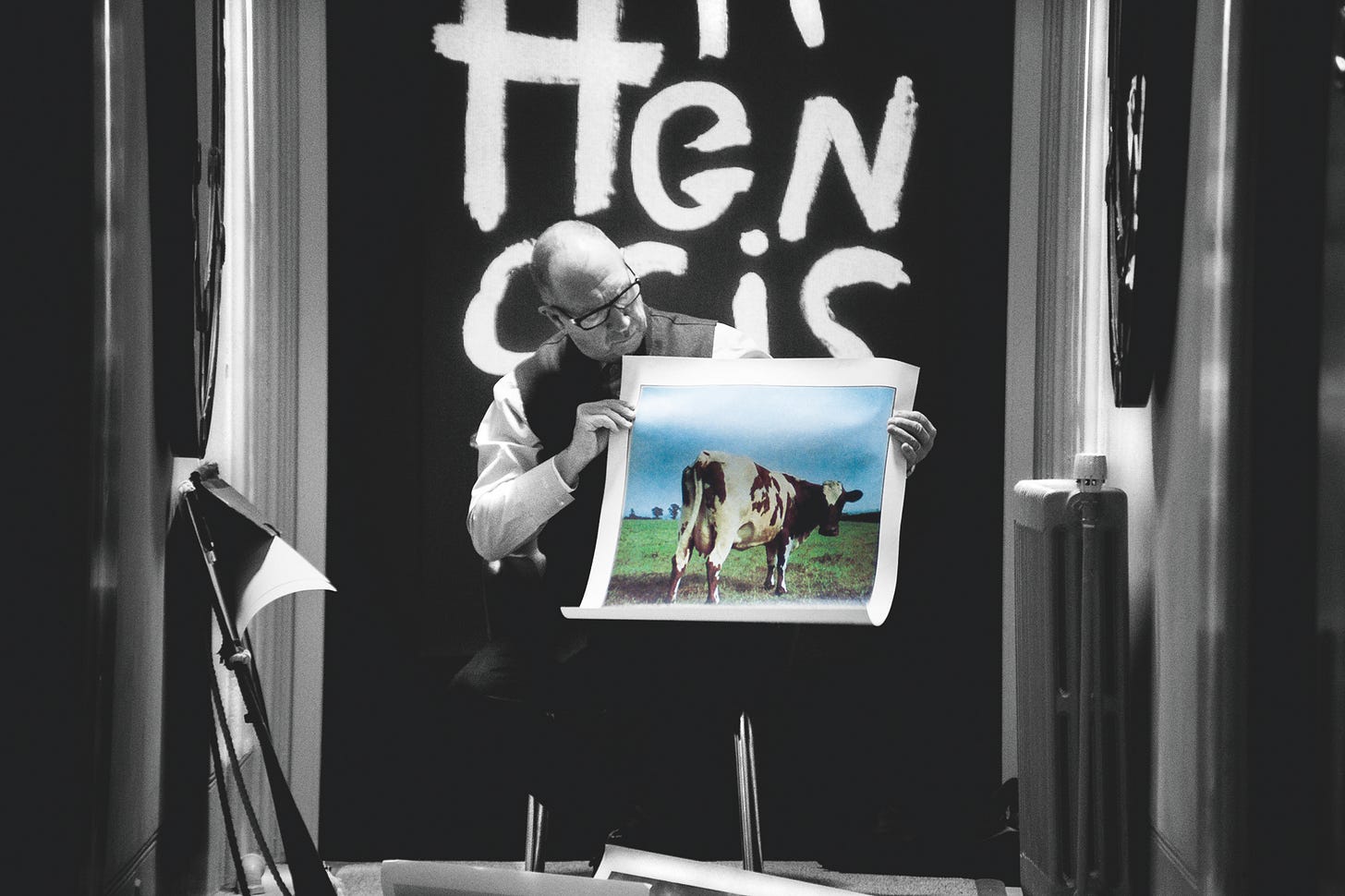

Squaring the Circle - The Story of Hipgnosis (2022, Anton Corbijn, UK)

Ever wonder who made Pink Floyd’s black prism for The Dark Side of the Moon, as well as the band’s burning man (who was actually a man set ablaze) on Wish You Were Here, and the cow’s backside for Atom Mother Heart, or the babies on the orange-red acid rocks of Led Zeppelin’s Houses of the Holy, or the Wings/Paul McCartney band on the run on the Band on the Run album, or Peter Gabriel in the driver’s seat of the rain-soaked blue car for his self-titled album? The graphic design/photography duo of Aubrey “Po” Powell and Storm Thorgerson formed Hipgnosis in 1967 based on the instantly iconic work they did for their mates, David Gilmour, Roger Waters, and Syd Barrett.

Aside from having one of the best prog and heavy rock soundtracks for a theatrical film, Squaring the Circle is a musical documentary with a fresh and unfussy style. It helps that the talking head interviews are classic rock Mount Rushmore figures not seeking to increase their own vanity, who are recalling the lesser known stories of their friends from sixty years ago that happened to create, often painstakingly and with great expense, the most iconic album designs of all time. Much of the original artwork and making of footage remain, which adds to the overall fun of watching an industry just before it became completely swallowed by music’s demotion to content.

On Netflix in the USA but in theaters in Germany and South Korea.

Save for Later

Drive-Away Dolls (2024, Ethan Coen, UK/USA) is Ethan’s first non-Coen bros. feature film—Joel had The Tragedy of Macbeth in 2021—which appropriately feels like half of a Coen Bros. film. It has all the typical macabre fun but is missing the meaty heft of story drama. (Macbeth has the heft but not the fun). Margaret Qualley and Geraldine Viswanathan star in this Henry James-adapted (originally titled Drive-Away Dykes) buddy-driving story where they overcome hurdles in their complicated relationship while involved in a cross-country wrong-car mix-up that leads straight to the top of Florida’s political class. The aesthetics are heavy on lesbianism, dildos, pink, male heavyweight actor cameos, and Beanie Feldstein hulking out. It never reaches the level of The Big Lebowski or Burn After Reading in its classic funny-death sequences or mistaken objects in briefcases, but its fun, it holds its own (people need to seriously chill with their Coen expectations), and ends before reaching too far past its britches.

In theaters, but probably for a very short amount of time.

Pass

Dune: Part Two (2024, Denis Villeneuve, USA) isn’t something I wanted to write about simply because I didn’t want to re-engage with how boring and unfocused and outright dumb so many things in this film are in relation to the praise it’s receiving. It’s the old I’m not sure if everything else is crazy or just me feeling. I didn’t like the first one as well, but would have welcomed its simplicity of time and location in the second. The score by Hansi is excellent, but seems to be from another film, one with more positive triumphs and good winning over evil beats. The other millennial A-listers are given less than nothing to work with and Timothée Chalamet isn’t meant to play action/sci-fi/adventure heroes. Florence Pugh’s only interesting moments were entirely about her headdress and Austin Butler is going to have a Stellen Skarsgård affectation for the next two years. The plot and story is in complete ruins by the second half. Rebecca Ferguson, bless her, tries her best. Christopher Walken? Why is Léa Seydoux in this? Anya Taylor-Joy had one of the dumbest out of place cameos since Taylor Swift in Amsterdam. It’s mid-March release will be interesting when the awards season fires up in the Fall because many, if not all, of these actors will be promoting their non-commercial, auteur stuff. Also, there will be a third film so this will fade away à la The Two Towers.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t already done so.